Lebanon and Israel have frequently been at odds during their nearly two years of negotiations over the two countries’ Mediterranean maritime border, with difficulties arising from both geopolitical and economic considerations. The negotiations also began as Lebanon was just beginning to face serious political, economic, social, and security challenges. In October 2019, a government decision to impose a fee on WhatsApp led to a widespread revolt that forced then Prime Minister Saad Hariri to resign from office. This was followed by the beginnings of a drastic economic collapse, which necessitated bank closures and thoroughly discredited the country’s political class, depriving it of legitimacy. On August 4, 2020, a massive explosion at the Port of Beirut further deepened the crisis, and also increased already high levels of public distrust of Lebanon’s political establishment. The blast even resulted in US sanctions against former Minister of Finance Ali Hassan Khalil and former Minister of Transportation and Public Works Yusuf Finyanus because of their connections to the explosion and their having engaged in corruption.

In October 2020, a scant two months after what was one of the world’s largest non-nuclear explosions at the Port of Beirut, and with the country quickly sliding into total economic collapse, Lebanese Speaker of Parliament and leader of the Amal political movement Nabih Berri announced that Lebanon would relaunch indirect negotiations with Israel to solve a decades-long maritime border dispute in the Mediterranean Sea. He declared that Lebanon had asked the United States to mediate talks between the two countries and that going forward, Lebanese President Michel Aoun would oversee the dossier. Indirect negotiations thus began on October 14 in the village of Naqoura on the border with Israel, in the presence of United Nations Special Coordinator for Lebanon Jan Kubiš and American diplomat John Desrocher.

In the nearly two years since, negotiations have failed to solve the ongoing dispute. This is due to several factors, including the discovery of additional hydrocarbon resources in the area, disagreements over how to delineate the borders in the first place, and external political considerations.

In the nearly two years since, negotiations have failed to solve the ongoing dispute. This is due to several factors, including the discovery of additional hydrocarbon resources in the area, disagreements over how to delineate the borders in the first place, and external political considerations. Perhaps most significant is the fact that Lebanese politicians continue to see the issue as a means to regain much-needed public support. This tactic has worked so far, but with negotiations stalled and with Hezbollah now jumping into the fray, it remains unclear how the situation will develop going forward.

Timing and Considerations

The Lebanese-Israeli negotiations faced considerable problems from the very beginning. To start, their timing was highly questionable, as they were launched at a moment when Lebanon’s political class was almost totally isolated from any public support, and with protesters in the streets forcibly demanding the dismantling of the country’s corrupt political system. The willingness of the Trump Administration to play a mediating role was also problematic. The United States, whose sanctions on Khalil and Finyanus had signaled its antipathy toward Lebanon’s political elite, agreed to take part in the negotiations despite undoubtedly knowing that these same politicians were merely attempting to use the process to try and win back public support—an act of survival more than anything else.

For the United States, meanwhile, the negotiations were seen as an additional way for then President Donald Trump to appeal to pro-Israel voters, thus portraying himself as a friend of Israel and capable of bringing its enemies to the negotiating table in order to deliver stability and prosperity. The US administration would certainly have viewed this as another success after the signing of the Abraham Accords.

On the political front, sitting down with Lebanon to discuss a deal that could bring stability between the two countries holds more significance for Israel than do the peace treaties it has signed with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan.

As for Israel, it joined the negotiations out of a desire for political security and concern for its economic interests. On the political front, sitting down with Lebanon to discuss a deal that could bring stability between the two countries holds more significance for Israel than do the peace treaties it has signed with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan. Such a deal would send a message that Israel is on its way to becoming accepted and formally recognized by the Arab countries immediately surrounding it, a win that Israel touts as capable of bringing stability and accompanying investment opportunities. In terms of security, maritime negotiations could lead to a deal that would discourage Hezbollah from attacking Israeli natural gas platforms near Lebanese borders. Israel would benefit economically as well, since a deal with Lebanon would encourage more companies to invest in Israeli gas exploration and extraction, which would in turn increase Israel’s gas reserves, which it will need as it transitions to an economy based on renewable energy.

