Why would the wild winds blowing out of Washington keep Gulf rulers up at night?

On the surface, it may seem that they have little cause for worry, since the Trump administration has not specifically directed its aggressive trade and foreign policies at the Gulf states. Ruling elites in the Gulf also have a higher comfort level in President Donald Trump and his circles than do other US partners, owing to their shared interests in real estate development and bilateral investment ties.

But the collective weight of Washington’s nationalistic turn and embrace of tariffs, its poor treatment of allies, and its disdain for the rules-based international order represent cause for worry in one of the world’s most globalized regions. The open economies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) are at a major disadvantage due to their high dependence on free trade, unfettered markets, and nonalignment.

Gulf sovereign wealth funds are grappling with zig-zagging share valuations, while the falling oil price—compounded by a falling dollar—is throttling capital flows supporting Gulf economic diversification schemes. Additional risk exposures include misaligned climate strategies and the potential for military blowback from Iran or Yemen in response to US-Israeli attacks against the Houthis. In aggregate, these factors weigh heavily on the attractiveness of the Gulf for foreign investment.

While some international investors are pulling capital out of American assets, Gulf investors are piling in.

Of course, for the Gulf, there are factors mitigating these shocks. Gulf leaders appreciate the Trump administration’s embrace of fossil fuels and de-emphasis of climate action. The US turn to “energy pragmatism” offers breathing room for Gulf diversification investments to do the long-term work of complementing and eventually replacing oil and gas revenues.

And while some international investors are pulling capital out of American assets, Gulf investors are piling in—at least into the US hydrocarbon sector, whose attractions include its convenient hedging of geopolitical risk, including from the Trump administration’s trade wars. A proliferation of joint ventures (JVs) between US oil majors and Gulf national oil companies (NOCs) could provide useful insulation from US policy volatility.

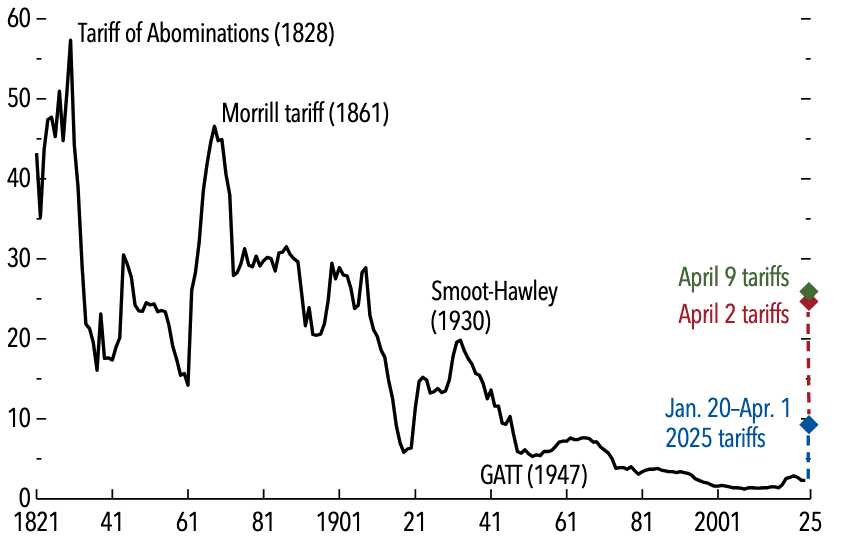

Figure 1: US Effective Tariff Rates on All Imports (Percent)

US tariffs enacted or announced by the Trump administration in historic context. IMF estimates an effective rate of 25 percent. Sources: IMF World Economic Outlook April 2025, executive summary; US Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, 1789–1945; US International Trade Commission; and IMF staff calculations.

Tariffs Weigh on Oil Incomes and Diversification Drives

Trade restrictions are anathema to the Gulf’s open economies, which are built around free trade, capital mobility, and two-way investment. On again, off again US tariffs are already curtailing global economic growth, which is strongly correlated with oil demand. The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Forecast for 2025 cited the US-led trade war as the reason for a downward revision in global growth, from 3.3 percent to 2.8 percent, well below the average of 3.7 percent over the first two decades of the 2000s. The IMF also downgraded forecast gross domestic product growth in Saudi Arabia, and a Reuters poll found reduced growth expectations for the United Arab Emirates (UAE) as well as other regional oil exporters.

