The signature blueprint of any US president is the federal budget. Donald Trump is giving us an insight into how he views the world and what resources he intends to employ in advancing US interests abroad. The FY 2018 defense budget proposal alters the way the United States projects its power while offering no levelness between defense and diplomacy. However, the chances that the current version of the proposal will pass through the US Congress are slim; a prominent Republican Senator called it “dead on arrival.”

A complete draft of the defense budget will not be ready for public dissemination until May 2017. What we have so far is what the director of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Mick Mulvaney termed “a topline number only.” This policy analysis will focus on key trends in the budget proposal and what impact it might have on US foreign policy.

Salient Features of the Budget

Defense budget priorities: The focus of the FY 2018 defense budget is restoring US nuclear capabilities as well as ensuring military readiness to have enough resources to expand the number of airstrikes and special forces in the campaign against the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in Syria, Yemen, and Somalia.

Pay as you go: There is no parity between defense discretionary spending ($603 billion) and non-defense discretionary spending ($462 billion), an issue that will draw resistance from Democrats in Congress. The increase in the defense budget will be offset by equal reductions in non-defense spending.

Discrepancy in numbers: While the White House has been talking about a 9.4 percent increase in the defense budget ($54 billion), these numbers do not provide the full picture. Senator John McCain (R-Arizona) noted that the actual increase is $18.5 billion, or 3 percent more than Obama’s FY 2018 defense budget.

Depleting resources of diplomacy: The State Department and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) budgets will be cut by nearly 37 percent in the White House proposal. That will significantly slash US foreign assistance programs, which are less than 1 percent of the overall budget.

Pentagon Shifts to Warfighting Readiness

The strategic shift that Defense Secretary General James Mattis brought to the Pentagon was fleshed out in a January 31, 2017 memo. Mattis believes the Obama Administration focused on future threats more than current military readiness, hence he offered a three-phase transition plan to correct that pattern in the defense budget. Phase one requires an FY 2017 budget amendment request (already sent to OMB) to address “urgent warfighting readiness shortfalls” and meet new requirements to accelerate the campaign against ISIL.

Phase two, which is the proposed FY 2018 budget, is expected to balance between pressing programmatic shortfalls and continuing to rebuild readiness. That effort will include, according to the memo, buying more critical ammunitions and growing force structure at “the maximum responsible rate.” After focusing on the short-term investments in military readiness, the Pentagon will produce phase three in 2018 that will include the National Defense Strategy (NDS) with a budget vision for FY 2019-2023. NDS is expected to include building capacity, improving lethality against a broad spectrum of potential threats, and reforming the way the Pentagon does business.

The US government’s foreign assistance in 2017 and 2018 will have significant focus on what Trump has called in his first address to Congress the mission to “demolish and destroy” ISIL. The phased approach to the defense budget means that the Pentagon expects the war against ISIL in Iraq and Syria to be wrapped up by 2018. It also reflects plans to intensify strikes over ISIL and al-Qaeda operatives in Syria as well as to expand operations against al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in Yemen and al-Shabab in Somalia.

The new approach to the war on ISIL not only requires allocating budget resources for more drone sorties and ammunitions, but the Pentagon is also expected to recommend deploying additional troops in both Syria and Iraq as well as in Somalia, where Washington aims to start providing air and ground support for the fragile national army. More importantly, the defense budget increase will reportedly include additional resources for establishing “a more robust presence in key international waterways and choke points” such as the Strait of Hormuz and the South China Sea.

The Trump Administration’s defense budget increase is informed by the Mattis memo and by the short-term needs to expand the war on ISIL—and not by a long-term vision to rebuild the military. However, the trend of increasing the size of the military force contradicts the efforts to balance the federal budget and has no strong rationale at a time when the number of US soldiers deployed in war zones is decreasing or rather limited. While Obama’s defense budget proposal asked to cut the number of military service members by 27,015 for active and 9,800 for reserve, the FY 2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) released by Congress ended up increasing the force by 24,000 active and 12,000 reserve personnel. During his presidential campaign, Trump promised to further expand the active-duty army force from 475,000 to 540,000, a return to President George W. Bush’s wartime troop level.