Deadlock from Day One

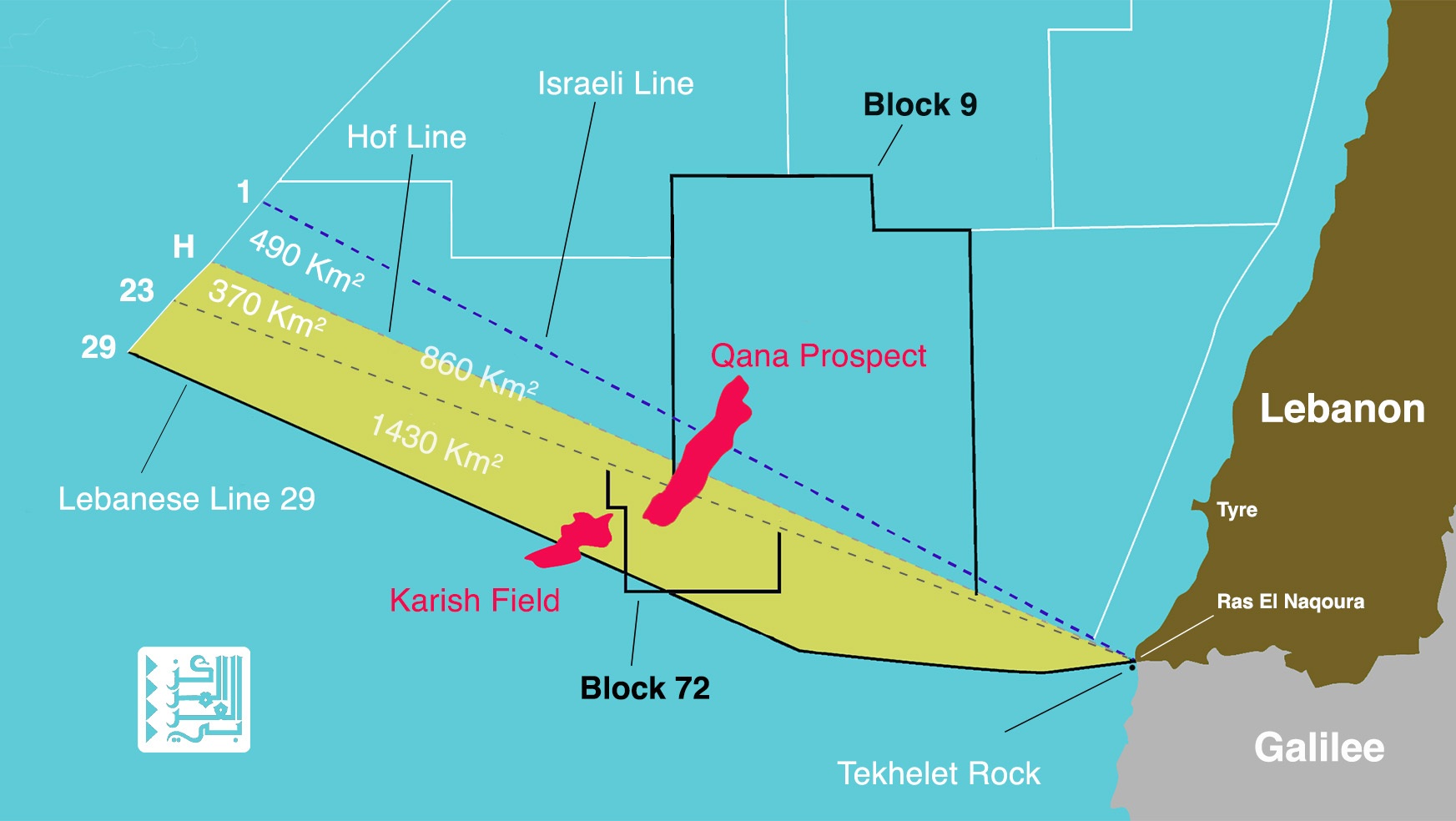

The maritime dispute between Lebanon and Israel began during a stretch of several months from 2010-2011 when both countries submitted to the United Nations different maps and coordinates depicting their respective exclusive economic zones (EEZ). The overlap between the two countries’ self-declared EEZs created 860 square kilometers of disputed area located between Israel’s line 1 and Lebanon’s line 23.

Adapted from maps released by the Lebanese Armed Forces.

