As it celebrates its 40th anniversary, the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) is facing a perfect storm of domestic, regional, and global security threats. Indeed, on February 13, just two days after that anniversary, a Sunni militant group killed 27 Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) soldiers in the southeastern province of Sistan-Baluchistan. In Warsaw, the Trump Administration co-hosted a security conference with Poland whose barely disguised goal was to mobilize European, Arab, and other states against Iran.

Iran’s leaders believe that both events are part of a US campaign to topple their regime. This campaign, they argue, includes the administration’s efforts to shut down the Islamic Republic’s oil sales, its bid to sabotage the latter’s missiles program, and its supposed support for the 2018 street protests in Iranian cities. President Hassan Rouhani’s claim that the Trump Administration was responsible for the February 13 attack in fact increases the prospect for a major military confrontation between the United States and Iran—or more likely, between Iran and Israel.

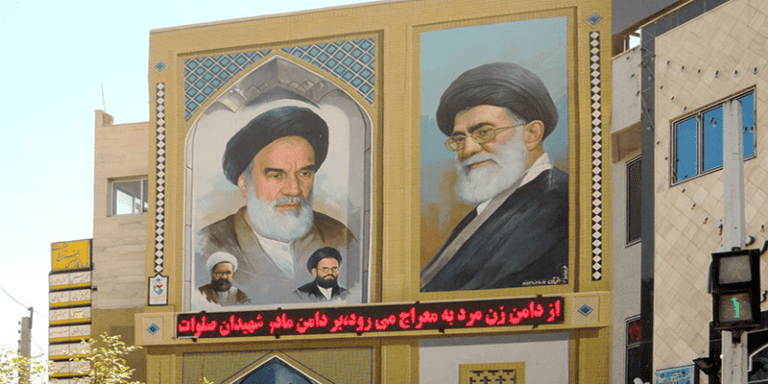

It might seem that the IRGC and its chief ally (and ultimate commander), Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, would welcome such a confrontation. After all, hard-liners view conflict with the United States as essential to sustaining the regime’s ruling ideology, a core feature of which is implacable hostility toward Washington. But Khamenei must tread carefully. As he advances in age (he is approaching 80), he must consider how his actions domestically and internationally will affect the inevitable succession struggle to come, and thus the authority of the very office he will bequeath to his successor.

Khamenei must consider how his actions domestically and internationally will affect the inevitable succession struggle to come, and thus the authority of the very office he will bequeath to his successor.

That struggle will be waged not merely over who replaces Khamenei, but also over the place of the rahbar (leader) in the overall political system. Khamenei’s authority stems from his ability to manage two roles: he is the “ultimate arbiter” of rival factions and their clashing domestic and foreign policies, and he is also closely aligned with the IRGC, which stands ready to crush any challenge to him. Thus, Khamenei’s test is in how to tackle rising security threats without empowering the IRGC in ways that could weaken the long-term authority of the rahbar as the ultimate arbiter in the system. The choices he makes today will influence the succession, thus shaping Iran’s domestic, regional, and foreign policies for many years to come.

The Rahbar as Supreme Political Leader

Since the country’s earliest days in 1979, Iran’s leaders have struggled to institutionalize the revolution while fostering an ideology of constant mobilization against presumed domestic, regional, and foreign threats. Even the IRI’s founding father and leading symbol of revolutionary action, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, struggled endlessly to stabilize state institutions—including his own office––to ensure that they would outlive him. He did this by creating a paramount office that fused the political position of rahbar with the position of ultimate religious authority known as the faqih or marjaa (ultimate religious source of emulation). Moreover, in January 1988 he declared that government is paramount, even over prayers. Government can also determine what is beneficial for people and the country. Invoking the term maslaha, or public interest, Khomeini thus held that religious authority had to be subordinated to the exigencies of power and politics.

Succession Struggles I

Khomeini’s fatwa (authoritative ruling) did not clarify which institutions have the authority to define public interest, and this helped set the stage for a fierce factional struggle over how to translate his wishes into action. Led by Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who served as president from 1989 to 1997, the neo-republicans favored a rahbar who would have sufficient political skills to manage factional competition in ways that would protect elected bodies such as the majlis (parliament). Thus, the leader would be an ultimate arbiter of the political field rather than the supreme power. By contrast, the supremacists wanted someone who would have uncontested power and who would use this power to favor non-elected bodies such as the Council of Guardians and the IRGC itself.

