The Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping present a new phenomenon in geo-economic conflict: a non-state actor using asymmetric warfare not just to fight conventional armed forces, but to also impose targeted economic sanctions by selectively attacking international shipping. The Houthis have made this leap by combining two factors: inexpensive and high-tech weaponry that can threaten—even sink—oceangoing ships and control over strategic coastal territory overlooking one of the world’s busiest maritime chokepoints: the Bab al-Mandab Strait. Scores of incidents have damaged three dozen ships as of late March, a result that the Iran-friendly Houthis describe as retaliation for the Israeli bombardment and blockade of Gaza starting last October. The Iran-backed group says it aims to increase international pressure on Israel to halt its Gaza offensive.

The siege on Red Sea shipping has re-oriented trade between Asia and Europe in an uneven way. Shipping firms based in countries where governments have spoken out against the Israeli offensive in Gaza have received exemptions from Houthi attacks, resulting in cost advantages and higher profits. Conversely, shippers based in countries supporting Israel, along with those carrying Europe- or US-bound cargoes, have lost access to the Red Sea shortcut between Asia and Europe. As a result, cost and voyage duration have increased together with demand for vessels, which helped push up cargo fees, including on routes that do not travel via the Red Sea.

The skewed disruption to global shipping suggests that the Houthis have succeeded in meeting their objective of imposing costs on supporters of Israel, although the anti-ship campaign has not had a noticeable effect on Israel’s offensive in Gaza. Houthi leaders have reportedly cemented competitive advantages for Chinese and Russian shippers by providing free Red Sea passage with guarantees against attack in exchange for yet-unspecified diplomatic support. The selective strategy employed by the Houthis is imposing economic penalties resembling economic sanctions that disproportionately affect EU-based firms as well as Egypt, which is losing Suez Canal transit fees due to shipping detours around the southern tip of Africa. Indeed, the added supply chain costs are weighing heavily on already pessimistic economic forecasts for the European Union and Egypt. The longer the attacks continue, the greater the residual impact, dampening the prospects for growth.

The Houthi campaign in the Red Sea has produced a new form of global economic disruption.

Moreover, the Houthi campaign in the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea has produced a new form of global economic disruption based on grievances with Israel, and is proving difficult to deter or counter. The campaign is similar to the 1973 Arab oil embargo in seeking to inflict economic damage on wartime supporters of Israel. But the 1973 embargo, which tripled global oil prices nearly overnight, offered no exemptions for countries friendly to the Arab cause. The Houthis are able to provide such exemptions by leveraging vessels’ automated messaging systems and registry details to distinguish between “targetable” ships and “friendly” vessels that should be allowed to transit unmolested. The strategy unfolding along the Yemeni coast poses new and worrisome confrontation with global norms such as freedom of navigation and access to the global commons.

As a result, the Houthis have managed to win the admiration of many in the Global South, and citizens of Arab and Muslim states in particular. The Houthi campaign has also exposed ineffective countermeasures by the United States and its NATO allies as well as inaction by Arab governments and regional organizations that have so far failed to impose costs upon Israel or its backers in the United States and Europe.

Can the Houthis Be Deterred?

The list of victims in Houthi attacks and responses is growing. Killed in the attacks thus far have been three sailors on the Barbados-flagged True Confidence, a cargo ship in the Gulf of Aden, along with two US marines drowned in a related vessel boarding, and at least 34 Yemenis who died amid various American-British airstrikes. One Israel-linked ship, the Galaxy Leader, remained impounded in Yemen at the time of writing, along with its 25-member crew. Another victim, the Belize-flagged Rubymar, was hit by a Houthi missile and sunk in the Red Sea.

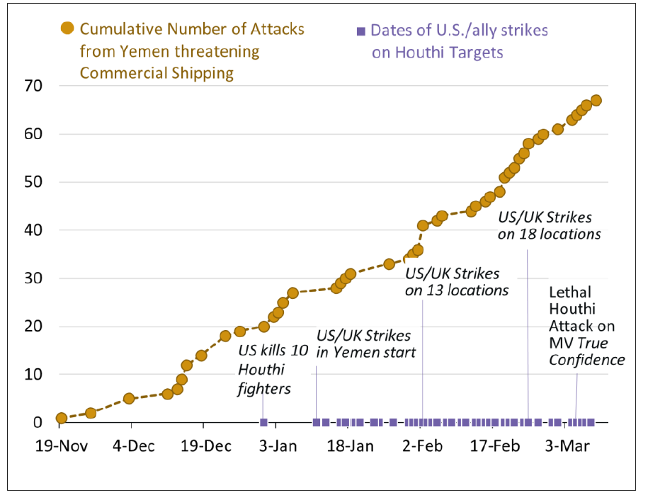

Countermeasures launched thus far have degraded Houthi weapons stocks and capabilities but have failed to deter attacks on shipping. Measures include several rounds of US-UK airstrikes on Houthi sites across Yemen and aerial defenses that have knocked down attack drones and missiles, a significant US-led multinational naval presence (Operation Prosperity Guardian), and even a UN Security Council resolution condemning the attacks and insisting on rights of states to defend their vessels. US and British attacks on Houthi sites inside Yemen have created new grievances and a rationale for a potential extension of the Red Sea attacks beyond a ceasefire in Gaza. As shown in Fig. 1 below, Houthi attacks on shipping actually intensified after the onset of US-UK retaliatory strikes.

