After an impasse of nearly four years, on March 8 the Lebanese government announced a sectarian quota deal to fill the security establishment’s leadership positions. Amid tensions surrounding Hezbollah’s regional activities, these appointments come at a critical moment for the country’s stability and for the future of US military aid to Lebanon.

What kept Lebanon immune from the spillover of the Syrian war is not necessarily the dissociation policy of its consecutive governments but, most importantly, the crucial decision three years ago to resume coordination among the country’s rival security and intelligence agencies.

That turning point came in 2014 when the Saudi-backed Lebanese intelligence agencies shifted from lack of cooperation with Hezbollah, and not disrupting aid to groups fighting the Syrian regime, to the resumption of counter-terrorism efforts. The August 2014 joint attack by al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) on Arsal, a Lebanese village on the border with Syria, further strengthened that line of cooperation.

The Iranian-backed Hezbollah and the Saudi-backed Future Movement, which had bickered since 2011, found themselves facing a common threat in 2014. The rise of radical elements in the Sunni areas had become a challenge for Hariri’s dwindling influence while Hezbollah had become vulnerable as it protected the Shiite community from an array of suicide attacks without a functional state intelligence system. Hence, scrutiny of the Lebanese security establishment since 2015 helped the country move forward and succeed in thwarting suicide attacks, forcing radical groups to retreat while cutting their funding and logistical support.

Hariri had a choice to make—between coping with Hezbollah’s intervention in Syria while returning to power, or defying it politically from the sidelines. Ultimately, he decided to cope, but not without drawbacks. He had to quell resistance from his own camp, most notably former Minister Ashraf Rifi, who accused him of being complacent with Hezbollah.

The latest appointments reaffirmed the three-year-long security coordination as well as the parameters of last year’s deal that selected General Michel Aoun as president and Saad Hariri as prime minister. Sectarian politics were in full display with a distribution of power among the representatives of the three major confessional communities: President Aoun (Maronite) consolidated his control over the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) by selecting General Joseph Aoun as commander; Prime Minister Hariri (Sunni) consolidated his control over the Internal Security Forces (ISF) by appointing Brigadier General Imad Othman as general director; and Hezbollah/Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri (Shiite) kept Abbas Ibrahim as general director of General Security for another six years (as a civilian after retiring from the military).

Selection Criteria

The “selection criteria” of these appointments have framed the most contentious issue in the last four years. The term is loosely used by the Lebanese oligarchy to mask the decade-long battle of influence to control the security establishment since the Syrian regime’s grip over Lebanon began to fade in 2005. Here are the main selection criteria that informed these latest appointments:

- Each of three confessional representatives selected a list of three options (by order of preference) for the vacancies allocated to them while the other two only had the right to veto.

- While the law says that the government is supposed to appoint only the army commander and the head of ISF, the ruling oligarchy recently preapproved a string of senior-level appointments as part of the larger sectarian quota deal.

- All appointed commanders were new to their positions; there were no extensions of previous appointments, except for Abbas Ibrahim. That was a win for President Aoun, who has been arguing for years against extending the mandate of security commanders.

- No provocative names were put forth—all appointees were officers known for their moderate stances and inclinations to coordinate unless instructed otherwise by their oligarchs.

- Loyalty for respective sectarian leaders was paramount in deciding the appointments.

- The principles of hierarchy and seniority were not respected. Both Joseph Aoun and Imad Othman had to be promoted to take on their new roles, hence officers at ISF and LAF are now compelled to salute younger officers who have less years of service. At least 50 brigadier generals were placed at the disposal of the ISF commander to promote Othman, which means the career of these senior officers is over and all they can do now is wait their turn to retire (AR).

The Defense/Military Establishment

A few Lebanese military commanders shaped the LAF legacy; the first commander, General Fouad Chehab, is perhaps a breed on his own. Yet, there are two influential trends that molded the Lebanese army in the last three decades: the anti-Syrian attitude of General Michel Aoun (who served as commander 1984-1990) and the pro-Syrian attitude of General Emile Lahoud (who served as commander 1990-1998).

The military cohorts, who served under Aoun during the final chapter of the Lebanese civil war, suffered from the ramifications of his military defeat in 1990. When forced into exile by the Syrian invasion, Aoun asked his troops to declare allegiance for his successor Lahoud to save them from further bloodshed. The young officers had the choice either to resign or reluctantly integrate into the new army under Syrian rule.

