The current GCC crisis has seen a significant employment of media technologies as tools of conflict and influence. Media and communications platforms were used to launch a negative public relations campaign against Qatar, such as the attacks by Saudi, Emirati, and Egyptian television networks aimed at painting Qatar as a threat to regional stability. The blockading countries, especially Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain, also used social media platforms to identify their own citizens who expressed sympathy with Qatar and arrested them based on their views and online activities, in direct violation of freedom of expression. Additionally, the 13 demands leveled at Qatar included demands to shut down media organizations, and this violates freedom of the press.

Most recently, new reports and investigations have revealed that the United Arab Emirates was behind the hack of the Qatar News Agency and the false statements broadcast on the site. This was a perilous move intended to legitimize the conflict and the blockade against Qatar, where communications technologies were brazenly used as instruments of warfare.

During the last few years, it was predicted that the year 2017 would be the year of cyber warfare. The GCC crisis presents a prominent example of this, demonstrating both the dangers and the implications of such efforts. Most visibly, the GCC crisis and other recent events reveal a new trend in global political dynamics: the replacement of military and soft power with a rapidly emerging “cyber power.”

Hacking and the Move to Cyber Power

The year 2017 has so far produced several signs of a new era of global politics and competitions for power. For example, during the 2016 presidential elections in the United States, it was reported that hacks were perpetrated by Russia to influence the results, whether it was the hacking of the Democratic National Committee and email leaks or of state voter registration systems. With the reports of Russian hacking of US elections, the cold war has taken a new turn. Russia has also used several cyber tactics against Ukraine including espionage, denial of service attacks, leaks, and disruption of government communication networks, among others.

Cyberattacks introduce threats and damage in the real world on many levels—not only threats to individuals and states in the political sphere, but also economic threats to businesses and the world order. A report by Lloyd’s of London estimated that economic losses from a global cyberattack could be up to $53 billion. In fact, following the WannaCry global ransomware attack in May 2017, which was based on a vulnerability in Windows discovered and kept secret by the US National Intelligence Agency, many analysts echoed Microsoft’s call for a “Digital Geneva Convention” to protect against cyberattacks.

When considering the recent GCC crisis, it is clear that cyber operations played a significant role in the development of events. According to an investigation by the Qatari interior ministry, the UAE was responsible for the hack. The investigation confirms that the attacks started one month before the actual rift became public, when malware was planted in the Qatari state’s news agency website on April 19 and all accounts and password information were obtained and shared with another person through Skype.

The evidence presented by the Qatari investigation team shows that shortly after midnight on May 24, two Internet Protocol (IP) addresses originating from the UAE had increased traffic to the Qatar News Agency (QNA) website minutes before false statements were broadcast by the agency, attributing fake remarks to the Emir of Qatar Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani purportedly expressing support for Iran, Hamas, Hezbollah, and Israel, and suggesting that US President Donald Trump would not stay in power. Almost immediately after the false statements were made public, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates led an aggressive media campaign against Qatar as if the content and the campaign had already been planned in advance, according to the Qatari investigation team.

While the actual hack by an iPhone device could have come from a contracted third party anywhere in the world, the drastic increase in traffic from the two IP addresses in the UAE indicates that it was an attempt to confirm the hack was successful through repeated refreshing of the page. Interior ministry officials also stated that these two IP addresses did not visit the site before or after the incident, and that the advanced skills portrayed in the hack signal that a government entity was involved.

The investigation by Qatar’s Ministry of Interior is not the only source of evidence. Soon after the cyberattack on QNA, it was reported that a team from the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) traveled to Doha on May 26 to assist the Qatari interior ministry in the investigation. The FBI then confirmed that QNA was hacked. Although the FBI did not comment on the results of the investigation or its role in it as of late, the Washington Post reported a few days before the Qatari press conference that US intelligence agencies believed the UAE was behind the hack. New information collected by these agencies confirmed that on May 23, before the false statements were posted, senior Emirati officials had discussed the design and implementation of the hacking operation.

