As the summer comes to a close, indirect negotiations to demarcate the maritime border between Lebanon and Israel continue apace. Although US mediator Amos Hochstein’s shuttle diplomacy has not yet produced an agreement that is acceptable to both sides, there are faint indications that a deal is in the works. Hochstein will reportedly return to the region on September 7, supported by a White House that is keen on helping the two countries to arrive at a deal. But Lebanese leaders have been worried that the demarcation process may be delayed by complications arising from Israel’s upcoming November 1 legislative elections, and by Lebanon’s presidential election, slated for the end of October.

Many hurdles must be surmounted in order to reach a quick and just compromise to this problem. Setting aside the distinct possibility that Israel may simply not be ready to conclude a deal, the two main impediments are the swirl of competing interests present in Lebanon’s domestic political sphere and Hezbollah’s involvement—since the party has appointed itself an arbiter of what it deems to be in the country’s best interest. Hochstein may indeed return to Beirut with an acceptable solution. But doubts remain about whether institutional inertia and elite differences can be overcome so that Lebanon can find some way out of its deep economic troubles. But considering the power disparity between the two countries, as long as Lebanon remains in the throes of political and economic chaos and unable to nudge things along, Israel could simply continue to hold out on reaching a deal—at least until its elections are over.

Where Things Stand Today

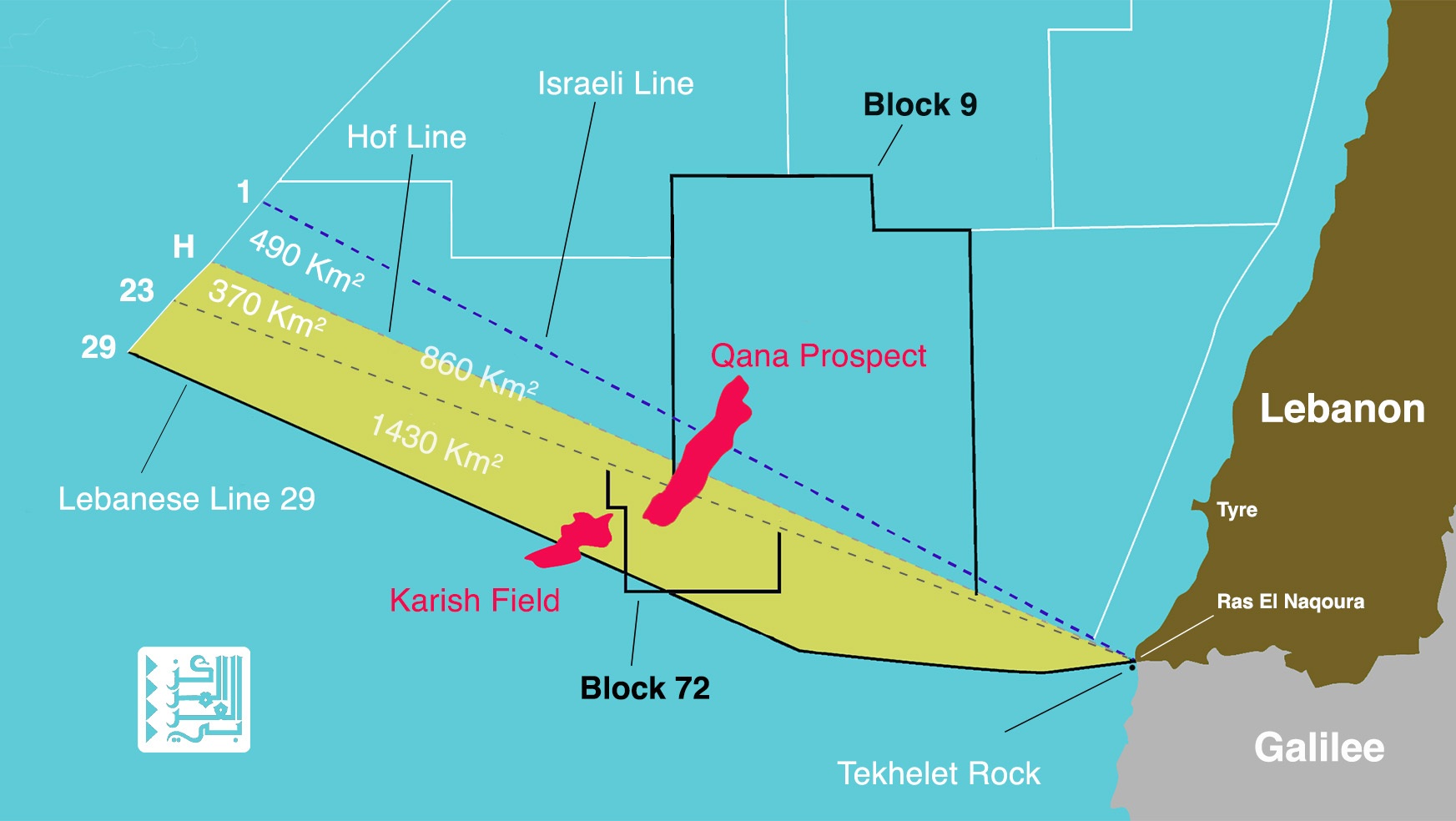

Lebanese-Israeli maritime border negotiations have been taking place on and off since 2011, and have been focused on separating the two countries’ exclusive economic zones in the eastern Mediterranean. In June 2022, Israel dispatched an exploration rig to the Karish gas field, prompting Hezbollah to fly unarmed drones over the platform to send a message that Israel should not attempt to exploit the field before Lebanon’s approval. The drones were shot down by Israeli aircraft, but Hezbollah’s move threatened to spark an escalation that was, and still is, undesirable. Following these developments, Lebanon proposed a more realistic potential solution to the demarcation issue. Despite having stubbornly and fruitlessly insisted in previous negotiations on using Line 29 for demarcation (see map), it accepted Line 23 as the maritime border, demanded ownership and control over the Qana field that crosses Line 23 into an area claimed by Israel, and acknowledged Israel’s sovereignty over the Karish field.

Adapted from maps released by the Lebanese Armed Forces.

Hochstein traveled to Israel to convey the new Lebanese position, but then ignored Beirut for quite some time, which worried Lebanese officials, especially outgoing President Michel Aoun, who seems desperate to be the one to get the credit for concluding a deal. But positive signals still abounded, showing that Hochstein was making progress. Even Lebanese Speaker of Parliament and Hezbollah ally Nabih Berri indicated that his talks with Hochstein when the latter was last in Beirut were “positive.” And Hochstein himself was also apparently happy to see unity on the issue among Lebanese politicians. In a phone conversation on August 24 with Lebanese Deputy Speaker of Parliament Elias Bou Saab, an Aoun supporter, Hochstein communicated that Israeli leaders were taking the discussions very seriously. He added that while an agreement may not be imminent, the timeline is not open-ended.