All parties went to Naqoura in 2020 after initially agreeing on a six-point framework that was supposed to be the basis for the start of negotiations. But this was more a procedural framework than anything; it did not mention a timeline for the negotiations, or even delineate or describe the disputed area. It did mention, however, that Lebanon and Israel had nominated the US as mediator, that the negotiations would take place in the presence of UN Special Coordinator Kubiš, and that any agreement would be sent to the UN as an official record.

From day one, there was clear disagreement between the negotiating teams. Israel and the US were under the impression that the negotiations would only cover the disputed area of 860 km2, but the Lebanese team came to the table with different maps, wanting to discuss an area covering 2,290 km2 in total. This marked the first public appearance of a new line, line 29, which increased Lebanon’s territorial claims. The Lebanese negotiating team insisted that line 23 had been drawn at random and lacked any methodological foundation. The team therefore proceeded to defend the use of line 29, relying on a method acknowledged by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea—to which Lebanon is a signatory—which uses a three-stage approach. This approach consists of: First, drawing an equidistant line; second, looking for special circumstances; and finally, checking for any disproportionate effects in the final drawing. Based on this methodology, Lebanon argued that it had the right to claim an additional 1,430 km2 beyond the original area of 860 km2 as delineated by line 23.

From day one, there was clear disagreement between the negotiating teams. Israel and the US were under the impression that the negotiations would only cover the disputed area of 860 km2, but the Lebanese team came to the table with different maps, wanting to discuss an area covering 2,290 km2 in total.

From October 2020 until May 2021, the negotiating teams met five times at Naqoura, though the discussions were of a purely technical nature. The Lebanese team argued that the starting point for the border should be Ras al-Naqoura (the outer shoals of Naqoura) and that Tekhelet Island close to the shores of Israel should not be taken into consideration because of its disproportionate effect. Israel rejected both claims, considering Tekhelet part of the baseline. The Lebanese technical team also argued that Israel’s line 1 was incorrect because it was not based on what Lebanon considered the correct starting point of Ras al-Naqoura. The Israeli team, meanwhile, categorically refused to discuss any deal that covered an area beyond the 860 km2 that had already been under dispute for a decade. The US sided with Israel, insisting that Lebanon had made no official claim on additional areas, since the maps and coordinates it had sent to the UN in 2011 clearly recognized line 23 as the maritime border between the two countries. The negotiating teams thus reached a deadlock.

Lebanon’s Internal Politics

No issue in Lebanese foreign policy is ever free of the country’s internal political complexities. Soon after the negotiations started in October 2020, public opinion in Lebanon was divided between those supportive of the negotiating team’s position claiming line 29 and those in support of line 23. The matter very quickly became a blame game played by opposing political parties, chief among them the Free Patriotic Movement and the Lebanese Army, both of which supported the use of line 29, and the Amal Movement, which argued for using line 23. Public opinion in favor of the negotiating team’s insistence on line 29 pressured the caretaker government of then Prime Minister Hassan Diab to amend decree 6433 of 2011—which had included the EEZ coordinates that were sent to the UN—to instead claim line 29 as the correct maritime border.

Suddenly, the true center of the negotiations had moved from Naqoura to Beirut, as the real debate became one among various Lebanese political factions, rather than one being held between the Lebanese and Israeli negotiating teams. And the Naqoura meetings stopped altogether in May 2021 after President Aoun refused the United States’ condition that talks cover only the original 860 km2 area under dispute.

Suddenly, the true center of the negotiations had moved from Naqoura to Beirut, as the real debate became one among various Lebanese political factions, rather than one being held between the Lebanese and Israeli negotiating teams.

Amid the turmoil of internal Lebanese discussions on the dispute, a new factor came to light: oil and gas fields. First, the proposed line 29 would split in two the Israeli Karish natural gas field, which was discovered in 2013 and is due to start production in the third quarter of 2022. Lebanese citizens and politicians therefore viewed the insistence on line 29 as an important tool to put pressure on Israel to accept a win-win deal. Israel, however, was likely eager to finalize a deal as quickly as possible, to stave off any delays that could jeopardize extraction by the private company Energean, which is developing the Karish field.

While the Lebanese public was just learning about Karish, another bombshell was tossed into the public sphere: a gas prospect in block 9 in the Lebanese EEZ, part of which could possibly end up under Israeli control if negotiations don’t go Lebanon’s way. That prospect soon had a name, Qana, and quickly became the obsession of all. The mission to “save” Qana was launched by the political establishment and President Aoun, who in April 2021 refused to sign amended decree 6433, claiming it needed a national consensus and a resolution from the council of ministers. And Aoun still has not even once discussed the decree with the government of current Prime Minister Najib Miqati.