Rafsanjani tried to advance his case by selectively invoking Khomeini’s own words to argue that elected institutions such as the majlis and the president should play a leading role in defining “public interests.” Moreover, he pushed for then President Ali Khamenei to become the rahbar. Rafsanjani seems to have calculated that Khamenei would be politically pliable, particularly since apart from his evident lack of personal charisma, he had modest religious credentials: Khamenei was only a hujjat al-Islam, a middle ranking religious scholar. Seeking to smooth his path, Rafsanjani and his allies in the neo-republican camp secured an amendment to the constitution that dropped the requirement that the rahbar be a marjaa. This prioritization of political authority was underscored by Article 109, which stated that the qualification for being rahbar was possessing “more efficacious political and jurisprudential insight.”

Khamenei Aligns with the IRGC

Rafanjani’s effort to secure a pliable rahbar boomeranged. While he had argued that the leader’s political authority should be delegated to, or at least shared with, the elected majlis and the president, Khamenei sought to centralize power in the hands and office of the leader, known as the “abode of the rahbar.” Paradoxically, the 1989 amended constitution—which Rafsanjani hoped would serve the neo-republicans—in fact reinforced Khamenei’s clout. It did so by eliminating the position of prime minister and, even more, by assigning additional political and military powers to the rahbar. Khamenei used these powers to vastly increase the economic, coercive, institutional, and legal reach of his office. By the mid-nineties, the abode of the rahbar boasted its own intelligence services, not to mention control over the semi-state bonyads, or foundations. To reinforce his power, Khamenei forged a close alliance with the IRGC. The latter’s ample coercive and economic resources ensured that any bid to contest the leader’s authority would be crushed.

The leader/IRGC alliance received a further boost when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected president in 2005. Ahmadinejad put IRGC cadres into key positions in the cabinet and then revved up the regime’s effort to silence the reformists.

The leader/IRGC alliance received a further boost when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected president in 2005. Ahmadinejad put IRGC cadres into key positions in the cabinet and then revved up the regime’s effort to silence the reformists. This campaign came to a head during the 2009 presidential elections, when the security forces repressed the massive Tehran protests that erupted after reformists accused Ahmadinejad of electoral fraud. In a fiery sermon, Rafsanjani denounced the clampdown and indirectly assailed Khamenei. Stung by that attack, not to mention the massive street protests, Khamenei and his allies in the IRGC tried to push out all mainstream dissident voices from the political system in the ensuing years.

Rouhani Opens an Unexpected Door for Khamenei

Rouhani’s election in 2013 raised hopes that he and his reformist allies would reassert influence. But this very prospect also raised two critical questions. First, how would the rahbar work with an elected president whose popularity might pose a challenge to the leader’s own authority? Second, how would Khamenei’s alliance with and dependence on the IRGC affect his effort to work with Rouhani? The IRGC’s resolve to protect that special relationship, not to mention its hostility toward the reformists, suggested that the IRGC had every reason to sabotage cooperation between the two executives.

Yet in point of fact, by 2013 the economic and political terrain had shifted in ways that gave the leader a compelling interest to cooperate with Rouhani. Suffering under the weight of punishing economic sanctions, Khamenei needed Rouhani and his energetic, US-educated foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, to secure a nuclear deal that would reopen Iran’s economy to the world. But the logic of cooperation transcended economic considerations. Rouhani’s election facilitated a rebalancing of a system that had become dangerously polarized. This dynamic had rendered Khamenei dependent on one hard-line faction that was widely hated. A reopening of that political arena might help Khamenei reduce his isolation and, in so doing, manage factional struggles in ways that would not only help him reclaim some measure of authority as the ultimate arbiter, but also defend the institutional primacy of his office.

Rouhani’s election facilitated a rebalancing of a system that had become dangerously polarized. This dynamic had rendered Khamenei dependent on one hard-line faction that was widely hated. A reopening of that political arena might help Khamenei reduce his isolation.

Thus it was hardly surprising that Khamenei backed Rouhani by warning the IRGC against “interference” in the 2016 majlis elections (in which reformists took a sizeable number of seats, including Tehran’s 30.. Rouhani returned the favor by maintaining a cabinet that, to the consternation of reformists, included prominent hard-liners who had the support of the IRGC. In addition, he emphasized much needed economic reforms over political reforms that hard-liners opposed. Thus, the table was set for a recalibration of Iran’s domestic politics in a way that might also enhance the leader’s declining legitimacy.

Succession Battle II in the Making

Rouhani’s bids to reopen Iran’s system have collapsed around him. This timing could not be worse. With the rahbar approaching the ripe age of 80, the country’s factional struggles will not only be fought in a playing field that favors the hard-liners, but they will also be waged with one eye on the issue of succession. This does not mean that every single battle will be directly tied to the succession issue. Since factional struggles shape the balance of power, no political leader can ignore the opportunities and challenges created by an increasingly powerful IRGC—or an isolated reformist movement that has less space to muster support for a leader who might favor more competitive politics.