Hochstein himself was apparently happy to see unity on the issue among Lebanese politicians.

But Hochstein’s long absence from Beirut and the delayed Israeli response to Lebanon’s last proposal prompted Hezbollah to try to shake things up. The party’s Secretary General, Hassan Nasrallah, issued a warning on August 9 that “any arm” trying to steal Lebanon’s wealth “will be cut off.” Whether the warning was issued for public and political consumption is up for debate, but Nasrallah again renewed the threat on August 19, only to be answered this time by Israeli Defense Minister Benny Gantz, who threatened all-out war if Hezbollah attacks any of Israel’s gas assets.

Regardless, the Jerusalem Post reported on August 30 that Israel and Lebanon’s positions are very similar, and that Lebanon may be given the full control over the Qana field that it demands, as long as it pays compensation to Israel. However, Hochstein also recently visited Paris to discuss the issue with French oil company Total, which holds exploration rights in Lebanese waters. In addition, Israel postponed the start of its gas exploration efforts until later in September, apparently allowing the US mediator time to find a workable formula. Indeed, Hochstein’s latest moves send a signal that something is truly afoot.

Turkey, perhaps looking to become a player in Lebanon’s energy sector, is reported to have submitted a proposal to the Lebanese government to explore for gas in Block 9, which abuts the disputed 860 km2 area lying between Line 23 and Line 1. Lebanon’s caretaker Energy Minister Walid Fayad, however, disputed the report, saying that no such proposal has been received. Whatever the case may be, Lebanon and Israel—as well as many other states with a stake in eastern Mediterranean energy sources—are eager to demarcate the maritime border so that work can begin on exploring for and extracting gas from the area in dispute. With global energy demand remaining high and short supplies continuing to burden the international economy with high prices, the United States, Europe, Lebanon, and others would be happy if a resolution to the demarcation issue were to arrive soon.

The Uncertainty of Lebanon’s Presidential Election

Amid difficult political, economic, and security conditions, Lebanon is practically stumbling toward its scheduled constitutional transfer of power on October 31. If President Aoun is deprived of the glory of being the one to sign a demarcation agreement with Israel, then a new president must do so once elected and sworn in. But considering current conditions in Lebanon, a presidential vacuum appears altogether possible, which may further delay the finalization of an agreement on the border dispute. According to Article 73 of the Lebanese constitution, the speaker of parliament must convene a parliamentary session to elect a president at least one month and at most two months before the expiration of the incumbent’s term. But Speaker Berri has not done so thus far. In July, Berri said that he would not call a session for the election of a new president until parliament passes a reform law that is a prerequisite for receiving a $3 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund. His reasoning refers to Article 75 of the constitution, which stipulates that once a presidential election session is opened, parliament cannot debate laws or legislate important economic and social issues. And another law awaiting debate and passage is one concerning reforming the banking system, which was a major factor in Lebanon’s current financial trouble.

