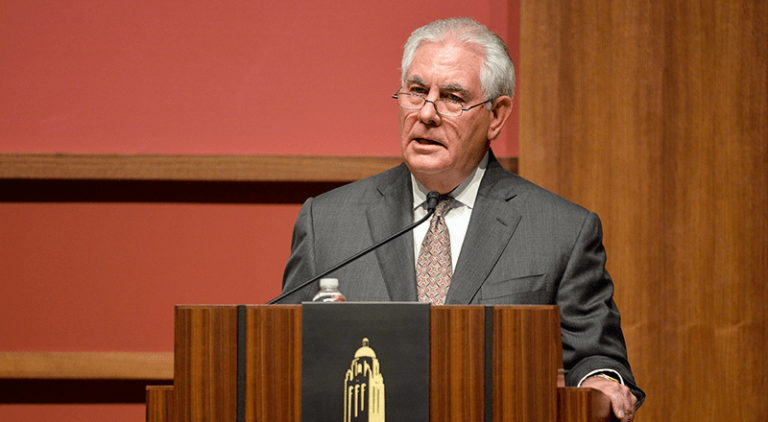

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s speech at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution on January 17, 2018 outlined what he deemed to be US policy toward the Syrian war, which will complete its seventh year in March. His comprehensive speech waded into the different sinews and complications of the Syria crisis and can be seen as the clearest indication that political Washington is not contemplating a military withdrawal from the country. Defense Secretary James Mattis had indicated earlier that the United States cannot repeat prior mistakes it made in Iraq; the early withdrawal of US troops allowed extremist and fundamentalist groups to exploit conditions in the country, which led to the establishment of a “caliphate” there by the so-called Islamic State (IS).

In his speech, Secretary Tillerson affirmed an American commitment to keeping American forces in Syria’s northeast, where they have helped the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in defeating IS and retaking its capital, Raqqa. The city is now under the complete control of a local civilian council led by the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), which are today bearing the brunt of a Turkish military assault to expel them from the cities of Afrin and Manbij.

Tillerson’s Principles

Tillerson’s speech identified five principles that summarize the goals of the new American policy in Syria: 1) a reaffirmation of US commitment to the long-term struggle against IS and al-Qaeda to eradicate their threat to the United States and its people and to American allies; 2) a commitment to a peaceful resolution of the conflict between President Bashar al-Assad and the Syrian people under the leadership of the United Nations, as was stipulated in UN Security Council Resolution 2254 that called for a unified and stable Syria without Assad; 3) an insistence on ending Iranian influence in Syria and preventing the establishment of its condominium through Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, and assuring the security of Syria’s neighbors; 4) the creation of the necessary conditions for the voluntary return of Syrian refugees and displaced persons; and, 5) continued efforts to ensure that Syria is free of weapons of mass destruction.

These principles are almost identical to what the Syrian opposition has repeatedly called for; questions remain, however, regarding how the United States intends to achieve them. For one thing, such goals require close coordination and cooperation with the Department of Defense (DoD), a condition Secretary Tillerson avoided discussing. As he supported the decision to keep American troops in Syria, he refrained from explaining what DoD’s role would be regarding such essential issues as Assad’s future, guaranteeing the return of the refugees and displaced to their destroyed cities and towns, and confronting Iranian forces or Iran-supported militias like Hezbollah and Iraqi fighters in such areas as the countryside of Aleppo and Hama. Importantly, will American troops face up to the Syrian Army if it and allied militias decide to continue their attacks on opposition areas?

Indeed, the secretary was not clear on the practical steps for keeping American troops in Syria or what their function would be. At this point, all that can be assumed is that the so-called comprehensive plan remains merely a general framework that does not have concrete steps on the ground—and this is while the Iranian and Russian military presence and role expand. It thus behooves Secretary Mattis to make his own speech to enunciate what his department might do to guarantee Tillerson’s principles, now that the US secretary of state has declared them as a new American policy toward Syria’s war.

Obama Policy Redux?

Given the chaos engulfing the Trump Administration’s policies, Tillerson’s speech represented a hesitant and restrained attempt to reverse the widespread feeling about American inaction in Syria. All President Trump has done is to order a limited response against the Shayrat military base after a chemical attack on civilians in Khan Sheikhoun last year. While that was the only action in Syria during the Trump presidency, it still exceeded what former President Barack Obama ever did militarily against the Assad regime.