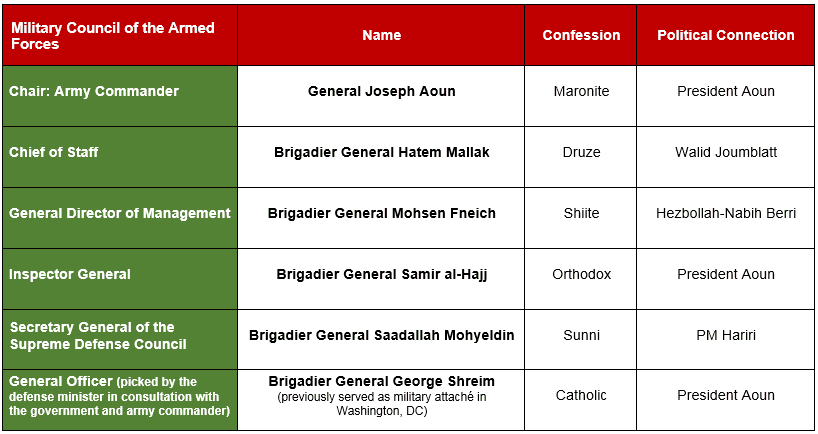

Now, after nearly 27 years, these military officers are again in a position of power: General Joseph Aoun, Brigadier General Samir al-Hajj (Inspector General), and Brigadier General George Shreim (General Officer). All three serve on the six seats of the military council, the highest decision-making body of the armed forces. The council is entrusted with naming commanders across the military and hence can shape the balance of power inside the army for decades to come. According to the National Defense Law, the military council is chaired by the army commander along with five other members (as shown in the table below). The vote is by simple majority and in case of a tie, the army commander’s vote is decisive, which gives President Aoun significant control over the council.

Indeed, presidential leverage extends to civilian oversight over the military. While the 1989 Taif Agreement shifted civilian command of the military from the president to the Council of Ministers, the Lebanese president is the chair of the Supreme Defense Council along with the prime minister as his vice chair. The remaining five members are the ministers of defense, foreign affairs, interior, treasury, and economy. The daily operations of the secretary general are run by a military officer who reports directly to the prime minister. Only the president is authorized to convene the Supreme Council; otherwise, the prime minister needs one-third of the vote to do so, which Hariri lacks in the current formation. The Supreme Defense Council met once last January since Aoun became president.

A third and last point of presidential leverage is the expected synergy between the current Defense Minister Yaacoub al-Sarraf (close to Emile Lahoud) and General Joseph Aoun. The last defense minister, Samir Moqbel, was outmaneuvered many times by former Army Commander General Jean Kahwaji, including when Kahwaji enforced the decision to appoint his cohort Brigadier General Edmund Fadel as head of military intelligence. Once Fadel retires in a few months, President Aoun will have yet another opportunity to appoint a loyalist in one of the most crucial intelligence agencies in the security establishment.

The Internal Security Forces

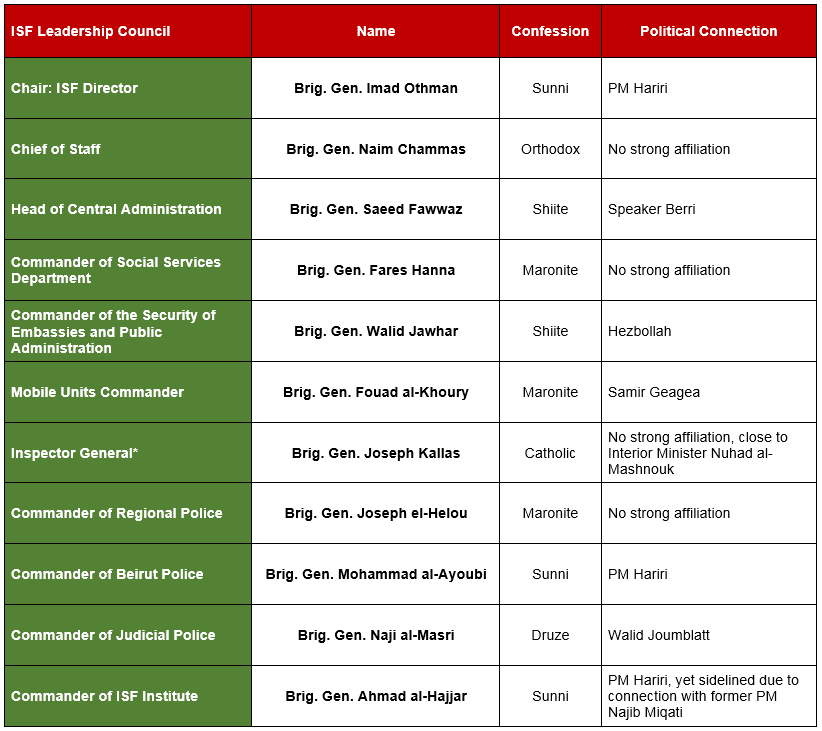

The assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri in 2005 and the subsequent withdrawal of Syrian forces from Lebanon altered the balance of power in the Lebanese security establishment. The three ISF directors since then have been loyalists of the Future Movement: Ashraf Rifi, Ibrahim Basbous, and now Imad Othman. The emergence of the Information Branch as a potent and independent Sunni-led intelligence force reflects that new dynamic.

Since then, the Information Branch even earned the trust of Hezbollah by playing a key role in unraveling Israeli networks and agents operating in Lebanon. Othman, who served as head of the Branch since October 2012 (after the assassination of his predecessor, Wissam Hassan), now leads the ISF. A new memorandum (AR) last year stated that the Information Branch now directly reports to the ISF director, which likely means that the clout of the branch will return to normalcy compared to its oversized role under Wissam Hassan.