Figure 1: Maritime incidents and responses as of March 12, 2024. Source: CRS, using US government statements and media reports. Note: Attack incidents involving multiple targets may be considered a single incident. Data is approximate and subject to revision.

The lack of success of the US-UK military response may have created the impetus for direct talks with the Houthis and indirect US-Iran talks held in Oman that have yet to deter the anti-ship campaign. Although Iran supports the Houthis—and the group’s leadership shares many of Tehran’s goals—the Yemeni militants are largely autonomous and could resist Iranian entreaties to stand down, although it is not clear that such demands from Tehran have been forthcoming. Iran-backed militias in Iraq and Syria did hold their fire after the United States retaliated in Iraq and Syria for the deaths of three American troops in a January 28 attack on Tower 22, a small US base in Jordan. Meanwhile, as Fig. 1 shows, the Houthi attacks did not decline in similar fashion.

The Houthi movement has demonstrated since the launch of its 2004 offensive to take the Yemeni capital Sanaa that the group is not particularly cautious, casualty-averse, or susceptible to typical military deterrence. Houthi weaponry is simple and orders of magnitude cheaper than weapons used by the US-led naval coalition countering them. Much of the group’s hardware is assembled locally in Yemen. Countering budget drones and submersibles has become increasingly costly for western militaries. Crewmembers on a US warship in the Red Sea told the BBC that the US Navy had not come under such consistent hostile fire since World War II.

Inside Yemen, the Houthis have leveraged the popularity of the attacks to gain hard and soft power, recruiting thousands of new fighters attracted by favorable publicity across the Muslim world. The emboldened militant group announced on March 14 that it would extend attacks beyond the immediate Bab al-Mandab area to the broader Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean to target Israel- and allied-linked shipping diverted via the Cape of Good Hope. As of the time of writing, no attacks along this alternative route have been reported.

Perverse Incentives

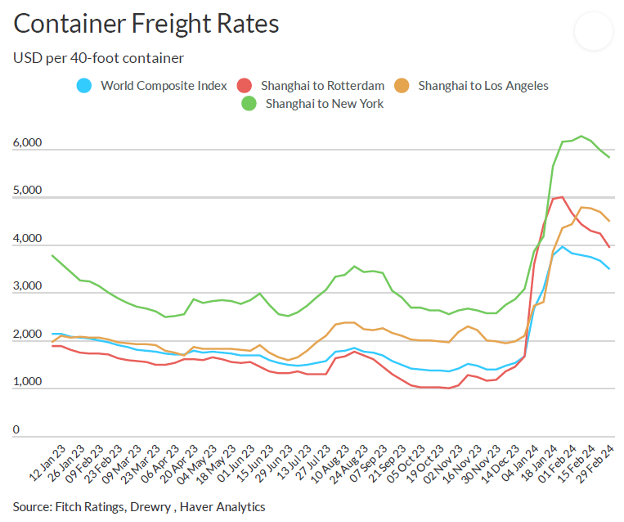

Meanwhile, some shipping firms are profiting from the chaos, according to a report and author conversations with the ratings agency Fitch. For example, costs to European, American, and some Asian firms re-routing around the Cape of Good Hope on the way to and from Asia have increased by around 50 percent. But shipping rates on Asia-Europe routes have increased by almost 300 percent, enhancing profits for firms taking either route (see Fig. 2). But the biggest recipients of these rate increases are shipping firms able to continue transiting the Red Sea and avoiding the long African detour.

Figure 2: Shipping costs tabulated by World Container Index depict costs rising by 151 percent since early October. The most affected routes, those between Asia and Europe, have seen rates increase by 284 percent.

Several factors are behind the rate increases. First, the costs associated with longer transits for ships traveling via the Cape of Good Hope are higher. Second, those longer journeys are removing shipping capacity from the market, resulting in a nearly 10 percent jump in vessel demand, along with higher rates in what would otherwise be a slumping market. Third, some shippers still using the Suez Canal face higher costs in the form of spiking insurance and security costs—especially for onboard security personnel—and increased hazard wages for seamen facing new risks.

