Throughout the Arab world, there have been numerous protests, uprisings, and challenges to the painful policies that come with an International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan arrangement. Most notably were the bread riots of the 1970s through the 1990s in Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia protesting IMF loan conditions requiring the removal of bread subsidies. Many protests against IMF loans also preceded the Arab Spring, whose rallies were also a clear articulation of societal frustration with governments’ economic policy choices. Indeed, the Arab Spring protests saw the Arab people call for a break with decades of corruption, poverty, chronic unemployment, and social injustice. Among protesters’ many demands were accountable governments, economic growth and prosperity, and a wider, more equitable distribution of wealth. As many of the Arab people continue to feel alienated from their governments’ attempts to deliver on economic prosperity, Arab countries signing IMF loans have to anticipate negative societal responses to the austerity policies that come with any agreement made with the institution, policies such as a reduction in social spending and subsidies and limits on public sector employment.

The IMF and the Washington Consensus

Countries come to the IMF, what is known as a “lender of last resort”, when they have run out of options to borrow from domestic or international capital markets. In exchange for loans with very low interest rates, the IMF asks countries to institute painful economic reform policies—a practice called conditionality—that aim to cut government expenses and raise revenue so that countries can pay the IMF back relatively quickly. In some cases, these loans are to be paid back in as little as 3 to 5 years. Historically, the IMF prescribed policy reforms to debtors that were influenced by neoliberal economic ideas reifying the importance of markets and the removal of subsidies on food and energy, and include both the removal of statist policies such as import substitution or tariffs—that protect domestic industries and impede imports—and the promotion of individual entrepreneurship and private sector employment to discourage people from seeking employment in a bloated public sector. This constellation of ideas is broadly referred to as the Washington Consensus.

After decades of criticism from emerging market economies and civil society groups, changes have been made to IMF conditionality that have moved the Fund away from prescribing a one-size-fits-all approach to conditionality.

For many critics, the Washington Consensus amounted to the deindustrialization of developing countries, driven by “market fundamentalism” and an intrusion into the public policy autonomy of debtor countries. After decades of criticism from emerging market economies and civil society groups, changes have been made to IMF conditionality that have moved the Fund away from prescribing a one-size-fits-all approach to conditionality. The European debt crisis, the Asian financial crisis, and international financial organizations’ failure to predict and to warn about the 2007–2008 financial crisis also raised further external criticism of the IMF from many of its more powerful member countries.

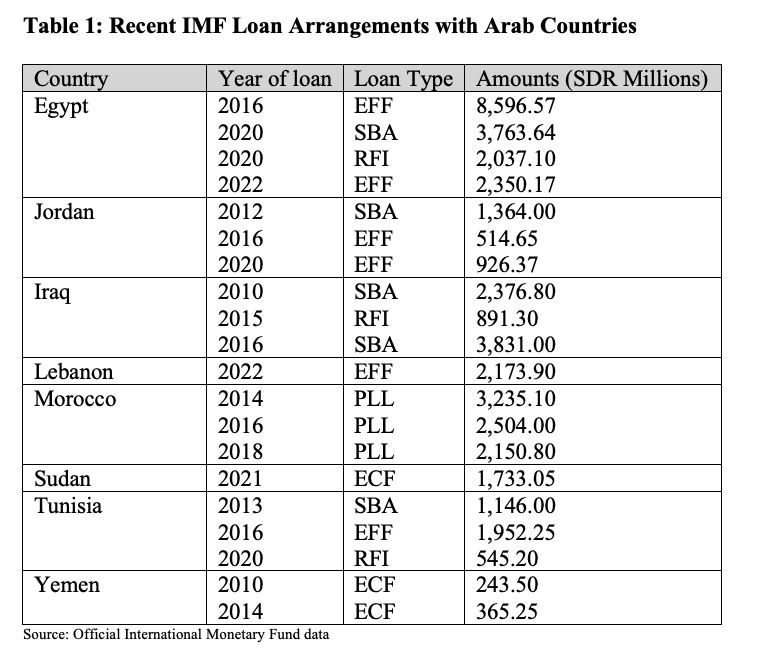

The IMF has different types of loans whose conditions vary based on two broad loan categories: “non-concessional” and “concessional” loans. Non-concessional loans include the Stand-By Arrangement (SBA), the Extended Fund Facility (EFF), the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI), the Flexible Credit Line (FCL), and the Precautionary and Liquidity Line (PLL). Most Arab countries in the past decade have borrowed in the non-concessional lending category, which is designed for countries with short-term balance of payments crises. Both SBAs and EFFs include specific macroeconomic targets as conditions that are designed to correct the imbalance in question. Lasting 1 to 2 years and meant to be repaid in 3 to 5 years, SBAs often contain stipulations designed to reform “structural” issues such as governance and legal frameworks that the IMF claims undermine macroeconomic stability and subsequent growth. Similarly, the EFF is designed for debtors with structural issues that chronically undermine economic growth and produce balance of payments issues. Differentiating between the two, EFF loans focus more on addressing deeper institutional and governance reforms than SBAs do, and last from 3 to 4 years with a repayment period falling between 4.5 and 10 years.