The economic protests that began in the provinces and then spread across the country illustrate this point. The demonstrations were initially instigated by IRGC hard-liners in a bid to discredit Rouhani. He responded by echoing the leader’s call for national unity while assailing the IRGC’s economic privileges. But Rouhani’s tricky balancing act could not compensate for his lack of powerful domestic allies. Indeed, Rafsanjani’s sudden death on January 8, 2017—supposedly the result of a swimming accident—left Rouhani without the support of the very leader who had pushed him to run in 2013. Had Rafsanjani lived to witness Rouhani’s reelection in June 2017, he would have surely supported the beleaguered if resilient president. The fact that Rouhani openly called for an investigation into Rafsanjani’s suspicious demise demonstrates that he is very worried about the escalating dangers posed by the IRGC’s securitization of Iran’s domestic politics.

The fact that Rouhani openly called for an investigation into Rafsanjani’s suspicious demise demonstrates that he is very worried about the escalating dangers posed by the IRGC’s securitization of Iran’s domestic politics.

That dynamic also poses a complex challenge to Khamenei. He probably does not regret Rafsanajni’s passing. Indeed, Rafsanjani’s defiant speech following the 2009 clampdown raised a troubling prospect, namely that he would support a successor who advocated a more flexible approach to domestic and foreign policies. Such a prospect was not inconceivable given that Rafsanjani chaired the Council of Experts—a clerical body that was constitutionally mandated to choose the new rahbar. Rafsanjani had lost that position in 2011 to a long time Khamenei ally, Mohammed Reza Kani, which removed him from the small circle of clerics who would ultimately work the succession issue—a development that was made permanent by his untimely death. Freed from this meddlesome cleric, Khamenei must still contend with the imposing task of defending his office’s authority from any potential challenges posed by the IRGC.

In fact, Khamenei has taken steps to contain the IRGC. His warning that he would “confront” any force “tampering” in the June 2017 presidential election was clearly meant to deflect hard-liner efforts to block Rouhani’s reelection. The following year Khamenei issued an edict ordering the IRGC to reduce its role in the economy. One purpose of the edict may have been to placate protesters, some of whom hurled verbal assaults at the IRGC. Yet Khamenei was probably also trying to mollify business leaders who expected that the government would impede the IRGC’s growing role in the economy. That the IRGC largely ignored his ruling underscored the depth of its power and autonomy.

Khamenei has also tried to solidify an alliance with conservative clerics, some of whom will play a leading role in choosing the next leader—or may even be contenders for the office. These clerics include judiciary chief Sadeq Larijani, a dependable hard-liner from a powerful and wealthy family; however, Larijani also has drawbacks, including lingering accusations of corruption. Another ally and possible contender is Ebrahim Raisi, a relatively young 56-year-old who ran for president in 2017. Raisi brings two assets: he chairs the Astan Quds Razavi, the Muslim world’s wealthiest charity, and he has avoided factional fights. This profile makes him a good fit for assuming the role of chief arbiter in a system that will experience intensified factional conflict once Khamenei passes. But whether Raisi or any other candidate can fill this role and still contain the IRGC is far from clear.

The View from the Trump White House

The Trump Administration’s leading foreign policy officials insist that such factional battles in Iran merely mask a regime that is in fact united when it comes to its most vital domestic and foreign policies. But this judgment not only does an injustice to the many reformists who have been imprisoned for defending basic freedoms; it also obscures the key role that successive US administrations have played in fostering internal and regional threats that have strengthened the IRGC’s hand in ways that have impeded the reformers’ struggles to pursue peaceful, nonviolent change through—rather than against—the existing political system.

It would be premature to conclude that the IRGC is now stronger than the rahbar and thus destined to subordinate his authority to its whims and interests.

Still, it would be premature to conclude that the IRGC is now stronger than the rahbar and thus destined to subordinate his authority to its whims and interests. A “quiet coup” would completely upend the institutions that have sustained Iran for 40 years. But if a prolonged military conflict does in fact erupt between Iran and the United States, or Israel and Iran, IRGC leaders might be tempted to grab power to prevent a total collapse of the system. They would then jettison the Iran nuclear deal that Rouhani and the EU have struggled to sustain against great odds. The White House’s dream of regime collapse would then become a nightmare for which there would be no obvious solution—including war. Because political upheaval and state collapse often generate new security challenges for all parties concerned—including US friends in the Middle East—the administration must be careful what it wishes for.

This article went to press as news was reported of the resignation of Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif. President Hassan Rouhani has not accepted Zarif’s resignation yet.

Photo credit: David Stanley/Flickr