The effect of this series of events was that the discussion inside Lebanon shifted from accusations of government corruption and mismanagement to debates about the need to find creative solutions to finalize a maritime deal that would allow Lebanon to exploit its potential offshore gas resources. The negotiations thus achieved for Lebanon’s political elites exactly what they had hoped it would, allowing them to downplay criticism and win back public support.

Shuttle Diplomacy with a New US Mediator

The US attempted to restart negotiations in October 2021 by appointing US businessman and diplomat Amos Hochstein to mediate the talks. Hochstein immediately recognized Lebanon’s need to quickly develop its hydrocarbon sector in order to catch up with its neighbors, who are more advanced in this regard. Building on his knowledge of the border dispute and of the Lebanese politicians involved in it, which he had developed while serving in the Obama Administration, Hochstein adopted a shuttle diplomacy approach in order to bridge the gap between Lebanon and Israel’s positions. When he visited Beirut in October 2021, he listened to various demands and views on this “battle of lines” among Lebanon’s politicians and parties. But when he returned to Beirut in February 2022 Hochstein simply reiterated the US position that the only disputed zone is the one measuring 860 km2, and that because this is a process of negotiation, no single side will obtain control over the area in its entirety.

Building on his knowledge of the border dispute and of the Lebanese politicians involved in it, which he had developed while serving in the Obama Administration, Hochstein adopted a shuttle diplomacy approach in order to bridge the gap between Lebanon and Israel’s positions.

Hochstein left Beirut on February 10, and two days later Aoun stated in an interview with pro-Hezbollah newspaper Al-Akhbar that he recognized line 23 as the official maritime border between Lebanon and Israel and that line 29 was without foundation. This was the position the US mediator was awaiting in order to send his proposal to the Lebanese government, which he did a few weeks later. The Lebanese president, prime minister, and speaker of parliament reportedly met to discuss the proposal, but sent no official reply. It was not until four months later, when an Energean-owned floating production storage and offloading system arrived at the Karish field that the Lebanese government called Hochstein to Beirut and submitted a counterproposal.

The government told Hochstein that it wanted the entire Qana field for itself. This meant that Lebanon was demanding the entire 860 km2 area, and parts of block 72 from the Israeli side. This was Lebanon’s attempt to avoid a resource-sharing agreement with Israel, which it does not officially recognize. The country essentially proposed that it would give up any claim over the Karish field in return for Israel’s giving away any rights to Qana. Hochstein shared the Lebanese proposal with the Israelis, who urged him to continue to bridge the gap, meaning that the proposal was not accepted or that the Israelis needed more details, especially on the Qana prospect that Lebanon is so keen on preserving for itself.

The initial US proposal had given Lebanon the opportunity to begin exploiting the prospect in block 9, while guaranteeing that Israel would not object to Lebanon’s development in this regard, as whatever company develops block 9 would have to make a financial arrangement with the holder of Israeli block 72. However, the Lebanese side is now trying to pressure the US and Israel to give up block 72 entirely. This helps make sense of the latest Hezbollah drone flights over the Karish field, which can be understood as an attempt to squeeze a better deal from the US. Hezbollah-affiliated politicians will not be able to sign off on a deal that includes any kind of resource sharing or joint development agreement with Israel, and Hezbollah is therefore resorting to force in order to save the Qana field for Lebanon.

Another Missed Opportunity?

Before these most recent drone flights, which were condemned by both Hochstein and US Ambassador to Lebanon Dorothy Shea, Hochstein had been hopeful that he could finalize a deal within two months. But as it is, much remains up in the air. Hezbollah’s escalation may renew the push for a deal, or it may very well be a deal breaker. And it is not clear whether the United States will end the negotiations altogether if the flights continue. Meanwhile, President Aoun certainly wants an achievement to tout before the end of his mandate in October, but his political rivals may not want him to achieve such a gain. It is also uncertain whether preparations for Israel’s November elections will raise the government’s interest in reaching a deal before polls open. What will all this mean for Lebanon’s dreams of becoming an oil and gas producer? The coming days and months will undoubtedly hold the answer.