This premeditated event was essentially the spark triggering the GCC crisis, providing fodder for the Saudi-Emirati coalition to launch attacks, accusations, and a blockade against Qatar. The timing and content of the hack are very significant as it came only two days after President Trump’s visit to the region and his statements focusing on countering violent extremism and Iran’s influence. This is an indication that the hack was a deliberate attempt to portray Qatar as a threat to US interests in the region, which President Trump had emphasized. In this regard, it appears that the hack was a deliberate effort to legitimize and justify attacks against Qatar and to trigger the crisis that followed.

The deliberate nature of this move is significant, as it can be considered an act of war. While this was not the first time in history when media and communications tools were used to legitimize conflicts and pursue public influence for political ends, the developments in technology have enabled more substantial influence and easier access.

During World War I, a series of war propaganda posters were used in the United States to garner support among Americans for the war. From the “I want you for the US army” poster to “Wake up America,” “Buy a liberty bond,” and “Step into your place,” these posters were widely publicized and are believed to have sold the war to the American people. This was achieved through simple print technology, which played an instrumental role in gaining public support for US involvement in the war.

Several decades later, in 1964, advancements in technology presented audiovisual capabilities and broadcast television, when Lyndon B. Johnson’s presidential campaign placed the “daisy” advertisement on TV. The daisy ad made use of audiovisual technology to portray a dramatic image of a little girl facing nuclear explosions and subsequently elicit emotion and incite fear among Americans of Johnson’s opponent Barry Goldwater’s potential to start a nuclear war. The ad became controversial and was taken off the air. Although it aired only once, it is believed to have significantly contributed to LBJ’s landslide victory in the elections. In this case, the technology enabled more powerful, dramatic, and emotional content that influenced public opinion.

In 2017, media and communications technologies have evolved rapidly and drastically and have enabled cyberattacks, which are far more dangerous. The hack by the UAE as a deliberate attack on a state, using computer technology for strategic political purposes, is clearly part of cyber warfare operations.

In this regard, technology presented a new domain for influence and control. For most of the 20th century, hard power and military actions were the preferred means of control, as domains of influence were limited to physical spaces such as land, sea, and aerospace. Unlike attaining power by force, the last few decades of the 20th century saw soft power measures arise as the primary tools of influence and control, and these depend on the domains of persuasion and education.

Today, a new power has emerged, “cyber power,” to achieve control and influence, this time through coercion rather than by physical force or persuasion. In contrast to military and soft powers that require significant monetary and logistical resources, cyber power entails minimal resources and can be controlled by private individuals—even teenagers—with technical skills, to incur global widespread damage in a matter of seconds. With the evolution of the cyber domain of influence, both state and non-state actors can exert and exact control over other states and entities.

Following the release of the findings of the Qatari investigation and reports by US intelligence agencies, Saudi Arabia and the UAE launched a renewed and heightened propaganda campaign against Qatar. While the crisis was intended as a PR campaign of manufactured claims with the aim of ostracizing and isolating Qatar in the international community to coerce it to align itself with Saudi agendas, the plan backfired. The absurdity and illegality of claims, demands, and methods used almost had a reverse effect for the Saudi-Emirati bloc. Finding themselves in the middle of their own PR crisis, official Saudi and Emirati institutions increased their media activities and investments this week, with internationally-directed English-language materials disseminated widely through popular mainstream media outlets and social media platforms. The campaign continues to focus on alleged Qatari financing of terrorism, albeit without providing any evidence and despite the recent signing of the Memorandum of Understanding between Qatar and the United States on combatting terrorism and its financing.

The future will likely bring more advanced cyberattacks, and communications platforms will be highly employed as tools of warfare. Russia has so far shown its investments and focus on cyber power, but many more will follow. If such actions of warfare by Russia and the UAE are not addressed by the international community through regulation and monitoring, they will set a dangerous precedent for the rest of the 21st century of launching cyber war operations to achieve power and political ends.

The GCC Crisis and Fears of Democratization

Although today a form of a “Digital Geneva Convention” is more vital than ever, such regulations should also ensure freedom of expression and the press in the digital sphere. While media tools can be used as a means of warfare to justify conflicts and suppress freedom of expression and the press, free media platforms are essential constituents of democratic governance.

