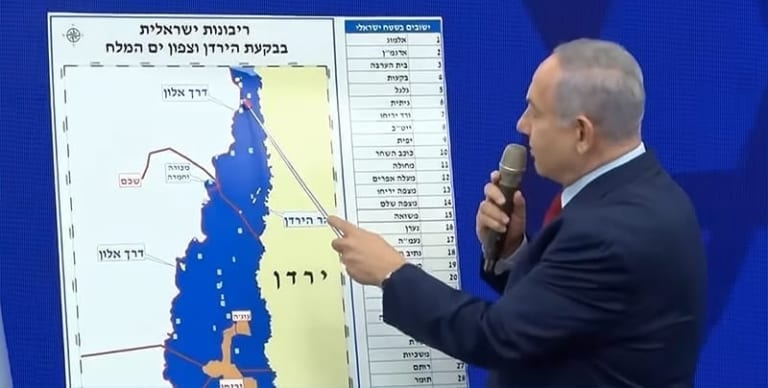

In the week leading up to the Israeli general election, Israeli Prime Minister and head of the Likud Party, Benjamin Netanyahu, made several promises to the voting public that, if re-elected, he will take steps toward annexing occupied Palestinian territory in the West Bank. Appearing at a podium for a televised address which he had dramatically announced earlier in the day, Netanyahu––who is famous for his use of props and stage gimmicks––used a map that depicted his plan. But this announcement is more significant than theatrics because it put a territorial outline on what had previously been a vague political promise. Netanyahu explained that in his plan Israel would formally annex the Jordan Valley in the occupied West Bank without taking in any Palestinians in the process. The largest Palestinian population center in that territory, the city of Jericho, was excluded from his annexation plan, practically becoming an enclave surrounded by Israeli annexed territory with access roads leading in and out.

Additionally, Netanyahu promised to annex the settlements in the West Bank, a desire he shares with the majority of settlers there, including Jewish settlements in the city of Hebron where a few thousand Israelis are embedded among hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who live under acute oppression of the Israeli military that has been charged with supporting the tiny number of Jewish fanatics occupying the center of the city there.

What is worth noting is Netanyahu’s avoidance of the language of annexation. Instead, he prefers to use formulations like “applying” or “extending” Israeli law to the territory.

What is worth noting is Netanyahu’s avoidance of the language of annexation. Instead, he prefers to use formulations like “applying” or “extending” Israeli law to the territory. This is important for a few reasons. First, the terminology suggests that the Israelis understand the negative optics of announcing the annexation of occupied territory, which would be an illegal move under international law that would draw condemnation from the international community. Second, using the term “annexation” may cast doubt on the Israeli claim that the West Bank is indeed God-given to the Israelis. Annexing it would imply that Israel did not have a right to it in the first place. Israelis see the entirety of the occupied territory as the “Land of Israel” which in Hebrew (Eretz Yisrael) is a different concept from the “State of Israel” (Medinat Yisrael). For Netanyahu and many Israelis, his annexation move is about extending the laws of Medinat Yisrael, the state, to territory that has always been part of Eretz Yisrael, the land. It also reflects the language and concepts in the recently passed Nation-State law which called for defining Israel as a Jewish state in the “Land of Israel.” Third, this is historically consistent with the language of “application” and “extension” used previously, including by Likud leaders like former Prime Minister Menachem Begin when he annexed the Golan Heights in 1981 with a thin Knesset majority.

What is the Jordan Valley?

The occupied West Bank and Israel are separated from the Kingdom of Jordan in the east along most of its western border by the Jordan River which flows between the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias) and the Dead Sea. Much of the territory in the West Bank and in Jordan on the opposite side is mountainous and at a much higher elevation, except for the low-lying banks of the Jordan River. This makes the valley region important for several reasons. First, from a strategic perspective, the low-lying land is easier to traverse, and the Israelis insist that it is part of a buffer they want to retain to defend against attacks from the east. Second, logistically, it is very important because of the ease of transport through it. There is a single road, Road 90, that runs from the northernmost part of the eastern half of the country all the way down to its southernmost tip. Throughout, and particularly in the West Bank, the road follows the valley to avoid the difficult mountainous terrain to the west. Between this road and the center of the West Bank, there is no main access road running north and south. The only other road, Road 60, which runs in the center of the West Bank, serves many Israeli settlements, is off-limits to Palestinians in many areas, and can often be shut off to them entirely. Third, the low-lying valley is fertile territory that is extremely valuable for agriculture. Dominated by Israel today, the Jordan Valley is an agricultural and natural resource hub, on which the future economy of a Palestinian state can rest.

The low-lying valley is fertile territory that is extremely valuable for agriculture. Dominated by Israel today, the Jordan Valley is an agricultural and natural resource hub, on which the future economy of a Palestinian state can rest.

But more than just territory, the Jordan Valley is also home to 65,000 Palestinians, including in the city of Jericho. There also are some 11,000 Israeli settlers. Today, outside of Jericho, the Palestinian community in the area is sparse, but there are also isolated Palestinian towns and villages. It was not always this way. Much of the area’s traditional population had been forced to move in the years since Israel occupied it in 1967. Some estimates put the decline in population in the Jericho subdistrict after the 1967 war at 83 percent.

It should go without saying that the Jordan Valley, comprising almost 30 percent of the West Bank, is a central component of the West Bank and is valuable for several reasons enumerated above. Additionally, however, it is a necessary component of the territorial contiguity of any Palestinian-administered territory in the West Bank, independent or under occupation. The already hard-to-imagine idea of a Palestinian state in the West Bank, given current realities, becomes even more fanciful if the Jordan Valley is not part of it.

