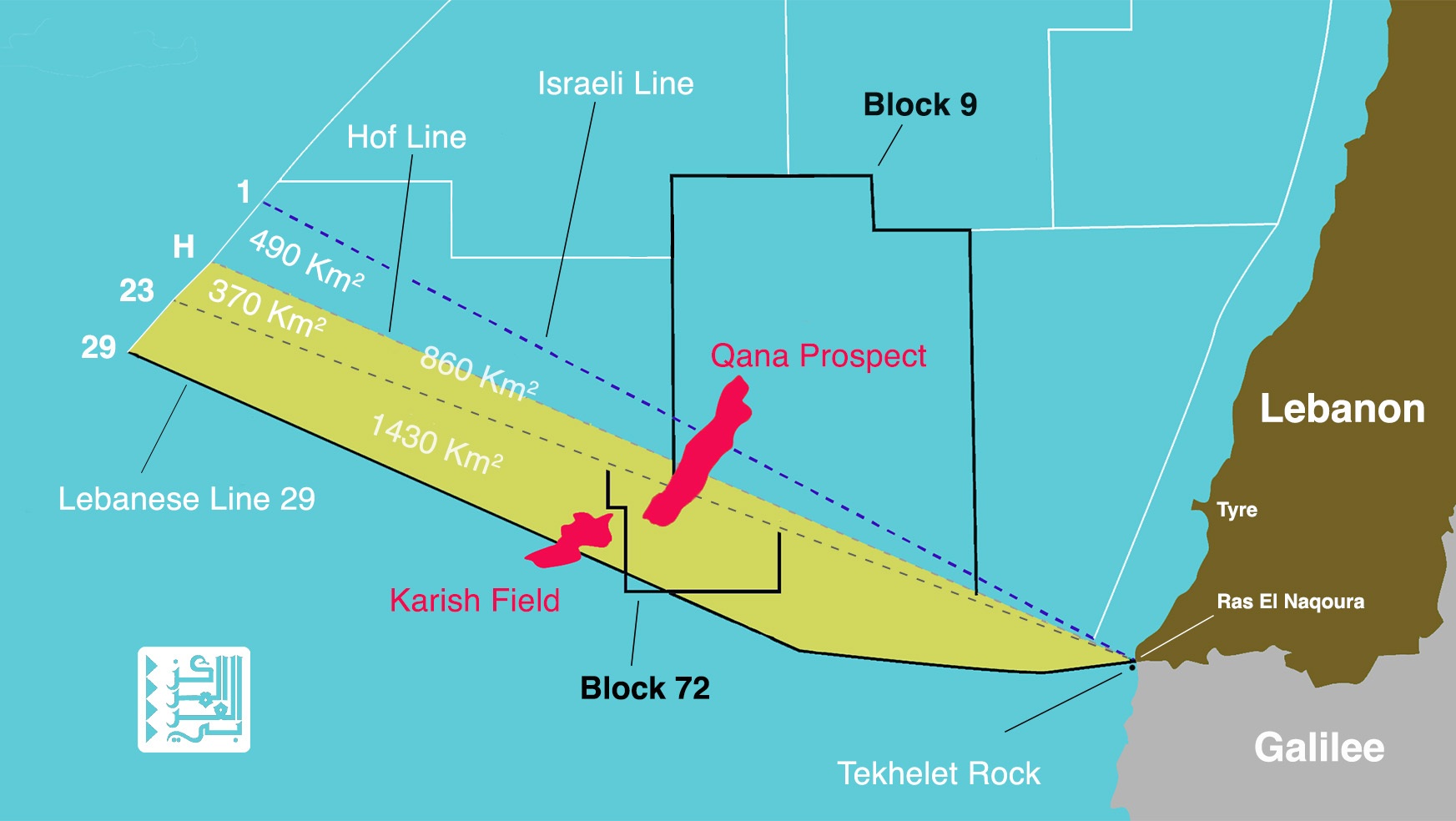

After ten years of on-again, off-again negotiations, Lebanon and Israel have finally reached what leaders in both countries consider an acceptable deal to demarcate maritime borders between the two countries and to manage the exploration for and the extraction of oil and gas deposits in the Eastern Mediterranean. On October 27, the two countries submitted their official letters approving the deal to US Envoy for Energy Amos Hochstein at UN offices in Naqoura, a coastal town on the Mediterranean coast. Prior to the agreement, Lebanon rescinded its demand to use Line 29 (see map) as its southernmost maritime border, and instead accepted Line 23, while also insisting that it have full control over the Qana gas field, which crosses Line 23. Israel, meanwhile, initially demanded that it share revenues from the Qana field with Lebanon, a stance that complicated the possibility of an accord due to a longstanding official state of belligerency between the two countries.

