In its first few months, the Trump Administration has laid out an ambitious agenda as it seeks to manage difficult foreign policy conundrums inherited from the Obama Administration, thus setting a new course in the US approach to the world. Along the way, it also faces major challenges in the Middle East such as defeating the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) threat, confronting Iranian regional ambitions, and managing a serious and growing crisis within the GCC which pits Saudi Arabia and its allies against Qatar. In addition, the Iraqi Kurdish referendum on independence, scheduled to take place in September, looms on the horizon and with it the possibility of the breakup of Iraq down the road.

Ideally, a new administration would have a strong foreign policy leadership team in place while assiduously moving to staff lower levels of the State Department, particularly at the assistant secretary level. State would then be asserting its preeminent role within the interagency and articulating a coherent strategic vision of America’s place in the world as the White House finds its footing.

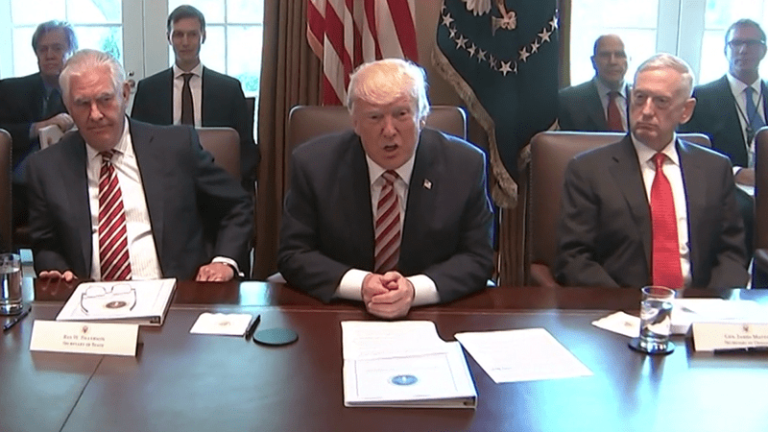

Today’s reality, however, is much different. The Trump Administration has failed to speak with one voice, moved slowly to staff key positions, and laid out an international affairs budget designed, for all intents and purposes, to permanently downsize the foreign affairs agencies and narrow the scope of their missions. The Department of State’s influence with the White House is minimal, as is its authority within the broader US foreign policy structure. The Trump Administration’s approach to the department and other US foreign affairs institutions is one of the most visible manifestations of presidential advisor Stephen K. Bannon’s vow to push forward with the “deconstruction of the administrative state.” It is a process from which the Department of State will be slow to recover—certainly under this presidency, and possibly for quite some time to come. To be sure, the institutional integrity and authority of American foreign policy has rarely been less certain.

The Troubles at State

The process of staffing the executive branch in general—an estimated 560 key executive positions—remains extremely slow; only 42 nominees have been confirmed so far. Among federal agencies, the State Department has fared particularly badly; out of 120 State Department leadership and ambassadorial positions, only nine have been confirmed, including the Secretary, the Deputy Secretary, and the Permanent Representative to the United Nations. There are no nominees for most positions, including the assistant secretaries for the department’s six regional bureaus. Only one ambassador to a Near East country, David Friedman for Israel, has been confirmed. As a result, policy development and implementation within State have slowed to a crawl.

The staffing issues at the top have trickled down to the rank and file. Large numbers of career diplomats remain unassigned, their careers on hold pending decisions on assignments for the senior ranks. Shortly after the inauguration, a number of senior career diplomats were forced out on very short notice. There is a general worry that the situation is not merely a result of a new administration settling in, but of a concerted attempt to permanently reduce the career ranks and hobble the institution. As one senior foreign service officer told this writer, the administration seems “determined to deconstruct the Department by radically underfunding it, forcing senior FSOs [Foreign Service Officers] out, leaving many top positions unfilled, and marginalizing State in every possible area of foreign policy. For the career service, this may be our biggest crisis ever.”

The administration’s budget proposal for international affairs spending and for the State Department, submitted in May, tends to bear this out. Steep cuts would begin in FY 2018, with State Department and foreign aid spending dropping from $39.7 billion to $28.2 billion, representing a one-year reduction of 21.9 percent. But the most damaging cuts would accumulate over a longer period. The budget proposal anticipates total international and humanitarian assistance over a ten-year period of $347.9 billion, a ten-year reduction of 47.8 percent over baseline projections under current law. Funding for the “conduct of foreign affairs,” which includes State Department operations, embassy security, construction and maintenance, and several other categories would similarly face a 51.1 percent cut over ten years from baseline spending of $89.9 billion. The budgets of the Woodrow Wilson Center and the US Institute of Peace, two important players in the foreign policy ideas factory, would also be zeroed out.

All this comes in the context of major personnel cuts and a restructuring that may axe numerous positions and offices. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson reportedly supports a plan to slash 2,300 foreign service and civil service positions over the next two years. Numerous special envoys and functional offices seem to face possible termination. Tillerson’s staff is undertaking a “listening exercise” to gather input from all State Department employees in an online survey and in-person interviews with a smaller number to get their take on resources and mission, but no end-state concept or strategy to manage the restructuring is in evidence yet. More influential inputs may come from outside sources, including the White House and the conservative Heritage Foundation, which has written a comprehensive report on restructuring State and its functions. This report implicitly endorses personnel cuts and the downsizing of resources, while calling for the elimination of positions and consolidation of many functions now reserved to State’s regional and functional bureaus.

