In just a few short weeks, the ground has shifted dramatically underneath US policy in the Middle East. The almost complete collapse of the Islamic State (IS) in Iraq and Syria, the fallout from the Kurdish independence referendum on September 25, and President Trump’s announcement of a new get-tough policy on Iran have shaken up regional politics significantly. The Trump Administration now faces the challenge of forging a new policy direction that can cope with these developments and keep the United States and its allies moving toward the goal of successfully confronting Iran’s regional ambitions while keeping the fight against IS on track.

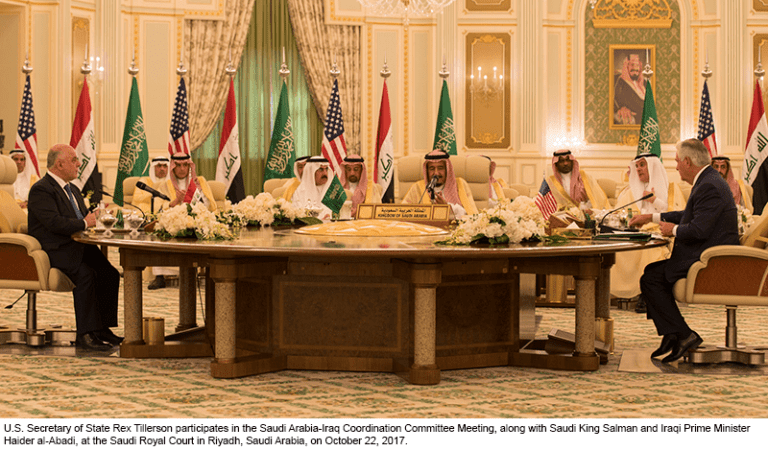

One key piece is the administration’s effort to bring about improved relations between Saudi Arabia and Iraq in an effort to contain Iranian influence in the Gulf. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s late October visit to Riyadh for the inaugural meeting of the Saudi Arabia-Iraq Coordination Council marked an important success in moving these two mutually suspicious and aggrieved countries toward a more productive political and economic relationship. But there are many potential pitfalls, and improved Saudi-Iraqi relations alone will not sufficiently bolster the twin imperatives of confronting Iran and ensuring a unified effort in the ongoing fight against IS. A broader US regional effort is needed.

Tillerson to Riyadh with Baghdad on His Mind

Tillerson’s recent trip to Riyadh is an interesting and potentially important first step. During his visit he attended the first meeting of the Saudi Arabia-Iraq Coordination Council, where he took the opportunity to begin fleshing out Trump’s new, more aggressive approach to Iran. He urged like-minded countries, especially those in Europe, to boycott business dealings with entities of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) to help prevent its efforts to “foment instability in the region.” Tillerson also demanded that Iranian militias fighting against IS in Iraq need to “go home and allow the Iraqi people to regain control.”

Tillerson’s remarks on the “Iranian” militias missed the mark, as many of the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) to which he evidently referred have ties to Iran but are not per se Iranian. His words also fell flat in Iraq, where he visited a few days later. (Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s office issued a terse statement rejecting Tillerson’s demand and calling militia members “patriots.”) But however coolly Tillerson’s comments on the PMF were received in Baghdad, they certainly made waves in Tehran. Official media outlets, including some associated with the IRGC, warned darkly of the threat posed by a looming “Arab-American” axis to confront Iran. They speculated that development and reconstruction assistance from the United States and Saudi Arabia would be leveraged to woo Iraq away from Iran and swing the outcome of the parliamentary and provincial elections set for next year.

The Iranians are not necessarily wrong in their assessment. As National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster said recently, the United States seeks “a stable Iraq, but a stable Iraq that is not aligned with Iran,” adding that Saudi Arabia can play a key role in achieving this and thus help to thwart Iran’s “hegemonic design.”

Tillerson, who has encouraged improvements in Saudi-Iraqi bilateral relations since his confirmation as Secretary of State in February, clearly agrees. At the joint press conference on October 22 with his Saudi counterpart, Adel al-Jubeir, Tillerson said that bolstering Saudi-Iraqi ties was essential to “counter some of the unproductive influences of Iran inside of Iraq.” He added that King Salman bin Abdulaziz strongly supports President Trump’s new strategy on Iran.

Riyadh Looks to Firm Relations with Iraq

Saudi Arabia recently has been working to put its relations with Iraq on firmer footing, realizing that while the government in Baghdad is not perfect, and Tehran is bound to retain substantial political, military, and economic influence in the country, Riyadh’s interests are better served by efforts to draw the Iraqi government closer and provide a counterweight to Tehran.

Examples of such efforts abound. The kingdom recently reestablished regular air connections between Saudi Arabia and Iraq, and the main border crossing at Arar has been reopened for trade and travel. Saudi Arabia plans to increase the number of Saudi consulates in the country, including presences in Najaf, Basra, and Mosul. Several ministerial-level visits have been exchanged with an eye toward expanding relations in a variety of areas; Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Energy, Industry, and Mineral Resources Khalid al-Falih, for example, traveled to Baghdad earlier this month to discuss economic ties and cooperation to support oil prices, noting that the two countries are “working on measures to speed up the establishment of an economic partnership and to reactivate cooperation and economic complementarity.” A joint trade commission was set up in early October. These latest moves build on a series of tentative measures undertaken by Saudi Arabia to improve relations with Iraq and key political figures since the reopening of its embassy in Baghdad in 2015.