Defense Budget: Trump Versus Obama

In its nascent defense budget proposal, the Trump Administration’s military spending does not necessarily exceed by far what the previous administration allocated. In fact, the current White House is benefiting from the increase in the defense budget approved by the Obama Administration in the past few years, in particular in FY 2012. The FY 2017 defense budget had a total of $611.2 billion, which included $523.7 billion in discretionary spending and $67.8 billion for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO). However, the actual defense budget was $627.1 billion if one counts the $7.8 billion for discretionary programs outside the jurisdiction of Congress and the $8.1 billion for programs funded by mandatory spending.

Here is why the White House’s numbers require further explanation. The 2011 Budget Control Act set a spending cap of $549 billion for 2018, and Trump’s White House is now proposing $603 billion, hence the stated $54 billion increase. However, the Obama Administration had already approved going beyond the $549 billion cap and had proposed for FY 2018 a defense budget of $585 billion, which makes the actual increase of Trump’s proposed budget only $18.5 billion. The previous administration did not shy away from increasing the defense budget. Indeed, it is worth noting that the $682 billion defense budget of 2012 was more than the combined military spending ($652 billion) of China, Russia, the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Saudi Arabia, India, Germany, Italy, and Brazil.

Impact on US Diplomacy and the Middle East

The State Department is accustomed to fighting for budget appropriations with members of the House and Senate as the congressional inclination to slash the international affairs budget has been a recurrent theme. In October 2011, the State Department and foreign operations budget was cut by 8 percent by the full Senate Appropriations Committee and 18 percent by the House Appropriations Committee. However, and in an unprecedented way, these current significant reductions came from the White House this year and by rates never seen before. Incidentally, the only hope now to save the State Department’s budget is through dissenting voices on Capitol Hill. Indeed, the resistance to the 37 percent cut is growing among both Democratic and Republican members. Furthermore, over 120 retired US generals signed a letter on February 28, 2017 warning against cutting the State Department budget. The letter quoted Mattis saying in 2013, “if you don’t fully fund the State Department, then I need to buy more ammunition.”

To put things into perspective, it is important to note that the federal government spends nearly $52.8 billion on the State Department’s overall operations and programs. Since FY 2012, the Obama Administration began to divide the international affairs budget request between “core” budget and Overseas Contingency Operations, in a similar way to the defense budget. Typically, 70 percent of the amount is the base budget and 30 percent goes for OCO. If the 37 percent budget cut holds, the State Department will be left with around $31.5 billion, which means an $18.5 billion cut. Foreign aid in FY 2017 amounted to $22.7 billion, hence these reductions will have significant impact on the effectiveness of US diplomacy.

While adding $18.5 billion to the massive defense budget will not make a big difference for the Pentagon, a reduction by this amount would basically paralyze the State Department’s operations. Budget reductions will likely compel both State and USAID to lay off staff both in Washington and abroad, including security contractors at diplomatic facilities overseas. The Trump Administration is also considering the cancellation of at least some of the over 50 positions of State Department special envoys and representatives, which cover issues regarding Syria, Libya, Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, and the implementation of the Iran nuclear deal.

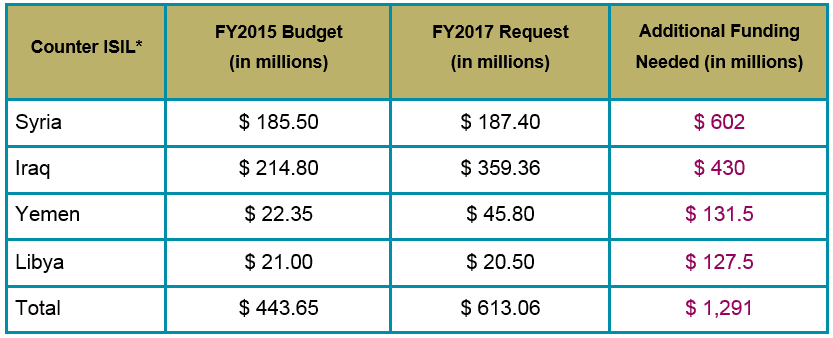

In terms of the Middle East, until we have a better picture of budget justifications, it is hard to measure quantitatively the impact if the White House’s defense budget goes through. In FY 2016, the requested overall regional aid programs amounted to $140 million on average, while non-humanitarian aid to countries reached $7.14 billion, nearly 13 percent of the international affairs budget. The total amount of non-humanitarian assistance for 14 Arab countries in FY 2015 amounted to $3.39 billion, nearly equal to the aid given to Israel ($3.1 billion). No impact should be expected on the current State Department budget levels to counter ISIL, while keeping in mind the gap between prior budget requests and actual funding needs.