Considering current conditions in Lebanon, a presidential vacuum appears altogether possible, which may further delay the finalization of an agreement on the border dispute.

Not even the country’s expected presidential candidates can be sure of the degree of support they will have in parliament, divided as it is along two general perspectives: one calling for strengthening the state’s institutions and imposing its writ over the entire country, and another supportive of Hezbollah’s special role within the Lebanese polity. An obvious representative of the first group, if he were to run, is Samir Geagea, leader of the Lebanese Forces Party and a longstanding opponent of Hezbollah. Two other potential candidates who represent the pro-Hezbollah group are Suleiman Frangieh, leader of the Marada Movement, and Gebran Bassil, who is a member of parliament, leader of the Free Patriotic Movement, and President Aoun’s son-in-law. A possible candidate representing a middle-of-the-road perspective, meanwhile, is Commander of the Lebanese Army General Joseph Aoun (no relation to Michel Aoun), who has both domestic and foreign support, and who would give the position the respect and authority it deserves.

Further compounding these factors is a continued delay in forming a new government to replace the current caretaker cabinet. Caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati has been chosen by parliament to form the country’s new government, but he and President Aoun have so far failed to agree on the new cabinet. Perhaps that is why Mikati has announced that his government could assume presidential powers if no president is elected. While this possible development raises serious questions due to the consociational nature of Lebanese politics (the president must be a Maronite Christian and the prime minister a Sunni Muslim), it could work as an alternative method by which to agree to a maritime border compromise with Israel. And it is important to note that Aoun himself gained the presidency following a presidential vacuum that lasted from May 2014 to October 2016.

Hezbollah Seeking Legitimacy

It would not be an exaggeration to state that a maritime border demarcation agreement between Lebanon and Israel would be impossible to achieve without Hezbollah’s approval. The party has been trying to shake off the perception that it is a protector of the corrupt political system—especially after its cadres attacked protestors in Beirut in 2019—and has therefore sought ways to reassert its legitimacy among the Lebanese people in the wake of the country’s widespread economic and social collapse. Hezbollah’s loss of a parliamentary majority in last May’s elections was a clear signal that its popular support among non-Shia constituencies has eroded. The party has now decided to try to compensate by championing a nationalist cause that it believes will lead others to rally around it once again.

Hezbollah has been seeking ways to reassert its legitimacy among the Lebanese people in the wake of the country’s widespread economic and social collapse.

Last June, as Israel sent its Energean exploration rig to the Karish field, Hezbollah’s second in command, Naim Qassem, said that the party would defer to the Lebanese government on how to respond, but urged it to act quickly and decisively. However, as noted above, only a few weeks later Hezbollah changed its position and sent a clear warning to Israel in July via unarmed drones that flew over the rig. This act, along with Nasrallah’s subsequent warnings in August, make clear that Hezbollah is using the maritime demarcation issue to bolster its legitimacy among the Lebanese population. The party is therefore unlikely to accept any solution that does not align with its priorities.

Whatever form the deal between Lebanon and Israel ultimately takes, Hezbollah is sure to prevent it from opening the door to normalization between the two countries. In fact, the Lebanese government has been at pains to declare that it will not. For example, Lebanon’s demand to control the Qana field—which stretches into an area claimed by Israel—has come with an insistence on decoupling from Israel for gas produced there. This stipulation is intended to prevent any possible revenue sharing agreement, which would be a form of recognition of Israel. For Hezbollah, the stakes are especially high, given that the party’s legitimacy is built around its ironclad commitment to fighting, rejecting, and delegitimizing Israel.

Will There Be an Agreement?

It is almost certain that Amos Hochstein’s mission to demarcate the Lebanese-Israeli maritime border will end in an agreement of some sort. The US envoy would not be shuttling back and forth between the two countries if it looked like his efforts would come to naught. But it is doubtful that an agreement is imminent, certainly not one that satisfies President Aoun’s hopes of being the one to sign a deal before the end of his term on October 31. Not only do Lebanon’s institutional troubles and Hezbollah’s quest for legitimacy threaten to stall any progress, but Israeli politicians may also be less than accommodating during what promises to be a heated parliamentary election. Until a deal is reached, Lebanon will have to wait to join the club of energy-exporting nations, a wait that will only prolong its current energy crisis and financial woes.