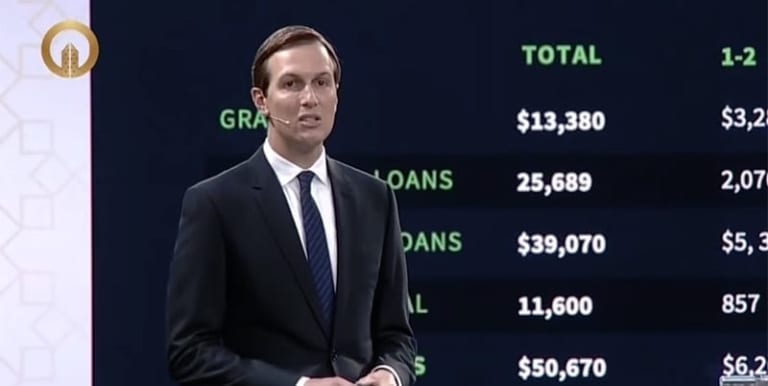

The Manama, Bahrain, economic meeting has wrapped up its two-day proceedings to advance the Trump Administration’s Peace to Prosperity: A New Vision for the Palestinian People and the Broader Middle East, whose ostensible aim was to help improve the economic conditions of the Palestinians. Jared Kushner, President Donald Trump’s son-in-law and special advisor, presented the plan at the meeting––dubbed a workshop––and urged the Palestinians to seriously consider it as a vehicle to unleash their potential, empower them economically, enhance their governance, and integrate them regionally. “Peace to Prosperity” promises $50 billion in grants, guaranteed loans, and private-sector investments over a 10-year period to help the Palestinian economy in the West Bank and Gaza and to assist neighboring countries Jordan, Lebanon, and Egypt.

Neither the plan nor the Bahrain meeting delved into the political aspects of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict nor did they address the next phase of the administration’s involvement in formulating a vision for peace. But “Peace to Prosperity” was designed to explore specifically the economic foundation for that long-sought peace, which would be pursued at a later phase after the next Israeli parliamentary elections scheduled for September 2019.

The Palestinian Authority rejected the plan outright and refused to attend the Manama meeting while Israel was not invited, although Israeli journalists were allowed to cover the proceedings. Regional countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Jordan, and Egypt were represented by either ministers of finance or lower-level officials. The Trump Administration was represented by Kushner, Secretary of the Treasury Steve Mnuchin, and other officials from the Department of State. Businesspeople, academics, and international personalities from the West Bank, the United States, Europe, and the Middle East attended the meeting.

Arab Center Washington DC asked its resident fellows to reflect on how the Manama meeting helped to serve or negatively affect the interests of a number of actors of central importance to the plan and those who participated in the workshop. Following are their responses.

Supremacist Outlook toward Palestinians

Tamara Kharroub

Aside from the absurdity of the agenda of the Bahrain conference, the cluelessness of the (mostly unknown) speakers, the abundance of empty rhetoric and lack of substance, and the meager consideration of the realities on the ground, the complete disregard for the Palestinian people––under the banner of helping Palestinians––was remarkable.

This supremacist outlook toward Palestinians by the Trump Administration’s peace team has been evident over the past two years. Most recently, Jared Kushner doubted whether Palestinians were able to govern themselves; Jason Greenblatt wrote an op-ed pontificating to the Palestinian people about what’s good for them and continues to regularly tweet hatred at Palestinians, parroting Israeli propaganda talking points and spreading false accusations. Meanwhile, the US ambassador to Israel, David Friedman, doubled down on his remarks that Israel has a “right” to annex parts of the West Bank (which is understood to mean a biblical right, given that Israel violates international law in its policies there). To add fuel to the fire, The New York Times recently published and promoted an op-ed by Israeli Ambassador to the UN Danny Dannon, in which he blatantly referred to Palestinians as a failed people and called for their “surrender” and “national suicide”—essentially the abolition of their national and cultural identity, which is also known as ethnic cleansing and cultural genocide. With this approach, it has become very clear that what the Trump Administration and Israel are after is not peace but the ultimate surrender of Palestinians and the complete elimination of the Palestinians’ human and political rights and their national project.

While much has been known and written about this team’s racist neocolonial arrogance, more condescending voices are emerging from among the Arab Gulf sponsors of the Bahrain conference. Palestinians have been squeezed into further compromises at least since Oslo and for the last 25 years, and in Bahrain, they are being told once again they could live a little better only if they surrender more of their rights. The fact that Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain are putting their weight behind policies and approaches that deprive Palestinians of their basic rights—and while scheming about the future of the Palestinian in their absence—is just as revealing of these Arab countries’ disregard for Palestinians.

The Palestinian response has been very clear and is supported by reports and expert analyses: economic peace alone does not work, economic development cannot precede the lifting of the occupation (its primary obstacle), and money cannot replace political and human rights. Some participants in the workshop made references to these issues. However, whatever the discourse, the reality is that the Palestinians are the most powerless entity in this picture, and although the “Peace to Prosperity” meeting was hailed as the first phase of the infamous peace deal, the political part of the plan is already well underway. Palestinians are feeling profoundly the dire and likely irreversible consequences of moving the US embassy to Jerusalem and declaring Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, liquidating the refugees’ right of return, and cutting funding to humanitarian and economic programs.

Israeli Gains in Bahrain

Khalil E. Jahshan

The issue of winners and losers from the Bahrain meeting will be debated for a long time to come. Israeli government officials were not invited to participate directly in Manama, but due to the refusal of the Palestinian Authority to attend, Israel nonetheless emerged as the main beneficiary of the conference. This was guaranteed in advance by manipulating the agenda to avoid any discussion of the Palestinians’ political aspirations and legitimate right to self-determination or to ending Israel’s 52-year-old military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. The Netanyahu government, fully confident with the pro-Israel position of the Trump Administration, was quite satisfied with the limited participation of its business community, academia and mainstream media.

