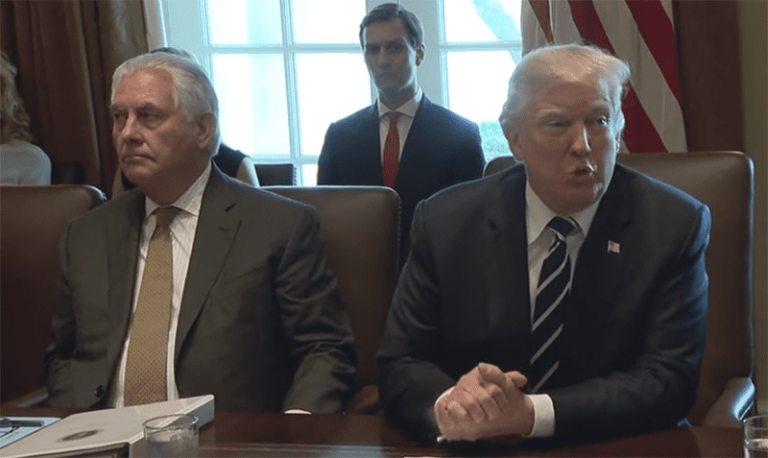

No secretary of state in modern American history has been as publicly undermined by a US president as much as Rex Tillerson by Donald Trump. The concern here is not only about the public persona of the secretary of state but also how the current administration views international relations and the role of US diplomacy in engaging the world. As the Trump Administration faces myriad global challenges, incapacitating the secretary of state risks taking the United States once again down the path of war.

Tillerson’s list of grievances against the White House is rather long and includes slashing the State Department budget, which undercuts his diplomatic efforts and marginalizes him in the national security team. In return, Tillerson has not always been acquiescent. He once pointed out that the president “speaks for himself,” has never flatly denied calling Trump “a moron,” and has reportedly had outbursts of temper during White House meetings. There has been a lot of speculation that Tillerson might be on his way out as well as a number of reports detailing how the State Department is in disarray. The crucial question is whether the ego clashes in the Trump-Tillerson era are a temporary trend or if they will have lasting impact on US global leadership.

Institutional and Personal Rivalries

The contempt the White House has for the State Department is rooted in US bureaucratic culture, most notably when a conservative Republican president is in the Oval Office. Secretary George Shultz spoke about a “sense of estrangement” and “guerilla warfare” with the White House under President Ronald Reagan. Secretary Colin Powell struggled for four years to make his voice heard because of his fundamental ideological differences with President George W. Bush’s team. While Secretary Hillary Clinton had a cordial relationship with President Barack Obama, she was sidelined by his niche of close advisors.

Indeed, such bureaucratic spats are not new. However, the dynamics under President Trump are unprecedented. Instead of the common rivalry between the offices of the secretary of state, the Pentagon, and the national security advisor, the three are now coordinating to rationalize President Trump’s sporadic foreign policy. Furthermore, rather than staying above the fray, as presidents typically do, Trump is initiating these tensions by publicly picking on his own principal advisors.

Tillerson, who is the first secretary of state without government and foreign policy experience, strived early on to define his role in the Trump Administration. He began his tenure in February with a few handicaps: a president who decided to cut the State Department’s budget, portfolio, and senior leadership; Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, opening back channels with foreign leaders; and the secretary of state excluded from White House summits with Trump’s counterparts. After having to fight his way through to the president’s inner circle, Tillerson found relief with the appointment of HR McMaster as national security advisor and John Kelly as White House chief of staff. The three generals (McMaster, Kelly, and Defense Secretary James Mattis) are helping Tillerson survive in Trump’s world, at least for now. During the White House briefing earlier in October, McMaster went out of his way to state that Tillerson “took a foundational role” in shaping US policy toward Iran.

The White House’s National Security Council, which took on an expansive foreign policy role under Obama, was downsized under Trump, yet the State Department did not benefit from that. The State Department’s traditional roles were either terminated due to budget cuts or transferred to the White House and the Pentagon.

Challenges Facing the Top US Diplomat

Every secretary of state, throughout modern US history, has faced three conflicting challenges: running a complex bureaucratic organization at the headquarters, travelling around the world on behalf of the United States, and managing institutional rivalries at home. Past secretaries of state usually succeeded in one at the expense of the others. Secretary Condoleezza Rice had the unique ability to influence President George W. Bush’s foreign policy, and Secretary Hillary Clinton’s added value was her brand name on the global stage. However, both fumbled in their roles as executives. While Powell was marginalized by the Bush team, he was beloved by career diplomats. Tillerson, however, is simultaneously struggling in all three challenges.