Gulf countries with budget breakevens above $60 per barrel face deficits that they will have to finance.

Trump’s trade war is just one factor depressing oil and gas demand, prices, and rents. Faster-than-expected decline in Chinese gasoline demand is also taking place amid a rapid uptake in electric vehicles and liquefied natural gas-powered trucking. On the supply side, the recent OPEC+ decision to relax production quotas is putting more downward pressure on prices. Meanwhile other US actions such as imposing sanctions on oil shipments from Iran and Venezuela could offset some of the oil price decline.

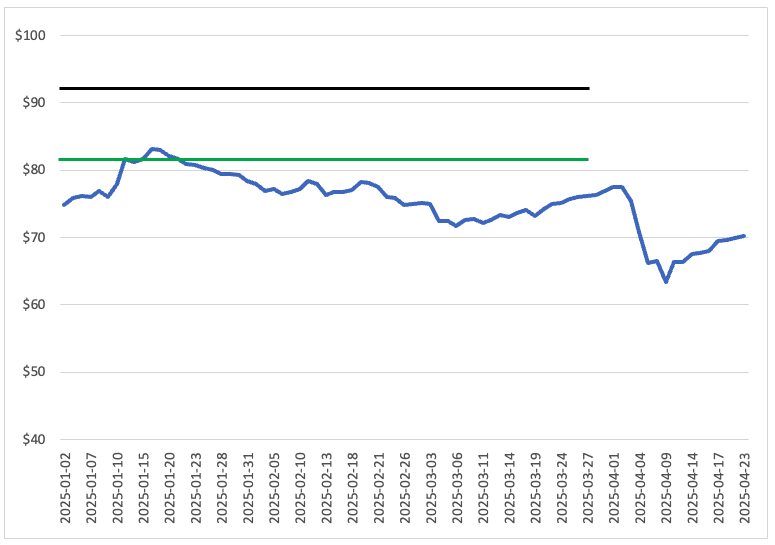

In the Gulf, producer countries with budget breakevens—the price per barrel necessary for balancing the national budget—above $60 per barrel face deficits that they will have to finance, probably by debt. Figure 2 shows that Saudi Arabia, which needs a price of $91 per barrel to balance its 2025 budget, and Kuwait, which needs oil at $81 per barrel, are already out of money.

Figure 2: OPEC Crude Basket Price and GCC Budget Breakevens in 2025

OPEC crude prices remained below breakeven budget prices in Saudi Arabia ($91) (black line) and Kuwait ($81) (green). Other breakevens were Oman $57; UAE $50; and Qatar $45. Source: OPEC (oil price), IMF via St. Louis Fed (budget breakevens).

Falling oil prices come as Gulf countries find themselves in “cash crunch” mode, as they raise capital for nonoil economic diversification ventures known in Saudi Arabia as “giga projects.” These are aimed at insulating economies and state budgets from eventual climate policy-driven reductions to petroleum rents. Weak oil prices make Gulf projects more dependent on foreign direct investment (FDI), but FDI was not sufficient even when oil was above $70. Inward FDI to Saudi Arabia in 2023 was $26 billion, well shy of its 2030 goal of $100 billion/year.

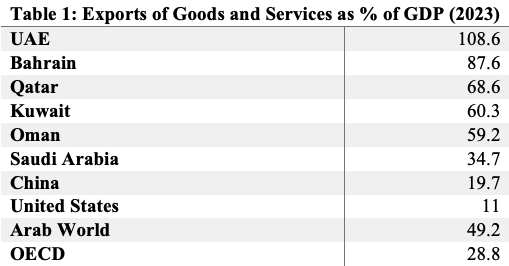

Deep dependence on trade means the Gulf countries are more exposed to barriers, although they do not export much oil and gas to the United States. For instance, exports of goods and services from the UAE represented 109 percent of its 2023 GDP, higher than all except a few trade stalwarts such as Luxembourg, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Ireland. Saudi Arabia’s was the GCC’s lowest at 35 percent, but even that was nearly double China’s 20 percent and more than triple the United States’s 11 percent, World Bank data show (Table 1).