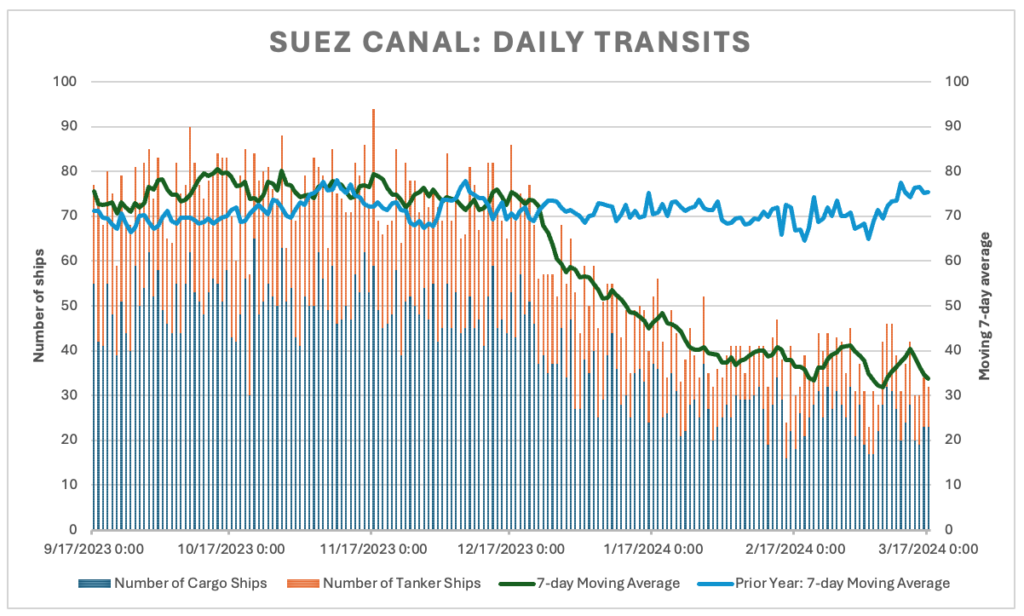

IMF data show transits through the Suez Canal declining by more than half in recent weeks.

The combined effect is making the Asia-Europe route more attractive, albeit more dangerous, especially to firms that can charge higher rates while avoiding the southerly detour around the Cape of Good Hope. The alleged Houthi transit “guarantees” to Russian and Chinese shippers may have widened cost disparities. Various reports have shown that higher profits on the Asia-Europe route has attracted Chinese firms to shift into the trade based on preferential access to the Red Sea.

One potential impediment for the restoration of free navigation is whether higher profits provide a perverse incentive to governments to protect their firms’ competitive advantage by refraining from diplomacy aimed at halting Houthi attacks. According to Fitch, de-escalation in the Middle East and a return of transit to the Suez Canal are likely to reverse the increased shipping rates and reimpose fair competition among shipping firms.

Big Shifts in Global Shipping

Transits through the Suez Canal are among those most affected. Prior to the Houthi campaign, the canal hosted 12 percent of global sea trade, including a 30 percent share of container vessels. The canal linking the Mediterranean and Red seas is also one of the most important strategic chokepoints affecting the energy commodity trade. Some 15 percent of globally shipped goods, including crude oil and refined products, pass through the canal which is an essential source of income for Egypt.