A State Department staff survey recently showed that employees are concerned about the lack of support from Tillerson and the Trump Administration. The current secretary of state is not effectively leading any major diplomatic crisis. He made only a few friends on Capitol Hill, at the State Department, and in the media. Tillerson, whose character has been widely dissected by others, has yet to correct the perception the public has of him. However, even if he claims all these skills that make him excel as secretary of state, it might not be enough. Even a towering character like Colin Powell failed to have an impact on the Bush doctrine and all his arguments did not prevent the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. This begs the question: can a secretary of state function without the president’s support?

History would answer in the negative. President Richard Nixon conspired with National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and kept Secretary of State William Rogers out of the loop on many international issues. Kissinger derided Rogers in his book, White House Years, saying that “few secretaries of state can have been selected because of their President’s confidence in their ignorance of foreign policy.” President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany without consulting his secretary of state, Robert Lansing, and had his own presidential envoy to conduct diplomatic relations with foreign leaders. One can argue that Trump may have chosen Tillerson to project his own control of foreign policy and is deliberately sidelining the State Department.

What Tillerson is most guilty of, however, is not adjusting to what Senator Bob Corker (R-Tennessee), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, famously described as the White House’s “adult day care center.” The president’s team reportedly had to school Trump on the benefits of global US presence and they often tailor policy arguments to his businessman’s understanding of foreign policy. Tillerson is also guilty of not being a yes-man or flattering the president’s ego. He failed to establish a rapport with the president, and Trump believed his secretary of state is not bold enough and, rather, represents the establishment.

While his popularity is low among his colleagues in Foggy Bottom, Tillerson has been playing the traditional role of defending the State Department’s internationalist views. If he resigns in the near future, and a new secretary of state more aligned with Trump’s policies replaces him, the dynamic may likely shift to infighting between the State Department and the Pentagon, or even inside the State Department itself.

How the World Views Washington

In Tillerson’s own words, Trump’s tweets are an “unknown” factor in shaping US foreign policy. He notes, “I wake up the next morning, the President’s got a tweet out there. So I think about, OK, that’s a new condition. How do I want to use that?” What is appalling about this statement is that the secretary of state considers public communications by the president as a directive instead of participating in shaping that policy behind closed doors. It also shows that the secretary of state not only has to address world crises but also to deal with whatever the president tweets at him. Clearly, the Trump Administration’s shortsighted approach is costing the United States its global standing.

Indeed, world leaders are getting accustomed to new norms in Washington and are interpreting the Trump Administration in three ways. There are those who do not take the US president seriously and are betting on the establishment—or what has become known as the “deep state”—to correct that path. There are those who see Washington as a divided place where no effective policy can emerge; hence, these leaders are adjusting to that new global reality. Finally, there are those who do not take Tillerson seriously and have established their own line of communication with Trump’s closest advisors.

Foreign diplomats have complained that the State Department is not returning their calls and world leaders are primarily using the Kushner connection or whomever they can spot in Trump’s circle. But no matter how world leaders are reading the Trump Administration, Washington’s role in managing crises abroad is diminishing: The crises of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), North Korea, Iran, and Kurdistan are just a few examples. The United States is either taking sides in these crises, instigating them, or staying aloof. The Trump Administration is not showing any intention to lead globally, which is resulting in an incremental paradigm shift in the international system.

If Tillerson Stays or Not, Will It Matter?

Trump and Tillerson seem to be two incompatible characters; even if Tillerson sticks around as secretary of state, repairing his relationship with the president is unlikely in the long term. The test for any secretary of state is the ability to have direct access to the president, and Tillerson has had plenty of face-to-face and sit-down time with the president; however, he has not earned the trust of the president he serves nor the career diplomats he leads. At the end of the day, the secretary of state cannot be effective without presidential support; therefore, the White House must address the Tillerson issue once and for all, either by enabling or replacing him.

What is also missing at the State Department is a new sense of purpose and a clear division of labor on foreign policy with the White House and the Pentagon. Tillerson and the State Department can no longer claim the exclusive mantle of foreign policy; the US Administration, and the world, are becoming increasingly complex.

The Tillerson problem has impact on the day-to-day operations of US diplomacy, yet replacing Tillerson will not solve the Trump problem. The US president, on the one hand, is giving a blank check to the Pentagon with no oversight and, on the other hand, is seizing every opportunity to undermine the State Department. Militarizing US foreign policy and undermining the secretary of state without offering a presidential doctrine are a recipe for making the world less safe.

Indeed, the most damaging impact on US foreign policy is inflicted by Trump himself. China and Germany are filling the void of the US global retreat, Russia continues to lead the way in the Middle East, and global confidence in Trump is at a 22 percent low, as surveyed by the Pew Research Center. US soft power, which was built by decades of persuasion and non-coercive tools, is no longer inspiring or persuasive. The political values and foreign policy the United States is projecting abroad are at odds with the international system Washington has shaped. That global perception about the US role might outlast the Trump presidency.