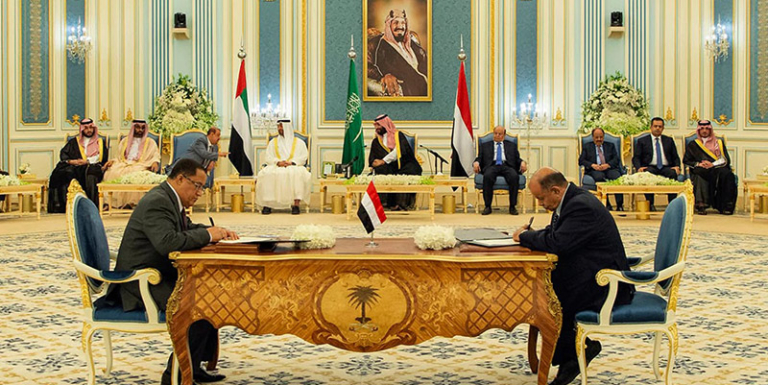

Despite claims to the contrary and references in the document to a comprehensive peace, the second version of the Riyadh Agreement (now dubbed an implementation mechanism) that was recently signed by Yemeni President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) does not change the status of forces on the ground in southern Yemen. Nor does it produce harmony between the two sides, let alone improve the chances of comprehensive peace in the country. Despite stipulating that all armed forces will be subject to the authority of the ministry of defense, current tensions, accusations, and clashes indicate that the ongoing conflict between the Hadi government and the STC continues unabated.

Despite initial optimism after the signing of the Riyadh Agreement in December 2019, and again after the signing of the implementation mechanism, the main provisions of the agreement remain unfulfilled. Implementation was supposed to be phased gradually, starting with halting the media wars then stopping the actual fighting on the ground and finally merging politically into a unity government. Militarily, the STC forces were supposed to be subsumed under the Hadi government’s ministry of defense and both STC and Hadi forces were supposed to leave Aden—a strange provision since Hadi’s troops were not in Aden but fighting their way toward it from the neighboring governorate of Abyan. These opposing groups remain engaged in occasional battles at the city limits of Abyan and Aden. Yemeni Prime Minister Maeen Abdulmalik Saeed was supposed to come back to work in his offices in Aden within a week of the signing, and a new cabinet formed within 30 days. There has been no progress on facilitating the travel of Hadi’s ministers to Aden nor on the formation of a unity government.

Hadi and the Legitimacy Government

Little love has been lost between Hadi’s government and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) which, among other irritants, hosts Ahmed Saleh, the late president Ali Abdullah Saleh’s son who is viewed by some as the heir to his father’s post. When the agreement was signed in Riyadh, many Hadi supporters used social media and interviews to voice their dissatisfaction and their suspicions about UAE intentions.

Little love has been lost between Hadi’s government and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) which, among other irritants, hosts Ahmed Saleh, the late president Ali Abdullah Saleh’s son who is viewed by some as the heir to his father’s post.

The provision that cabinet positions in the new unity government should be apportioned equally between northerners and southerners pleases the STC but it leaves Hadi chafing, since this ties his hands and diminishes his overall control of his government. Notwithstanding Hadi’s general reluctance to give away cabinet positions to forces he does not control, he has been ejected from Aden on several occasions, the last of which was the STC’s takeover of the city in April 2020, mere months after the signing of the Riyadh Agreement. The recent handover of Socotra to STC forces reinforces the perception among Hadi’s supporters that regardless of agreements signed, the STC will not relinquish effective control of any part of the south they currently dominate.

On the Southern Front

If Hadi has had trouble finding support in the south of Yemen, the STC itself also has not been met with universal acceptance as the representative of the entire south, with some factions in the southern Hirak (secessionist movement) voicing objections to the STC being in charge of doling out the southern cabinet posts decreed by the Riyadh Agreement. Some southern critics are also objecting to what they see as the STC giving up on the ultimate goal of southern independence by at least verbally agreeing to forsake the idea of self-administration. For example, Hassan Baoum, head of the southern Hirak movement that is seen as allied with (but not under the sway of) the STC, was critical of the Riyadh Agreement for falling short of answering the needs and achieving the aspirations of the people of the south—a euphemism for a separate state in south Yemen.

Even within the STC, there are differing views on the value of the agreement, with one prominent figure, Ahmed Okeil,1 saying that there is no trust in an agreement whose patrons do not have leverage over whether or not it gets implemented. This is a reference to other southern reactions to the agreement that have been laced with accusations that the “Qatar/Muslim Brotherhood faction” within the Hadi government was behind delaying its implementation.

Many in the south have long perceived a Muslim Brotherhood dominance, especially on the military side, over the forces that dominated the south under the late president Saleh’s regime and that are now fighting to wrest away the STC’s control of southern cities and governorates.

Many in the south have long perceived a Muslim Brotherhood dominance, especially on the military side, over the forces that dominated the south under the late president Saleh’s regime and that are now fighting to wrest away the STC’s control of southern cities and governorates. The STC military commander Mohsen al-Wali2 says that “The south is our land.We will either be its masters or become martyrs on its soil.” Such statements after the Riyadh Agreement and its implementation mechanism were signed indicate that deep mistrust continues to prevail between the two sides.

In the meantime, STC statements already show that the appointment of a governor, Ahmed Hamed Lamles, to “the capital” Aden alongside the new security chief, Mohammed Ahmed al-Hamdi, means that the Riyadh Agreement is lopsided in favor of the STC. It also lends credence to the theory that the Arab coalition intended to simply confer legitimacy to southern leadership and, eventually, independence. If the agreement goes through, Aidarous al-Zubaidi, the president of the STC, can then claim to be representing Hadi and go ahead and rule an independent south using that fig leaf as a cover.