The second expected breakthrough is the resumption of the ISF leadership council meetings after a period of dysfunction and inactivity since 2007, due to infighting among the oligarchy to replace more than half of the eleven members whose terms had expired. Now the council is fully staffed (see table below).

*All commanders report to the ISF Director except the inspector general, who reports to the Interior Minister.

The powers concentrated by law in the hands of Othman will provide enough leverage for Hariri to have a dominant role in the ISF. The challenge for Othman is to revitalize a fragile institution and counter the remaining influence of Ashraf Rifi, who is quietly challenging the détente between the Future Movement and Hezbollah. Hariri’s team hopes to amend the ISF leadership council’s internal procedures and cut its size to make it the centralized core of internal security; however, there is no indication yet if that scenario will materialize in the foreseeable future.

It is worth noting that Othman’s significant influence on internal security agencies does not extend to the Shiite-led General Security and Christian-led State Security. The General Security’s role expanded since 2005, when it became part of the Shiite quota of security positions, and it reports directly to the interior minister. Abbas Ibrahim’s role is widely recognized among the oligarchs and he is occasionally tasked by Hezbollah to play political roles. Most recently he mediated the rapprochement between President Aoun and Speaker Berri.

While technically the State Security directorate serves as an arm of the Supreme Defense Council, its role has been controversial in recent years. The last director, Brigadier General George Qar’a, sought to expand the authority of his directorate under the banner of restoring Christian influence. The reaction was swift—cutting the funding and marginalizing State Security—and this led to sectarian tensions. The recent appointment of Brigadier General Tony Saliba (close to President Aoun) as the new director helped to mitigate the bureaucratic infighting, but the issue might need further clarification. While reports are suggesting that the role of State Security will be neutral moving forward, with a focus on protecting state institutions and preventing public corruption, the first statement by Saliba after taking office offered an ambitious agenda of countering both Israel and radical terrorism.

Final Thoughts and Future of US Military Aid

Politics have molded the security establishment for decades. In the early 1970s, the late President Suleiman Franjieh purged the military officers affiliated with his predecessor, Fouad Chehab. Michel Aoun, as head of the interim government and army commander in the mid-1980s, distrusted the senior officers and asked younger officers to report to him directly. The Syrian regime subdued the security establishment for nearly a decade by giving preference to those loyal to Damascus while the dominant role of Hezbollah, as an armed group, has undermined these institutions’ core mission of monopolizing the use of force.

Since 2005, the repetitive disregard of hierarchy and seniority in making appointments has demoralized these institutions and their high-ranking officers. The army commanders in the last 15 years have imposed that same policy by making staff transfers that ensure their loyalists are de facto heads of certain departments. At present, the synergy between the president, defense minister, and army commander should reflect positively on the armed forces instead of continuing the same trend where respecting hierarchy and seniority is the rule and not the exception. A small and mobile ground force, like the army in Lebanon, cannot afford to have a large base of idle senior officers; hence altering the seniority and hierarchy or extending the age of retirement are not the right path moving forward.

On the ISF side, purging high ranking officers is a recurring policy that existed under Syrian rule and will likely continue. Furthermore, sectarianizing the internal security agencies is disconcerting and could gradually turn them into paramilitary forces. The relatively young age of the security leaders means that they will stay in their positions for at least six years. There is an urgent need to streamline these military and security agencies to make them more effective and relevant to today’s challenges without overlap and lack of coordination. Having a body that synchronizes both military and security agencies could serve that purpose while ensuring information exchange.

US diplomats and military and intelligence officials have working relations with LAF, ISF, and General Security. The appointments are not expected to have impact on US security aid and relations with Lebanon; the White House’s cuts in foreign aid, however, can be more damaging in that regard. In the past weeks, congressional and military delegations visited Beirut, though no US officials from the White House or State Department are expected anytime soon.

However, these security appointments reaffirmed the fact that Washington has limited space to maneuver the increasingly complex Lebanese politics. Furthermore, halting US military aid will not only undermine Lebanon’s stability and its ability to fight radical terrorism, but will also weaken the remnants of US influence in the country. The Lebanese security establishment is leading one of the most successful regional campaigns against radical terrorists, but the greatest danger it faces is the sectarian tendency that is undermining loyalty for national institutions. What the Pentagon can do is to encourage LAF commanders to further professionalize the military.

In the largest context, President Aoun’s comments last month that Hezbollah “complement” the Lebanese army raised concerns in Washington. However, that statement should come as no surprise. LAF, ISF, and the Information Branch all coordinate with Hezbollah, whether at the borders with Syria and Israel or in areas held by Hezbollah. No senior military or security officer in Lebanon can function or sustain his job without having a minimum working relationship with Hezbollah. Forcing the Lebanese military and security agencies to block Hezbollah or not to cooperate with the group is a recipe for political instability in the current political environment.

While the United States did not provide basic support for Lebanese allies attempting to deter Hezbollah between 2005 and 2008, it should not expect the Lebanese security establishment to play that role while the country is struggling to cope with the spillover of the Syrian war. In the absence of a clear US regional policy beyond defeating ISIL, withdrawing US military aid will most likely push Lebanese security agencies into the arms of Iran.