*State Department budget for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO)

Next Steps: Bureaucratic Rope Pulling

In a process called “passback,” on February 27, 2017 the White House sent out the proposed allocations to the federal agencies for review and these budget proposals were due back to OMB on March 3, 2017. The numbers will then go to Congress by March 16, while the full budget and its policy justifications will not be rolled out until May. Meanwhile, the US government continues to be funded by a short-term Continuing Resolution (CR) through April 18, 2017.

The Trump White House floated the 37 percent cut as a starting point for negotiations with both the State Department and Congress. We have yet to see how much can be saved from the $52.8 billion budget after deliberations on Capitol Hill. The next battle will be in the congressional committees on issues of budget appropriations, policy priorities, and spending caps. Based on the austerity measures included in the 2011 Budget Control Act, even automatic cuts between defense and non-defense discretionary spending will be triggered in the federal budget if these expenses exceed a certain cap. Trump and the hawks in Congress will undoubtedly circumvent sequestration by allocating defense spending under emergency funding and/or under the OCO budget, a trend that has been occurring in the past few years. Both chairmen of the Senate and House Armed Service Committees, Senator John McCain (R-Arizona) and Congressman Mac Thornberry (R-Texas), are demanding a $640 billion defense budget for FY 2018, which represents a 9 percent increase from Obama’s FY 2018 defense budget. In return, for years Democrats in Congress have rejected attempts to exceed defense spending caps unless they were matched by a comparable increase in non-defense spending.

The Trump Administration will face several budget scenarios in the spring of 2017: 1) tensions over the budget deficit and health care legislation could derail the negotiations between the White House and Congress, hence a government shutdown could occur once again; 2) the White House could alternatively use the OCO budget to increase the defense budget, an option that was once highly criticized by Mulvaney himself (who described the measure as a “slush fund”); 3) for the sequestration to kick in, the OMB will need to issue a guidance, but there is no indication the White House is even willing to consider that; and 4) the White House might govern on continuing resolutions, as Obama did, since reaching a budget deal seems to be elusive.

Final Thoughts on Trump’s Budget

The concern is how far the Trump Administration is willing to go to militarize the federal budget. One cannot ignore the underlying message and context behind these symbolic budget numbers, in particular for countries on the forefront of the war against terrorism. Iraq, Syria, Libya, and Yemen can be lethally and unilaterally bombed on a daily basis; however, their citizens (except for Iraq according the president’s new executive order) are banned from traveling to the United States. Mosul and Raqqa can be destroyed in the process of liberating them from ISIL; however, US funding might not be available for their reconstruction or for the displaced persons who hope to return home. The White House’s message, through the budget proposal, basically means that the United States is willing to deploy drones and navy ships instead of sending diplomats and aid across the world. Middle Eastern governments will, of course, welcome the fact that the new administration is willing to provide military assistance with no strings attached or preconditions for the development of political reforms and implementation of human rights. Indeed, the Trump Administration’s defense budget proposal has the potential to take us back to the era before the “Arab Spring,” when US foreign policy was complacent regarding Arab authoritarianism.

At this juncture in Middle East politics, slashing foreign aid will also cement the narrative about the waning of US influence in the region. The international affairs budget cuts come as the US presence was barely felt in the recent Syrian peace talks in Astana and Geneva. Further, Russia’s show of force has been expanding, and the bedrock of US policy in the Middle East—the two-state solution between Palestinians and Israelis—is becoming an afterthought in Washington. Sustaining US influence abroad clearly has a price tag. That’s the core of the budget battle in the coming weeks.