Source: World Bank 2025

Climate Divergence

On the positive side, Trump’s return to the scene has relieved stress in the Gulf about a climate-driven clampdown on oil and gas combustion. The administration has joined Saudi Arabia in embracing the “pragmatic” acceptance that large volumes of fossil fuels will remain in the world’s fuel mix for decades. Gulf policymaking elites visibly enjoyed the more favorable messaging during the March CERAWeek energy conference in Houston, after years of tough rhetoric.

But not all of the Gulf’s climate concerns correlate with Trump administration priorities. These include defunding of climate research and Washington’s reprised embrace of coal, although here the rhetoric outpaces investor interest. The Arabian Peninsula’s climate concerns do not end with the potential threat to oil rents. They include physical climate damage to their homelands, with summer high temperatures expected to rise by 0.1°C to 0.7°C per decade. One recent analysis predicts that the Middle East will face higher damage costs than any other region in the world, taking almost double the US GDP hit by 2050. Experts anticipate that the Middle East will experience a loss of 19 percent of GDP due to climate change, the most of any region in the world.

Extreme temperatures along with alternating drought and flash flooding have already rendered global warming palpable in the Gulf, and unabated emissions only raise the costs of adaptation. In this light, Trump’s broad reversals demonstrate little understanding of the Gulf’s “lose-lose” climate predicament and the need for targeted action.

Another hint of the differing priorities can be seen in the increased willingness of Gulf NOCs to invest in alternate forms of energy. Low-carbon spend among global oil firms—formerly led by a now retrenching BP—is headed by TotalEnergies, closely followed by two national oil companies in the Middle East, Saudi Aramco, which is earmarking near $5 billion per year, and Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC), which is pledging more than $4 billion, according to Wood Mackenzie. Exxon is another surprise big spender on low carbon.

FDI Needs Stability and Peace

The Gulf’s response is that economic transformations are needed to diversify deep oil dependence. Foreign investor partners will be needed to assist. However, FDI requires more regional stability, not less. As a result, Gulf governments have sought to “de-risk” fraught relations with neighbors, particularly Iran, where the lesson of the 2019 attack on Saudi Aramco’s Abqaiq oil processing plant remains a potent reminder of the sorts of vulnerabilities that give foreign investors pause.

Unfortunately, Trump administration perturbations appear to be increasing geopolitical risk exposures, undermining attractiveness for inward FDI that is needed for Saudi giga projects and other efforts. Israel’s destruction of Gaza has shocked the Arab world, as has backing for the assault from both the Trump and Biden administrations. Recent Israeli incursions into and operations in Lebanon and Syria—where much of the military infrastructure has been destroyed with American acquiescence—add to uncertainty about US adherence to a rules-based international order. Gulf leaders have also distanced themselves from US bombing in Yemen, in hopes of averting a revived Houthi drone and missile assault on their territories.

Foreign investors eyeing Gulf opportunities have numerous geopolitical risks to consider.

Furthermore, Trump administration designs on Greenland, Canada, the Panama Canal, and Gaza suggest the potential for a new period of territorial acquisition like that of the mid- to late-1800s when an expansionist Washington added territory through purchases or seizures. Weakening recognition of national sovereignty is bad news for small or weak states anywhere, but particularly in the Middle East, where borders have largely been enforced by adherence to international law and the UN Charter. Regional hegemons could leverage the loosened rules to make territorial expansions of their own. Syria and Lebanon are in the weakest positions.

All this means that foreign investors eyeing Gulf opportunities amid the historic Vision 2030 opening in Saudi Arabia have numerous geopolitical risks to consider. These include risks emanating from ongoing conflicts as well as the palpable threats from a possible future US-Israeli attack on Iran. As Abqaiq demonstrated, when Iran responds to hostilities from the United States and Israel, its retaliation options include targeting America’s Gulf allies. In this climate, Saudi diplomacy to establish itself as an “investment-friendly environment” is an uphill battle.