Annexation Fallout

An essential question arises: what would happen if Israel actually went ahead with formally applying sovereignty to some or all of Area C, which is 60 percent of the West Bank and includes the Jordan Valley as well as all of Israel’s settlements in the occupied territory? There is a case to be made that this change would be seismic; but also a case to be made that it will have little impact.

On the one hand, annexing Area C would be very significant because it would formally and through the instrument of law, change the status quo of the West Bank. As with the annexation of both the Golan Heights and Jerusalem, formally annexing Area C would create a new and significant obstacle that could only be reversed through a reversal of the law. Once annexation is formally codified in Israeli law, it would be much harder to get the Israelis to reverse it, no matter how immense the pressure can be. With little to no pressure ever applied on Israel, it is hard to imagine a scenario where formal annexation would be reversible.

Much like the cases of annexing Jerusalem and the Golan, this time international condemnation would be quick to come. But the problem is and has always been that the United States will prevent the international community from actually pressing Israel to uphold its obligations under international law. With such an eventuality, the new status quo would most likely be normalized.

Once annexation is formally codified in Israeli law, it would be much harder to get the Israelis to reverse it, no matter how immense the pressure can be.

Unlike the annexation of Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, however, the takeover of Area C would come after a long period of time in which a so-called ‘peace process’ drove the goal of an independent Palestinian state into the international consensus. The annexation would have to force a reevaluation of said consensus because it makes clear that an independent Palestinian state is an impossible goal to achieve; pretending otherwise would no longer be tenable. Moreover, annexing Area C and cutting off the Jordan Valley would practically mean isolating the remainder of Palestinian territory in the West Bank as islands surrounded by Israeli-held territory. In short, it would formalize the current situation.

This is where the second case of an inconsequential annexation can be made. As of today, Israel controls Area C which is off limits to Palestinians. In many ways, Israel has all but annexed it formally. Israeli settlers in Area C participate in Israeli political life and society as do all other Israeli citizens. They vote in elections, pay taxes to the central government, and move in and around the country like all other Israelis. The government continues to fund their areas, and often disproportionately so compared to other Israeli population centers. As for the situation on the ground and the daily lives of Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank, little would likely change.

For this reason, the optics of Netanyahu’s annexation are the biggest variable. How would this move, should it happen, be perceived? What would it mean for Israel’s relations with the rest of the world? Netanyahu has argued that Israel has a historic opportunity to take this step if he is reelected because of his relationship with US President Donald Trump. Given the weight of the United States, it is not hard to see how annexation would become acceptable if Trump went along given how European leaders tend to follow the United States on this issue, even if they appear reluctant. Creating a new normal is what Netanyahu is likely banking on; resetting the international consensus to accept a formalized system of apartheid and using Trump’s blessing to do so.

Given the weight of the United States, it is not hard to see how annexation would become acceptable if Trump went along given how European leaders tend to follow the United States on this issue, even if they appear reluctant.

Real or Bluster?

There are two ways to look at Netanyahu’s election promises on annexation. This can be seen as either the pre-election bluster of a desperate politician seeking every last right-wing vote, or a real commitment that is likely to be realized. The truth is, both can be possible.

Netanyahu is no stranger to pre-election antics and has deployed them repeatedly and more intensely as he competed for right-wing votes ahead of the last several Israeli elections. In 2015, for example, he famously declared on the eve of the election that there would never be a Palestinian state if he was elected and made racist remarks to incite against Palestinian citizens of Israel voting at the polls. In last April’s election, after which he couldn’t form a coalition government, he also made an annexation promise at the last minute and the theme of the entire campaign was imbued with anti-Arab racism. Once again this time, he has been even more vocal and detailed about annexation and even more vociferous in his anti-Palestinian racism.

This track record forces the question whether Netanyahu is just a hack who is putting on the same show for votes every time. The answer is partly in the affirmative, but the way in which he has done so is telling: he uses more exaggeration every time, indicating that the Israeli polity has indeed moved decidedly to the right. Moreover, his moving more extremely to the right in his promises and antics to secure conservatives rightwing votes has forced the so-called center-left rightward as well. In fact, the main opposition party, the Blue and White Party led by former Chief of Staff Benjamin Gantz, did not object to Netanyahu’s Jordan valley annexation promise in principle. What they objected to was that he stole their idea. They too committed to holding onto the Jordan Valley and most of the settlements forever.

The main opposition party, the Blue and White Party led by former Chief of Staff Benjamin Gantz, did not object to Netanyahu’s Jordan valley annexation promise in principle. What they objected to was that he stole their idea.

Some will argue that campaign talk is just that, talk, and that it does not matter how public opinion is continuing to move rightward in Israel since it is shaped by leaders. According to a recent poll, some 48 percent of Israeli Jews today support annexing Area C while only 28 percent are opposed. But for leaders to be able to credibly shape and shift public opinion in another direction, they would need to have legitimacy and good standing in a society that is increasingly rightist. It is hard to see how an Israeli leader can emerge and argue for a completely different direction. Netanyahu has spent his entire political career shifting the Israeli public to the right and continues to do so today in more aggressive ways than ever, thanks to the success he has had over the years. His opponents have no choice but to try to compete with him in the public sphere he has created. Even if Netanyahu does not become the next prime minister of Israel, his ideas, including annexation, are likely to govern and shape Israeli politics for years to come.