Indeed, the budget decisions for 2018 underscored just how the military, which would receive a $54 billion funding increase in the budget outline submitted by the White House in March, is being prioritized over diplomacy and foreign policy. Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney, when asked in an interview about defense and foreign affairs spending priorities, affirmed that “this is a hard-power budget, not a soft-power budget. That is what the president wanted and that’s what we gave him.”

Concerns about the effect of radical restructuring on State’s ability to perform its core mission have been compounded by its evident willingness to cede authority to the National Security Council (NSC) and the military, a troubling sign for the future of American diplomacy. The State Department has been cut out of many key meetings and decisions and much of the decision-making in the foreign policy sphere has gravitated to key presidential staff, such as National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster, presidential advisor and son-in-law Jared Kushner, and Bannon. The White House continues to play a major role in State Department staffing. (Tillerson’s first choice for Deputy Secretary, Elliott Abrams, a highly qualified former diplomat and currently Senior Fellow for Middle Eastern Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, was rejected by the White House, apparently for publicly criticizing Trump when he was a candidate.) Trump also tends to put more stock in advice from the military as opposed to civilians, which has reinforced the president’s inclination to look to military rather than diplomatic solutions. This has had the effect of further marginalizing the State Department.

US Leadership on the Wane

While the institutional foundations of US foreign policy are being challenged from within the government, the administration’s willingness to relinquish international leadership has begun to undermine them from without. The early decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was widely viewed as an opportunity for China to increase its economic and political influence in the Asia-Pacific arena. Trump’s notification to Congress that the administration will renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and possibly pull out if negotiations prove unsatisfactory, have prompted alarm and pushback from Canada and Mexico.

The president’s decision to remove the United States from the Paris climate accord was the latest action by the administration to prompt widespread criticism of the United States at home and abroad, and was understood by many as another abrogation of both moral and political authority.

In the wake of Trump’s announcement on Paris, doubts also have been raised about the strength of US alliances, prompting allies to reassess their relations with Washington and muse about seeking closer ties elsewhere. The president’s denigration of NATO, which he once described as “obsolete” before reversing himself, has called into question US commitments once thought unshakable. Indeed, during a testy visit to Brussels in May, Trump criticized 23 of 28 NATO members for not meeting defense spending targets; he also pointedly failed to endorse Article 5 of the NATO charter, which commits all members to mutual defense. German Chancellor Angela Merkel remarked a few days later that, “The times in which we could completely depend on others are, to a certain extent, over … We Europeans truly have to take our fate into our own hands.”

Even Canada, America’s largest trading partner and close ally, has seen the need to act more independently of Washington. In a speech on June 6, Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland said that “the fact that our friend and ally [the United States] has come to question the very worth of its mantle of global leadership, puts into sharper focus the need for the rest of us to set our own clear and sovereign course.”

To a limited but telling extent, US states and cities have begun to follow suit, charting their own “foreign policy” course on specific issues. The “sanctuary” movement, where cities across the country have promised not to cooperate with federal efforts to enforce national immigration laws, is one example. Another is the movement among a number of US states, cities, and even corporations to commit themselves to the climate goals of the Paris accord, the administration’s position notwithstanding. Similar movements reacting to other foreign policy-related disagreements with Washington might well follow.

Most disturbing is the administration’s decision to abandon moral authority on certain key issues on which the United States had long been seen as a global leader. Dropping out of the climate change accord is one example, and President Trump’s apparent affinity with authoritarian leaders, and their leadership style, is another.

This goes hand in hand with the administration’s inclination to downplay human rights in favor of diplomatic and economic deal making. Secretary Tillerson made this clear in a May 3 speech to State Department employees, in which he acknowledged that the United States would “advocate” for “freedom and human dignity” (pointedly avoiding the phrase “human rights”), but insisted that “if you condition our national security efforts on someone adopting our values, we probably can’t achieve our national security goals or our national security interests … it really creates obstacles to our ability to advance our national security interests, our economic interests.”

The message was clear—the United States would not prioritize human rights in its dealings with authoritarian states but will pursue instead a narrow transactional agenda. Trump himself has made this point with his praise of repressive leaderships in Russia, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Turkey, Egypt, and elsewhere. This development has raised serious concerns among many international human rights activists, and countries that support them, about the real agenda behind Trump’s “America First” approach.

Real World Effects

Policies can be amended and staffing issues worked out as a new foreign policy team settles in. But the Trump Administration appears to have chosen a different course, one that aims to fundamentally alter America’s concept of its role in the world, the proper exercise of power, the utility of basic institutions, and the inclination toward values-based policies with strong bipartisan support. These choices have set the United States on a course to progressively hollow out the foreign policy establishment’s institutional capacity, leading to the incipient loosening of ties with allies and the weakening of US moral and political leadership on important issues.

Once given away, US authority—and the capacity to use it—will be difficult to restore, even as new overseas challenges arise for the United States where such authority would be useful. The erosion of US leadership, whether swift or slow, will narrow US options in implementing critical foreign policy initiatives and the ability to manage the inevitable crises which require, among other things, experienced diplomats to manage them and persuasive powers to enlist the support of allies.

The foreign policy elements of the “administrative state” certainly have their flaws. But cutting them to the bone while realistically expecting to “do more with less” is a recipe for failure. In the Middle East, in particular, a range of Trump priorities may be affected, such as building new Gulf security structures, defeating ISIL, containing Iran, and tackling Arab-Israeli peace. It may thus be time to raise the alarm about the receding of American global leadership lest the United States sacrifice its interests at the altar of “America First.”