Hedging Through US-Bound FDI

How might Gulf states reduce or hedge risk of counterproductive intervention by Washington? The emerging response: bolster influence in Washington via splashy announcements of JVs and foreign investment. These include Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s pledge to invest $600 billion in the United States—which Trump suggested ought to be rounded up to $1 trillion.

Unrealistic pledges aside, there are myriad examples of Gulf national oil companies internationalizing their business models by broadening portfolios to include US partnerships and investment. ADNOC, along with Saudi Aramco and QatarEnergy (QE), are the most active.

December’s launch of XRG, ADNOC’s international lower-carbon investment arm, is a dramatic example. XRG is rapidly assembling acquisitions in three focus areas: international gas and LNG; chemicals and plastics; and low carbon hydrogen and ammonia. The ADNOC subsidiary targets $80 billion in investment in the broad space that lies between oil and renewable power. XRG’s acquisitions or interests include US targets: a 35 percent stake in Exxon’s proposed Baytown low-carbon hydrogen project, and a stake in NextDecade LNG in Texas (with further buy-in from the UAE’s Mubadala).

QE’s spate of foreign investment includes JVs with Exxon and Chevron in seven exploration blocks off Egypt and two more off Cyprus. QE ventures in the US include the Gulf Coast petrochemicals JV called Golden Triangle Polymers with Chevron Phillips, and the Golden Pass LNG terminal operated by Exxon. As this author argued in a 2022 analysis, strategic choices in joint ventures can incubate more interest by Washington in a small country’s well-being.

Where once Saudi Arabia held a huge trade surplus, the balance has shifted in favor of the US.

By the look of the US-Saudi trade balance, Saudi Arabia can probably relax about being targeted by Trump’s “reciprocal” tariffs. Where once Saudi Arabia held a huge trade surplus, the balance has shifted in favor of the United States as imports of Saudi crude have plummeted since 2013. According to the Saudi General Authority for Statistics, the kingdom showed a trade deficit with the United States between 2020 and 2024, except for 2022.

Saudi Aramco also has a long investment history in the United States. It wholly owns and operates the Motiva oil refinery in Texas, the largest in the United States. Aramco is also looking to take a 25 percent stake in Sempra’s LNG export terminal in Texas while Saudi petrochemicals firm SABIC operates a 50-50 joint venture ethane cracker in Texas with ExxonMobil.

Amid these ventures the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) has quietly cut its US holdings over the past three years, from $42 billion to $20 billion in March 2025 The PIF’s investment mission has shifted toward domestic diversification priorities, covering for those elusive foreign investors.

Can Gulf investments help to modulate the Trump administration’s approach to the Middle East? Maybe. At a minimum, they buy Gulf leaders a seat at the table.

Is Autonomy a Better Route to Stability?

Frustration over the Gulf governments’ perceived inability to steer the region’s destiny certainly predates the Trump administration. Such frustration has long been a staple of Iran’s diplomatic outreach. Regional pro-sovereignty themes are now being expressed in the Arab monarchies as well.

The Saudi think-tank the Gulf Research Center (GRC) has articulated new Saudi foreign policy tenets based on multi-alignment, diversification, mediation, and sovereign autonomy. These views resemble Iran’s long-running call for “collective security,” in which interloping superpowers are supposed to remove themselves from the region. The Saudis have not adopted such language, but the Gulf’s discomfort at being caught up in the Washington-China competition is implied throughout.

But in other areas, the GRC authors express critical views of Washington’s approach to the region. GRC studies emphasize conflict prevention, crisis management, and regional cooperation. Much of this is based around “assuring foreign investors of the country’s security and stability” so they will bring capital to bear on the 14 Saudi Vision 2030 giga projects.

Alliances once restricted to Western powers are broadening into multi-aligned partnerships with China, other BRICS states, and others. Nowadays, the Gulf exporters rely on China’s market for its oil exports and import of Chinese solar panels and batteries, while still hoping that American firepower will provide hard security. It is a delicate balance.

Perhaps it is no wonder that conflict mediation, a specialty of Qatar and Oman, is being adopted by other Gulf states as well.

The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

Featured image credit: Kuwait News Agency/Amiri Diwan