Success is by no means assured, however. The history of Saudi efforts to strengthen ties to Iraq is problematic at best. Relations between the two countries suffered under the Saddam Hussein regime and nosedived following the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. The Saudis were against the invasion and horrified by its aftermath, during which Iran became more and more influential politically, economically, and militarily in Iraq. As a result, Riyadh tended to shun Iraqi Shia political leaders like former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, whom they considered an Iranian lackey, while supporting Sunni insurrectionists in their periodic struggles against the government. Neither of these tactics succeeded in reducing Iranian clout or boosting Saudi influence in Iraq. The ejection of the Saudi ambassador to Baghdad Thamer al-Sabhan in 2016 after injudicious criticisms of Iranian-backed militias only underscores the inherent tensions that still underlie the relationship.

Despite past Saudi missteps and limited influence in Iraq, the kingdom has two major cards to play. First is its willingness to reach out to Iraqi politicians who, despite maintaining relatively close ties to Tehran, are considered more Iraqi “nationalists” than Iranian partisans. One such political figure is Prime Minister Abadi, who sees advantage in some distance from Tehran and with whom the Saudis have shown a willingness to cooperate. Another, surprisingly, is the cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, an influential anti-American firebrand with deep ties to Tehran who has, nonetheless, displayed willingness to stand up for Iraqi national interests. Sadr visited Riyadh in July for talks with senior officials, including Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, one of the drivers behind the push to improve bilateral ties. The kingdom will remain open to meeting with other like-minded politicians; this may prove particularly important in the runup to national and provincial elections in 2018, where the Saudis will need allies and Iraqi politicians will need patrons.

Second, both the Saudis and Iraqis recognize that economic and commercial ties could prove profitable for their business communities while providing an important alternative to growing Iraqi economic reliance on Iran. Indeed, this is an area of real competitive advantage for Saudi Arabia, which has a per capita GDP about four times that of Iran. Revitalization of formerly robust trade relations between Saudi Arabia and neighboring Iraqi provinces such as Muthanna could be a driver of prosperity in much of Iraq’s south. This could also provide an avenue for greater influence in an area of the country where Iran is also seeking economic and political influence. Development of economic zones in border areas, as well as rejuvenation of transportation and commercial ties, could thus prove a major step in strengthening bonds between the two countries.

The Necessary Role of the United States

Without a sustained US policy push to help rebuild ties, however, the Iraqi-Saudi relationship may continue to suffer the type of setbacks both countries have come to expect. It is here that the United States faces particular challenges. The important task of strengthening Iraqi-Saudi relations cannot be a stand-alone effort but must be part of a broader regional strategy to reintegrate Iraq into the Arab region, resolve—or at least tamp down—bickering among US allies in the region, and work from there to keep pressure on IS and establish a coordinated strategy against Iran.

There are reasons to doubt this will happen. Since 2006, when US National Security Council staff first drafted a comprehensive regional strategy to push back against Iranian influence and hostile activities in Iraq, of which the reintegration of Iraq was a critical part, American diplomatic and military efforts in this regard have been lacking in consistency and focus. This was especially true during the Obama Administration, where the need to set the conditions for the US withdrawal in 2011 and subsequent diplomatic efforts to secure a nuclear deal with Iran helped push aside other concerns, including Iran’s malign activities and poor human rights record. Today, with intensifying political turmoil in Washington and severe disorganization, disaffection, and understaffing in the State Department, it is unclear if an effective diplomatic effort could be sustained.

But the administration has to try, and it should focus on three key lines of action. First, Washington should redouble its efforts to bring Saudi Arabia and Iraq closer and draw in the United Arab Emirates, which has launched its own efforts to improve ties with Baghdad. In addition, the United States should seek to involve Jordan, which has close links to Iraqi Sunnis and access to Anbar province, the key to Iraq’s Sunni heartland. Amman has limited resources and is overstretched by dealing with the fallout of the Syrian situation, especially massive inflows of refugees, but can play an important role as a political facilitator in support of US and Gulf efforts.

Second, the United States must try harder to effect a rapprochement between Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar. These three Gulf states have been locked in a bitter diplomatic standoff since June, ostensibly over Qatar’s alleged financing of terrorism and extremism but really concerning Riyadh’s anger over Doha’s independent-minded foreign policy direction. This dispute has complicated the Trump Administration’s efforts to push back on Iran and will vitiate the positive impacts of improving Saudi-Iraqi relations. Up to now, the contretemps has proved resistant to Tillerson’s efforts to broker a solution (he came up empty in his most recent visit to the Gulf). President Trump, who played a prominent role in stoking the crisis and undercutting Tillerson’s diplomatic efforts in the first place, should now make clear that the problem must be resolved and put his influence on the line to make it happen. Trump’s apparent willingness to host the parties for a meeting at Camp David for talks to end the crisis would be a useful step.

Finally, the administration cannot ignore the ongoing turmoil within Iraq itself, which harms Iraq’s ability to act as a reliable partner for the United States and the Gulf in the fight against IS and to establish more distance between the central government and Tehran. The negative fallout from the Kurdish independence referendum, which included the seizure of Kirkuk by government forces and PMF militias, has pushed Arab-Kurdish relations to a crisis point. It has also intensely roiled internal Kurdish politics, which was a significant factor in the decision to resign by the Kurdistan Regional Government’s president, Masoud Barzani. Moreover, the Kirkuk operation has provoked an outburst of anti-US rhetoric among the Kurds, many of whom felt the United States did too little to defend them.

Washington should move quickly to help restore calm, brokering talks between Kurdistan and the Abadi government to manage the immediate fallout and laying out a path for a broad-based approach that can resolve the major issues diplomatically. While assuring Kurds of Washington’s ongoing support and warning against additional military moves by the Iraqi government and its allies, the United States also has to dissuade Kurdish leaders from further unilateral steps and secure their commitment to negotiated solutions.

These measures will magnify the impact of US-backed efforts to strengthen Gulf-Iraqi cooperation. They will go a long way toward giving shape to the Iran strategy that Washington envisions and providing a stable platform for improved regional cooperation.