Participatory democracy is built on the premise of an informed public, which is made possible only through the concept of the public sphere. The public sphere is a network of communicating points of view on issues of public concern, where information is subject to informed discussion and independent political debate. In today’s digital era, this type of independent public debate is often enabled by media platforms.

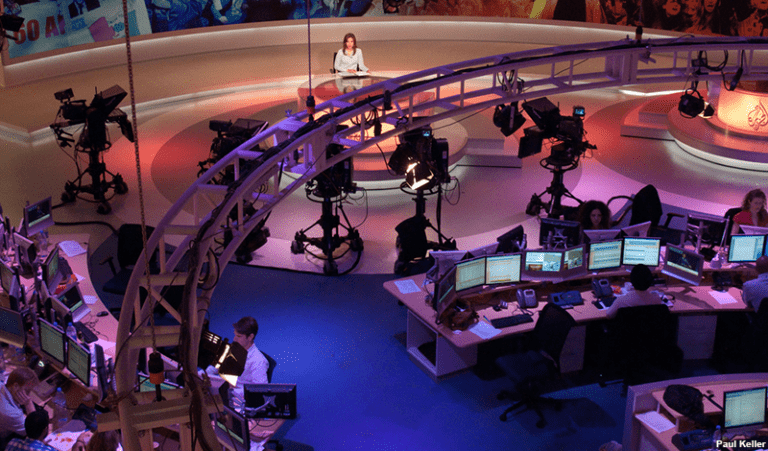

In the Arab world, this was not even imaginable before the 1990s, when Arab media outlets across the board were the official government mouthpieces in their respective countries. The onset of satellite technologies in the 1990s revolutionized the Arab media industry, allowing for private and independent commercial media organizations and providing platforms for different political parties and opposition groups to express their views.

Satellite technology presented the first pluralist forums of free debate and discussion, and essentially led to an information revolution in the Arab world. By transcending government control, holding government institutions accountable, and enabling citizens to engage with the political process, the media became a vital catalyst for democratization during the first decade of the 21st century. However, when the blockading countries in the GCC crisis presented the 13-point ultimatum to Qatar, the Saudi-led quartet demanded the shutdown of several media organizations, including Al Jazeera and others. This demand threatens not only to shut down media organizations but also to block any possibility for a functioning public sphere in the Arab world, thereby suppressing forums of independent discussion of issues of public concern.

In addition to the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government, the media is considered the “fourth estate” whose role is to be the watchdog of government action. In this regard, the media holds a crucial responsibility to inform citizens, scrutinize the institutions of government, and prepare and enable the public to actively participate in democratic politics. The Arab public today can choose among hundreds of TV channels expressing different perspectives and thousands of online platforms to obtain information (and entertainment). The freedoms of the press and expression are vital for the promotion of a democratic culture in the Arab world and must be protected.

The demands to shut down media organizations not only violate the principles of democracy and free press, but also human rights and international law. For example, UN General Assembly resolution A/Res/36/103 grants people the right to free access to information and it endows states with the right to establish media organizations and systems of information. Additionally, the UN Human Rights Council considers closures of media outlets as attacks against journalists and calls on states to establish safe environments for them. As such, demands to shut down media institutions are in violation of UN resolutions and international law.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with the approaches or agendas of certain media organizations, the response should not be to suppress freedom of the press and violate the people’s right to information. In cases where there might be valid and legitimate concerns about possible negative effects of media content and reporting, certain measures can be taken such as fact-checking, employing methods to verify sources, facilitating and encouraging evidence-based reporting, and introducing media literacy programs that provide citizens the tools and skills necessary to assess and verify sources of information. This is not only a concern for traditional mainstream media outlets, but more so online with the increasing presence and voices of alternative and independent sources, which can be a positive development but can also have negative consequences.

Powerful autocratic states will try to counter and suppress alternative sources of information and viewpoints to ensure their sole narrative and political survival. However, the freedom of the press and the right to information must be promoted and protected not only as fundamental human rights but also as necessary prerequisites for democracy and as tools of democratization in the Arab world. It is advisable that any proposals for regulating the cyber sphere and instituting international digital conventions not only focus on the negative consequences of cyber operations, but they must also ensure the protection and facilitation of pro-democracy initiatives.