IMF Loans and Macrocriticality

Over time, the IMF has tried to counter ill feelings among debtors through a reduction in structural conditions, a focus on policy flexibility, and government participation in program design. The IMF’s conditions have shifted away from mandating trade reform policies and asking for the privatization of state-owned enterprises, moving instead toward tax policy and financial sector reform. Hence, the emphasis today is on fiscal consolidation, which involves cutting costs and raising state revenues by increasing sales and income taxes. The IMF has evolved, noting that it would expand its own understanding of “macrocriticality”—those policies that impact economic growth and macroeconomic stability—and design its loan agreements accordingly. This means that the IMF has started to recognize that corruption, gender, inequality, and climate change all have macrocritical impacts on a country’s economic health.

While these recent changes to conditionality are deemed to be less intrusive than the Washington Consensus period of the 1990s, it remains challenging for governments to get their house in order in just a few short years.

While these recent changes to conditionality are deemed to be less intrusive than the Washington Consensus period of the 1990s, it remains challenging for governments to get their house in order in just a few short years. In addition to loan conditionality, countries can be asked to implement preconditions for funding so as to build the IMF’s confidence in their governments’ commitment to reform, which means that hardship sometimes also precedes IMF funding. Moreover, throughout a given loan arrangement period, IMF staff continue to monitor debtors to ensure that they are on track to repay their loans. These practices can feel intrusive and undermine the perceived sovereignty of states. Moreover, all loan agreements must get approval from the IMF’s executive board, where countries like the United States have strong political oversight of loan programs, and can potentially bring in non-technical considerations that many member countries find intrusive or further challenging.

In recent years, there has certainly been more emphasis in loan agreements on both inclusive growth and the social protection of the poorest members of society, ensuring that those most vulnerable in a debtor country are not hurt by the economic adjustments of conditionality. That said, these efforts have not eliminated the hardship that people experience as a result of their countries’ needing to swallow the painful pill of economic austerity in order to comply with IMF conditionality. While the IMF can take credit for improving debtor countries’ balance of payments, the same cannot be said for their levels of inflation, growth, inequality, and poverty.

On the important issue of economic growth, studies have shown that most of the countries that have taken loans from the IMF experienced reduced economic output in the short term. Other studies also point to worsening inequality when states borrow from the IMF. Countries that participated in IMF programs also saw an increase in poverty, with more people slipping below the poverty line after an IMF program was initiated. The socioeconomic impact of concessionary lending, meanwhile, is somewhat less pessimistic. There are some studies that show a statistically significant positive relationship between economic growth and concessionary lending to low income countries (LICs). Other studies have also noted that LICs that took IMF loans had more rapid reductions in inequality and poverty, increased social spending, and decreased infant mortality than LICs that did not borrow from the IMF. This data could be explained by the IMF’s having, in some cases, mandated increases in health and education spending.

The IMF, the Arab World, and the Arab Spring

The Arab Spring was a “moment of truth” for the IMF, during which it further reconsidered its views and policies on the social impact of its loans. Specifically, the Arab Spring altered the IMF staff’s perspective on its economic advice and conditionality in Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia. IMF conditionality was thereafter visibly changed in three areas: promoting more inclusive growth to protect the poorest in society; advancing the case to enhance economic redistribution and prevent further inequality through the provision of a social safety net; and strengthening health and education spending as important antecedents to economic growth.

Reviews of IMF staff reports and news articles, as well as interviews with the organization’s staff, demonstrate that the IMF has changed its language, policy prescriptions, and viewpoints in reaction to the Arab Spring protests and uprisings. In a speech made in December 2011—almost a full year after the start of the Arab Spring—then IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde noted that the IMF “learned some important lessons from the Arab Spring. While the top-line economic numbers—on growth, for example—often looked good, too many people were being left out.” Similar statements noting a change in the IMF’s approach to conditionality after the Arab Spring have also come from many others among the organization’s staff and management.