Nevertheless, the Tillerson announcement comes while the Russian military and diplomatic campaign has succeeded in dominating developments in Syria through the Astana talks, where the United States had no influence. Russia has also built a political and military alliance with Turkey that has allowed Ankara to exert its influence on the Syrian opposition. Today, Russia is preparing for talks in Sochi that would work on the intra-Syrian dialogue about a new constitution; and that is after it worked to abort any UN-sponsored negotiations based on UN Security Council Resolution 2254 and the Geneva talks about political transition.

While Tillerson gave his endorsement to the concept of de-escalation zones to protect civilians, his speech avoided discussing Astana or Sochi, intimating an American reluctance to endorse Russia’s unilateral approach toward Syria. Over the last year, these venues for talks have allowed Russia to be the preeminent actor in Syria and supplanted Geneva and the UN role that produced Resolution 2254. Additionally, Tillerson’s neglect to mention any practical steps to realize his declared principles makes American policy once more ineffectual and meaningless. In a sense, the principles are a return to President Obama’s declared policy in August 2011: that Assad has lost his legitimacy. Today, American policy-makers repeatedly go back to the same general principles that, in reality, have allowed the death of over half a million Syrians and the displacement and exile of 15 million more.

The United States and Syria’s Reconstruction

While the United States grapples once again with formulating a policy on Syria’s war, Syria’s economic troubles have become more acute and daunting. The Syrian government’s latest budget has shown a precipitous decline in the country’s gross domestic product, which shrank from $60 billion in 2010 to $34 billion in 2014.

A United Nations-backed report in June 2017 estimated that 80 percent of Syrians are classified as poor, with 6.7 million lacking food security and needing immediate humanitarian assistance. Prices have risen by 1,100 percent while minimum wages have been frozen at $75 a month. A study by the World Bank has put the cost of the war has at $226 billion. [Additionally, the cost of reconstruction could eventually amount to over $300 billion.] Six out of every ten Syrians are destitute. Exports have declined by 92 percent as the trade deficit rose to 28 percent of GDP in 2017. Hard currency reserves have collapsed from $21 billion in 2010, to $1 billion in 2015. Public debt has also risen from 30 percent of GDP in 2010 to 150 percent in 2015.

In the first four years of the war, 538,000 Syrians lost their employment, raising the number of the unemployed to 6.1 million. Unemployment is about 78 percent among the youth. These figures mean that Syria may need up to 30 years to recover to pre-2011 levels—that is, if the war ends, reconstruction begins, and full security is maintained. Many believe that this is impossible given current developments and trends in the country.

The United States and Regional Conflicts

Tillerson repeatedly reminded his audience of the necessity to stand up to Iran in Syria and prevent it from realizing its dream of a Shia crescent from Iran to Lebanon. He also spoke of the danger that Iran represents to Syria’s unity, Syria’s ability to reach and undergo a transitional process, and the country’s normalization with regional states. What was missing, however, was an American roadmap to help the Free Syrian Army in fighting Iran-supported militias. Leaders of this US-supported army have recently exposed how the United States has reneged on promises to help their units on the Syrian-Iraqi border; they had been engaged in fighting Hezbollah and Iraqi Shia militias, but Washington ordered these units to withdraw from the battles there.

What was surprising in the secretary’s speech, however, was his declared support of Turkey’s military operations in northern Syria that are targeting Kurdish forces in Afrin and Manbij. While expressing his gratitude to the SDF for helping to defeat the Islamic State, he still called on them to reflect the ethnic composition of the area if they want to have a role in the transitional process. This was in reference to the almost fully Kurdish component of the SDF that occupied largely Arab areas like Raqqa and Deir Ezzor.

The Kurdish predominance in those areas has given Turkey the necessary justification to launch military operations against the YPG, which it perceives as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), considered a terrorist organization by both Ankara and Washington. This difference of opinion about the YPG has precipitated tensions in US-Turkey relations that have included accusations by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan that the United States is supporting terrorist organizations. Erdoğan has also vowed to abort American plans in Syria, especially the building of a border force of 30,000 fighters mainly from the Kurdish-dominated SDF, thus prompting Tillerson’s reconciliatory comments about Turkey’s military operations.

While the United States remains concerned about many different and complicating factors involving Russia, Iran, Turkey, the Syrian government, the Syrian opposition, and the Kurds, what Secretary Tillerson has enunciated is an ambitious policy that lacks detailed steps to realize it. Most importantly, it neglects to specify how, in a military conflict, the US Department of Defense can deliver on its promises to help the Syrian opposition while Russia and Iran have already achieved sweeping control on the ground.