But it has become clear in the few weeks since the initial announcement of an agreement on October 12 that only Israel can be said to have obtained a satisfactory end result in the US-brokered talks, which were mediated by Hochstein. Lebanon appears to have settled for the mere hope of finding and extracting fossil fuel resources for which its population is in desperate need. To be sure, while Israel’s already extant infrastructure will allow it to explore, extract, and distribute its undersea gas bounty, Lebanon will have to wait for quite some time before it can exploit what are so far unproven gas deposits on its side of the new border. It also appears that Israel has managed to breach the previously impenetrable wall of Lebanon’s refusal to normalize relations, despite adamant yet dubious denials from Lebanon’s leadership that the current agreement represents a form of normalization.

Much Ado about a Flawed Agreement

On October 12, mediator Hochstein sent the details of the maritime demarcation agreement to the Lebanese and Israeli governments for approval, in preparation for a final signing two weeks later. In the interim, Lebanon approved the proposed text of the agreement, as did Israel’s full cabinet and its supreme court. US President Joe Biden, naturally eager to chalk up the agreement as a US foreign policy achievement, congratulated Lebanese President Michel Aoun and Israeli caretaker Prime Minister Yair Lapid on ending their maritime boundary dispute. However, Biden went a bit too far in claiming that the two countries had agreed to “establish a permanent maritime boundary,” since the finalization of the boundary still appears to be very much dependent on future negotiations.

A sketch of the areas of dispute in the eastern Mediterranean. Adapted from maps released by the Lebanese Armed Forces.

The new agreement states that a maritime demarcation line has been assigned between the two countries along specific sets of coordinates. But the text of the agreement is unclear as to what that line really is, since it stipulates that demarcating the line depends on delimiting an acceptable land boundary, one that has not yet been negotiated. In circular fashion, the text of Section 1B states, “In order not to prejudice the status of the land boundary, the maritime boundary landward of the easternmost point of the MBL [maritime boundary line] is expected to be delimited in the context of, or in a timely manner after, the Parties’ demarcation of the land boundary.” The text also tries to make permanent a line of water buoys that Israel previously strung in disputed waters after its withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000 and to use that line as a maritime border. Lebanese President Michel Aoun rejected this proposal as he announced Lebanon’s acceptance of the recent agreement. In other words, while signing the agreement may be accomplished, the actual dispute over the maritime border remains unresolved.

Section 2 of the agreement deals with the Qana gas field, which lies mainly in areas demarcated as Lebanese (Block 9), and partially in those designated as Israeli (Block 72). To avoid the complication of Lebanon’s non-recognition of Israel and its refusal to engage in direct negotiations and dealings with the Zionist state, the agreement stipulates that the operator of Lebanon’s gas fields, French multinational company Total Energies, would agree with Israel on a financial arrangement, under which the former would provide a portion of its profits to the latter. In this way, Lebanon can claim to be totally free of any obligation to Israel—a country it does not officially recognize—while Israel can still receive payment for energy resources extracted from its waters. The agreement also specifies that any operator in Lebanese waters cannot be a sanctioned corporation, cannot be an Israeli or Lebanese entity, and cannot reject American facilitation.

Of special concern in Section 2 of the agreement are statements that allow Israel to scuttle the deal or to prevent Lebanon from exploiting its side of this shared gas field. For example, Section 2D expects that the operator of the field may need to conduct “navigational maneuvers” on the Israeli side of the (so far) undetermined maritime boundary over Qana, but stipulates that Israel must receive “prior notification.” It is therefore up to Israel to allow an operator to do what is necessary for its exploration activities. The section also uses vague wording and phrases that could be interpreted in various ways according to the whims of Israel, the stronger party. Some examples include: “Israel will not object to reasonable and necessary activities” (Section 2D); “Israel shall work with the Block 9 Operator in good faith” (Section 2E); “Israel will not unreasonably withhold such consent” (Section 2E); “Israel will not…take any action that unduly delays reasonable activities” (Section 2F). In other words, it is up to Israel to define what is reasonable, necessary, timely, in good faith, or unduly. Importantly, there are no prohibitions against Israel’s use of these stipulations and conditions to delay or to entirely stop Lebanon’s attempts to explore for and exploit potential gas riches.

What is especially interesting in this regard is the agreement’s emphasis on the remuneration of Israel for any profits made from its side of the Qana field. Lebanon’s poor energy infrastructure, as well as the mere fact that the extent of gas deposits in Qana remains unknown, makes the issue of compensating Israel a moot point for years to come.

What is especially interesting in this regard is the agreement’s emphasis on the remuneration of Israel for any profits made from its side of the Qana field. Lebanon’s poor energy infrastructure, (specifically seaside storage facilities and maritime exploration, extraction, and transport), as well as the mere fact that the extent of gas deposits in Qana remains unknown, makes the issue of compensating Israel a moot point for years to come. The stipulation that Israel be paid for what it owns of the field’s potential riches gives the Zionist state the ability to act as an overseer of Lebanon’s activities in the area. And as an overseer, it could determine how Total Energies conducts its exploration, what and how much gas extraction to report, and whether Lebanon can truly exercise its sovereign right as an independent state. Indeed, there is no clear sign that Israel will truly act “in good faith,” since just two weeks ago, on October 16, its navy violated Lebanon’s territorial waters, just as Hochstein was receiving accolades for what many have lauded as a seminal accomplishment on demarcating the border.