Nevertheless, the IMF still insists on governments’ responsibility to put their financial house in order, even though such actions might still cause hardship. In Jordan’s 2016 IMF Extended Fund Facility loan, for example, fiscal consolidation conditions included removing subsidies on bread and other basic commodities, causing their prices to rise steeply. The agreement also ushered in a 16 percent value-added tax (VAT) on most goods and services, causing a great deal of hardship for vulnerable people and communities. In the Jordanian government’s 2018 reform of its income tax laws in response to IMF loan conditions to increase revenue, a controversial law was also introduced that effectively shielded members of parliament and other politicians from sharing the burden. Moreover, the new tax law was set to lower the threshold of taxable income from $34,000 to $22,500 for a family and from $17,000 to $11,200 for individuals. Frustrations with these laws peaked during protests that took place across Jordan that summer, with demonstrators decrying rising taxes and the lack of a return on social services. A key aspect of Jordanian protesters’ aggravations was the growing perception of corruption and rent-seeking behavior from crony capitalists who were seen as remaining unhurt by IMF-imposed adjustment costs.

For Egypt’s 2016 EFF loan, the IMF required reforms (some of which were demanded prior to disbursal) included exchange rate liberalization, which effectively brought on a substantial devaluation of the Egyptian pound. Conditions also comprised the Egyptian government’s reduction of public debt by shifting to targeted subsidies on fuel through the distribution of smart cards, which limited the number of subsidized items for purchase by each household. To increase government revenue, the Egyptian government also introduced a 13 percent VAT. At the same time, the country’s top income tax bracket was reduced from 25 to 22.5 percent, effectively giving a tax break to Egypt’s elite. Although the loan conditions did include expanding spending on vulnerable families with disabled children and on the elderly poor, corruption and fraud have nevertheless plagued Egypt’s smart card system. Theoretically this should be a progressive policy; but based on feedback from civil society groups, many of Egypt’s very poorest are illiterate and undocumented, which often means they cannot or do not apply for these smart cards. In addition, structural reforms included streamlining industrial licensing, providing financing to small and medium enterprises, decriminalizing insolvency, and simplifying bankruptcy laws, all in an effort to spur more private and foreign investment.

Although the loan conditions did include expanding spending on vulnerable families with disabled children and on the elderly poor, corruption and fraud have nevertheless plagued Egypt’s smart card system.

Far less utilized by Arab countries are the IMF’s “concessional” loans, which are characterized by lower interest rates and longer repayment periods than non-concessional loans, and are reserved for the very poorest countries. Yemen and Sudan, for example, have both taken concessional loans, utilizing the IMF’s Extended Credit Facility (ECF), which is reserved for LICs with long-standing balance of payments problems, and which provides 3 to 4 year loans with zero interest rates and a 5.5-year grace period. Concessionary loans are tied to a broader strategy focused on poverty reduction. The IMF formally stipulates that ECF lending must be supported by a country-owned poverty reduction and growth strategy, as well as by support policies that safeguard social spending, including “expenditure floors.” Oxfam has noted that the IMF also has placed more emphasis on social protection measures in concessional loans, such as preserving financial transfer payments like pensions, food security plans, and unemployment insurance payments. But more needs to be done to protect the most vulnerable. For example, in Sudan’s 2021 EFC loan, conditions included removing energy subsidies, improving banking laws to make the situation easier for private sector investors, and expanding and modernizing tax collection authorities’ remittance capabilities.

The Need to Address Other Ills

The IMF has been blamed for many of the economic, political, and social ills that plague its debtor countries. However, the empirical and academic challenges of testing whether IMF loans have made a country better or worse off are numerous. After all, most debtor countries were already undergoing difficult economic times before receiving IMF financing. Moreover, no economic models are available to accurately perform such a comparison, and comparable countries are not always available so that one can carry out rigorous control studies. Nevertheless, the economic pain of adjustments required by IMF loan conditionality should not be ignored or minimized.

Most debtor countries were already undergoing difficult economic times before receiving IMF financing. Nevertheless, the economic pain of adjustments required by IMF loan conditionality should not be ignored or minimized.

It must be said that the IMF is often dealing with debtor countries that are highly corrupt and undemocratic, and perceptions of corruption in Arab countries are among the highest in the world. People will understandably protest fiscal consolidation policies of cutting costs and raising taxes if they already believe that their governments are corrupt, mismanage the public purse, and are opaque regarding their spending. In recent years, the IMF has changed its emphasis to include more social protections and macrocritical loan conditions. Some have suggested that this is merely rhetorical support for inclusive growth and nothing more. But it might be better to note that loan conditionality can have its own unintended consequences in corrupt societies where governments strategically shift the burden of adjustment onto their weakest and most vulnerable citizens. Regardless of whether the IMF or corrupt governments are to blame, people will protest these austerity policies when facing economic hardships. And the Arab world has plenty of experience in protesting perceived economic injustices.

Featured image credit: Shutterstock/Tada Images