All is not well, however, for the STC with southern citizens at large who, despite having a general sympathy for self-government, are not necessarily happy with the way their cities are being administered. The dearth of basic services has been exacerbated lately with floods and bad weather. Protests3 continue in Aden and elsewhere for lack of pay; armed forces of the south, for example, demonstrated in front of the Arab Coalition headquarters.

The Regional Factor

Hadi has not fared very well in Riyadh; rumors abound that his hosts have reached the end of their patience with him—or possibly have exhausted what usefulness he has had for them over the past five years and are now thinking of replacing him. The reason for this change of heart could be because Hadi has been an ineffective leader, unsuccessful at uniting the country behind him and therefore failing militarily against the Houthis. This could also be explained as part of the ongoing and complex dynamic between the UAE and Saudi Arabia, or more specifically the reported influence of Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed (MbZ) on Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS), the former having been extremely wary of the Muslim Brotherhood from the start and possibly demanding a change of leadership as a price for his continuing to support the war effort in Yemen. According to this theory, when the time comes, Hadi (who is not himself a member of the Muslim Brotherhood) and his vice president, Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar (who is), would both go. The real question is, would the departure of these two make any difference—positive or negative—on the course of the war in Yemen?

The UAE and Saudi Arabia united to defend their mutual interests starting in 2011 against what they perceived as a dangerous uprising, fearing the ensuing chaos could spread to their countries or worse, that the Brotherhood might take over the entire region.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia united to defend their mutual interests starting in 2011 against what they perceived as a dangerous uprising, fearing the ensuing chaos could spread to their countries or worse, that the Brotherhood might take over the entire region. The key difference where Yemen is concerned is that Saudi Arabia, unlike the UAE, has a deep-rooted interest in Yemen and in relationships across the political and tribal spectrum there. This has brought it close to some elements, like Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, who has served their interests militarily but who is considered a dangerous man by MbZ. However, the collaboration and close personal ties between MbS and MbZ may be tilting the former toward the vision of the latter, particularly as Saudi Arabia’s financial woes multiply and leave MbS with fewer resources to devote to the war on his southern border.

The Trump Factor

If the Riyadh Agreement itself did not state it so bluntly, US expressions of support—at least in official and conservative circles—blurted out optimism that this agreement strengthens the anti-Houthi side in the war. In a statement of praise for the Riyadh Agreement, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said “it’s a way of strengthening the alliance against the Houthis.” The Wall Street Journal, echoing this official position, stated in an editorial essentially the same sentiment: “This matters because it puts the U.S. and its Gulf allies in a better position to handle the Houthis, the Iran-backed group….” That this optimism has not yet been borne out with positive results on the ground has not, to date, troubled the Trump Administration enough to put its diplomatic weight behind an effort toward comprehensive peace.

Last year, reports emerged of a back channel from the US Department of State to the Houthis to explore means of finding a solution to the conflict in Yemen. A visit by David Hale to Riyadh in the same year was intended to energize peace talks, with the message to Riyadh and to President Hadi that the conflict must have a peaceful end. This was reminiscent of the late effort by former Secretary of State John Kerry to Oman (one of his last official visits in this position). Outside of such visits however, the thrust by two successive US administrations has been to side with the Saudis and to support their narrative that their military intervention in Yemen is part of a mission they share with the United States: to deny victory to Iran. Secretary Pompeo was again labeling the Houthis as tools in the hands of Iran, as follows: “If you truly care about Yemeni lives, you’d support the Saudi-led effort to prevent Yemen from turning into a puppet state of the corrupt, brutish Islamic Republic of Iran.” Such statements indicate a very hard line on Yemen that is not at all respectful of the nuances and internal dynamics in the country.

President Hadi,4 who has not shown effective leadership in general, repeats the same message in all his statements: that the UN Security Council Resolution 2216 must be the be basis for any solution and that the Houthi/Iran axis must be defeated. Repeating the main government’s negotiating position and railing against the Houthis are not effective ways of healing the wounds and reaching out to his enemies—something he has rarely done since the conflict broke out in 2014. As he urges the STC to implement the provisions of the agreement, Hadi stresses in the same statement the need to confront “the Houthi-Iranian project in Yemen.”

When It Rains, It Pours

Yemen today faces multiple scourges. War continues to take its human toll, mostly on innocent civilians; fighting in the south may have grabbed the headlines lately, but fighting on other fronts persists in the west—in Taiz and Hodeida—and along the Yemen-Saudi border. The Arab coalition continues its bombardment of areas controlled by the Houthis, particularly in (but not limited to) areas where they have recently advanced, such as in Marib.

Famine has continued to take its toll on Yemenis in general, but photos of emaciated children are particularly hard to take. COVID-19 is now widespread and there is not even proper accounting, let alone treatment facilities. Available data put the number of cases at nearly 1,900 and deaths at over 500, as of August 16. Add to all that the aftermath of last April’s floods and heavy rains that swept away parts of Aden, Sanaa, and villages in Hadramawt governorate. Waiting in the wings is the potential catastrophe that might well befall Yemenis and others in the region if the FSO Safer oil tanker in the Red Sea that is carrying 1.1 million barrels of oil off the shore of Hodeida is not dealt with properly.

Meanwhile, indirect talks on implementing the Riyadh Agreement between Hadi and the STC are mediated by Saudi officials. President Hadi headed to the United States for medical treatment and this will throw further doubt about the process. In his absence, Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar presides and may have to officiate at the inauguration of any new cabinet that emerges, should Hadi’s absence be prolonged. Amidst all these problems and uncertainties, it is likely that none of those involved in ongoing discussions in Riyadh may feel sufficiently empowered to make any significant concessions.

1 Source is in Arabic.

2 Source is in Arabic.

3 Source is in Arabic.

4 Source is in Arabic.