A Long Wait for Lebanon to Benefit

For Lebanon, the agreement is not likely to produce much benefit in the foreseeable future, for at least two reasons. First, no exploration of the Qana field has been conducted, which means that Lebanon will be unable to boast quick returns on the agreement. As soon as the agreement was announced, Lebanon’s caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati asked Total Energies to “immediately” start operational plans for work. Indeed, urgency is the name of the game here, especially considering Lebanon’s deep economic problems. But no one can be sure that a bounty of hydrocarbon riches will be found in any given spot under the sea. Even if such a bounty does prove to be present, extracting, transporting, and storing it will be a challenge for years to come. In 2020, Lebanon conducted a search for gas deposits in Block 4, situated in Lebanese waters far north of the new border with Israel, but was disappointed to find “no commercially viable amount of gas to develop.” To be sure, experts have warned that politicians should not raise people’s hopes about immediate riches because as of yet, no one possesses complete information about the matter.

Lebanon suffers from institutional chaos and elite disunity, which make it practically incapable of making the necessary executive decisions that would help launch its oil and gas industry if commercially viable deposits were found.

Second, on the political front, Lebanon suffers from institutional chaos and elite disunity, which make it practically incapable of making the necessary executive decisions that would help launch its oil and gas industry if commercially viable deposits were found. The country has in fact just entered a presidential vacuum since Lebanon’s parliament has now failed on many occasions to elect a successor to President Michel Aoun, whose term expires October 31. Sessions for electing a president were held to no avail, since Parliament repeatedly failed to secure the required quorum—two-thirds of parliament’s 128 members—and individual candidates time and again proved incapable of receiving enough votes to be declared a winner. Moreover, the current government exercises its authority in a caretaker fashion, which means that its decisions have to be unanimous in order to be legal, essentially making each minister a sole authority on their own. Prime Minister Mikati, meanwhile, seems to be operating on the premise that no president will be elected by October 31, and that no new government will be formed before that time either. Considering Lebanon’s current political stalemate, a presidential vacuum is likely to paralyze any effective action regarding the Hochstein agreement.

De Facto Normalization

Indeed, it is hard to see the United States’ “success” in mediating this agreement as anything other than a boon for its ongoing push to normalize Arab relations with Israel. It is also hard to believe that Lebanon’s signing a deal with Israel (albeit indirectly through Hochstein and at a United Nations liaison office) will be understood as anything less than an actual recognition of the Zionist state. To be sure, Israeli caretaker Prime Minister Yair Lapid declared that this is exactly what actually transpired. Regardless of the fact that former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu—who is Lapid’s main challenger in Israel’s November 1 parliamentary elections—commented that the agreement was a “historic capitulation,” Israel’s leaders appear to believe that they have managed to break through Lebanon’s objections to normalizing relations. And Frederic Hof, a US foreign policy veteran who was a mediator in negotiations over the border when they first began in 2012, wrote that he sees a “potential opportunity” for normalization between the two countries.

It is hard to see the United States’ “success” in mediating this agreement as anything other than a boon for its ongoing push to normalize Arab relations with Israel. It is also hard to believe that Lebanon’s signing a deal with Israel will be understood as anything less than an actual recognition of the Zionist state.

Even if direct normalization is not in the offing at the present time, and even if Lebanon is not on its way to signing onto the so-called Abraham Accords, Israel has finally achieved a high degree of security with this deal. Hochstein was careful to note when commenting on the deal that it gives Israel both “security and stability.” Hezbollah, which has long threatened Israel and cautioned it about exploring and exploiting its Karish gas field before Lebanon could do the same in Qana, recently announced that it has ended its “exceptional” mobilization, which in essence means ending its state of war with Israel. This development is actually one of the most striking in the present context. Hezbollah was the main force objecting to any deal with Israel, and is now acting as the official political shepherd of an arrangement that provides Israel with the security it needs to develop its gas fields in the Mediterranean.

After holding out on reaching a maritime demarcation agreement with Israel since 2011, Lebanon finally accepted what can only be considered a deal that facilitates Israel’s free and full exploitation of its gas deposits in the Eastern Mediterranean. Given Israel’s advanced energy industry and infrastructure, it will soon be exporting its riches to Europe, where energy supplies are at a high premium as a consequence of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In exchange, Lebanon received only uncertain assurances that it will be allowed to explore its own so far unproven energy reserves. But Lebanon’s political stalemate and poor infrastructure will prevent it from entering the club of fossil fuel-producing nations and from addressing its deep financial problems if and when that goal is achieved. Moreover, in signing this agreement, Lebanon may have given Israel the security and recognition that it has long sought with little tangible benefits in return.

Featured image credit: Flickr/US BSSE