The Israeli agenda was very clear and quite focused. It centered around Israel’s historic yearning for political normalization with Arab countries, particularly in the Gulf region, without making any significant or long-term commitments on Palestine. Israel’s logic is quite simple: peace with Arab countries is essentially transactional, while peace with the Palestinians centers around territorial compromise—a price Israel has not been willing to pay, and certainly not at this time. Israeli participants were very surprised and ecstatic about the warmth of the reception they received in Bahrain. The grand prize came in the form of the statements made by Bahrain’s Foreign Minister Khalid bin Ahmed Al Khalifa, who blamed the Palestinians for their absence and declared that “Israel is part of this heritage of this whole region, historically. So, the Jewish people have a place amongst us.” He expressed his country’s hope about the Manama workshop, “if we take this seriously … could be a very important game changer,” equating it to “Camp David and the late President Anwar Sadat.” These words, coming from an Arab official, were interpreted by many Israelis as not only a recognition of Israel as a state, but of its Jewish character as well.

The Arab Division about Palestine

Radwan Ziadeh

The Manama meeting was nothing special in the history of the Arab-Israeli and Palestinian-Israel conflict, like the 1991 Madrid peace conference, for example. But what we saw in Manama was another example of the divisions in the Arab world regarding the question of Palestine and the degree of its centrality to Arab affairs today. The Trump Administration has not only devised a plan for peace and advertised it but indeed imposed it on some Arab actors—such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, and Morocco—who attended the meeting, making them acquiesce in supporting the proceedings in Manama to preserve their relationship with the US administration. There are other Arab countries undergoing political transitions from authoritarianism whose representatives did not attend, despite their historical support of the Palestinian cause, including Syria, Algeria, Lebanon, and others. The Palestinians, obviously, were also absent.

The Manama conference will fail, like others before it, to resolve the Arab-Israel conflict because what is being proposed is below the threshold of what is acceptable for the Arabs regarding Palestine. One important question remains, however: what may reunify the Arabs after they united for the Madrid conference, opposed Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s policies against Palestinians, and rejected President Trump’s decision to declare Jerusalem the capital of Israel and move the American embassy there? The Arabs today are incapable of making a unified stand on the Kushner plan, which has not even been considered by the League of Arab States. Finally, it is important to emphasize that those in attendance in Manama were there because they were more concerned about being on Trump’s good side than because of their ardent belief in the peace plan he is proposing to resolve the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

The Glaring Absence of Principal American Decision-Makers

Joe Macaron

The first remarkable feature of the workshop in Manama was the absence of US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and career diplomats who have prior experience in conflict resolution. Instead, this initiative was orchestrated by a handful of inexperienced policy-makers. Interestingly, at the same time of the conference Secretary Pompeo was visiting Gulf states to discuss Iranian threats and White House National Security Advisor John Bolton was in Jerusalem holding talks with Russian and Israeli colleagues on how to deter Iran in Syria. This division of labor reflects the larger context of the United States’ central objectives in the Middle East: an Arab-Israeli alliance to counter Iranian influence.

The White House was successful in pulling off this workshop by enforcing its agenda on Arab leaders who recently have been reluctant to embrace this controversial US initiative. Resolving the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, however, was merely the sideshow. The lasting American impact in Manama is the convening of the largest display of Arab-Israeli normalization before achieving a purported peace. US pressure on Arab leaders to host and attend this workshop was successful; however, it might backfire down the road if Palestinians were forced to accept a deal that is not in their best interests.

This workshop will test the United States’ influence in resolving a conflict with many layers of complexity. Offering an economic portion of a peace plan without a political vision is a recipe for failure. In the long term, the Trump Administration is undermining the major parameters of the US role in the Middle East peace process. The timing of the workshop coincided with unprecedented levels of US-Iranian tensions and the start of the American presidential elections season. Both could provide major distractions from this initiative. By pursuing conflicting objectives, the Trump Administration might ultimately come up short both in achieving peace between Israelis and Palestinians and in forming a coherent Arab-Israeli alliance against Iran.

How Did the US Congress React?

Marcus Montgomery

The most remarkable reaction from Congress to Kushner’s “Peace to Prosperity” meeting has been US lawmakers’ near universal silence. Congressional members’ reluctance to weigh in on the event is not necessarily surprising, however. For some time now, lawmakers have been skeptical of Kushner’s proposal because, even for Israel’s strongest supporters on Capitol Hill, early glimpses of the plan have looked like a death knell for the two-state solution.

In early June, just weeks after the administration announced its intention to unveil the economic segment of its plan, a bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced a resolution supporting the two-state solution and a bill setting up a “peace fund” that would provide economic support to the Palestinians. This was clearly a way to signal to the Trump Administration that individual members of Congress were not confident in Kushner’s plan, particularly because Kushner and his partner in the process, Jason Greenblatt, have been decisively vague on the potential political elements of their plan.

So, now that Kushner and company have completed the Manama workshop—with no references to the Israeli occupation, the blockade of the Gaza Strip, the obstacles of illegal settlements, or any semblance of a political solution to the conflict—lawmakers have little reason to believe that their concerns were not well founded. Even Senator Lindsey Graham, a staunch supporter of both Israel and President Donald Trump, delivered a half-hearted endorsement of the event. If Graham’s sentiment is any indication, members of Congress saw the Manama meeting as nothing more than a way to jumpstart new discussions about, and generate new ideas for, solutions to the conflict. That is hardly the ringing endorsement one might expect for a grandiose strategy being billed as the “deal of the century.”