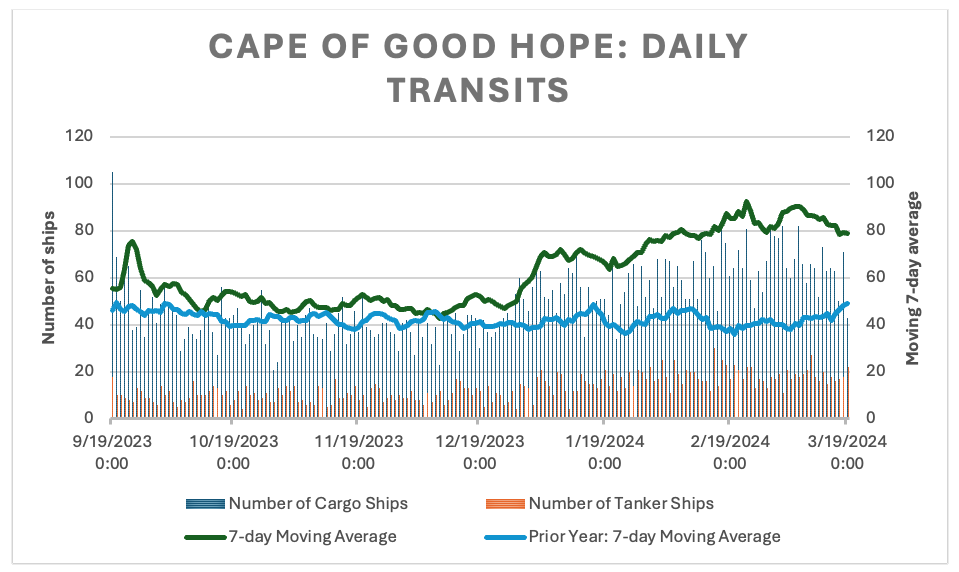

As the Houthi attacks approach the six-month mark, International Monetary Fund data show transits through the Suez Canal declining from a weekly average of 74 ships in 2023 to about 35 (more than half) in recent weeks (see Fig. 3). Simultaneously, transits around the Cape of Good Hope are up by a nearly similar amount in the same period (see Fig. 4).

Figure 3: Suez Canal transits are at less than half their normal levels (Source: Author, using data from IMF PortWatch, March 19, 2024)

Figure 4: Cape of Good Hope transits are double their normal levels (Source: Author, using data from IMF PortWatch, March 22, 2024)

These figures hide multiple disparities:

- Most or all container ship voyages by Denmark’s Maersk, Israel’s ZIM, Japan’s Mitsui OSK, Swedish-Norwegian Wallenius Wilhemsen and others have routed around southern Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, while France’s CMA CGM said in March that it was rerouting on a case-by-case

- All Qatari LNG shipments to Europe have been forced to detour south around Africa, with the last LNG transit of the Red Sea taking place in mid-January. The diversions of LNG ships and their supercooled cargo may have more to do with safety—relating to the potential harm and expense from an attack—than with any Israel connection.

- Some Chinese COSCO container ships were reported passing unobstructed as recently as early March, while others avoided the Red Sea. Taiwan’s Evergreen was continuing to offer Red Sea services but via subcontractors.

- Smaller Chinese shipping firms were taking advantage of higher rates and offering new services through the Red Sea. China United Lines in March launched a Red Sea Express service between Chinese and Red Sea ports, and other niche operators have made similar moves to capitalize on higher rates, including a Singapore-based carrier and another in Oman.

Meanwhile, crude oil shipments from Saudi Arabia to Europe were at higher levels than normal, with the exception of a brief spike during the 2020 price war. The jump in shipments is possible because Saudi Arabia operates oil export terminals on its own Red Sea coast—well north of Houthi-controlled Yemeni territory—which allows it to send crude oil cargoes unmolested through the Suez Canal to Europe and beyond.

Policy Recommendations

The Houthi ultimatum notwithstanding, a ceasefire agreement in Gaza offers the most appealing route to ending the attacks. A full ceasefire and release of Israeli hostages and Palestinian prisoners are near-universal goals at this point. The expanding human catastrophe in Gaza may eventually overcome the formidable barriers to exercising American leverage over Israel to reduce some of its ceasefire demands. A halt to the Houthi attacks may therefore serve as an additional positive outcome of a ceasefire, along with numerous others such as return of hostages and resumption of aid shipments to Gaza.

However, a Gaza ceasefire alone may not be sufficient to halt the Houthi attacks and restore free navigation in the Red Sea and Bab al-Mandab. Houthi grievances extend to the states launching counterattacks on their weapons sites. The group may also be loath to lose the international media attention that appears to be assisting with its longstanding goal of consolidating domestic power. Further pressure is likely to be needed, perhaps through a resumption of diplomatic conversations or economic pressure on Houthi benefactors in Iran.

Finally, China may seek to mediate an end to the attacks. As a major export-oriented economy seeking to maintain access to global markets, China’s exposure to increasing shipping costs is high. Any sign of weakening demand—or substitution—for Chinese goods would probably elicit a strong response from Beijing.

Conclusion

The shipping attacks by Yemen’s Houthi represent a new and novel form of exploiting deep international divisions on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The selective campaign has created a skewed disruption of global trade between Asia and Europe, while causing an increasing level of physical damage and a few deaths. The Houthi attacks have brought about expensive detours and additional costs for shippers based in countries with links to Israel. Meanwhile, firms from nonaligned countries have benefited from Houthi targeting discrimination to effectively maintain profit-enhancing access to the Red Sea.

The Houthi practice of distinguishing targets by country of origin or ownership serves as a new and unfamiliar form of targeted economic sanctions by a nonstate actor, based on a political grievance. Most alarmingly, the Houthi strategy has succeeded in undermining longstanding institutional norms around oversight roles of the great powers and freedom of maritime navigation. As such, the Red Sea attacks could serve to inspire copycat actions by other groups with similar grievances. However, it appears that few actors can combine the asymmetric advantage of strategic geography—including control over territory adjacent to a vital maritime chokepoint—with access to inexpensive and sophisticated weaponry.

The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

Featured image credit: Shutterstock/Dipix