Iraq’s parliamentary elections last May exposed serious flaws in the country’s political process. Doubts abounded about the credibility and legitimacy of the results because of widespread accusations of fraud, corruption, and vote rigging and buying. Traditional Iraqi politics showed a marked inability to secure transparency and a smooth transfer of power, or to respond to public demands for genuine political change. The elections also displayed the impact of 15 years of single-party rule––of the Shia Islamist Daawa Party––since the American invasion in 2003.

The elections were followed by an arduous process of choosing the three constitutional officers of the Republic of Iraq: president, prime minister, and speaker of parliament. This system has suffered from longstanding troubles besetting the country’s political fortunes including domination of religious parties, factional interests, confessional and ethnic divisions, and lack of accountability. Outgoing Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi—despite high hopes for him in 2014—has failed to curtail the ill effects of the rule of his predecessor Nouri al-Maliki, leaving Iraq without the necessary mechanisms and prospects for effective governance.

What has been clear since 2003, notwithstanding the partnerships between different political factions and blocs, is that Iraq’s prime minister has had vast control over the instruments of power and influence

What has been clear since 2003, notwithstanding the partnerships between different political factions and blocs, is that Iraq’s prime minister has had vast control over the instruments of power and influence. Through his de facto stewardship of the armed forces and security services, the parliamentary majority, financial patronage networks, and the courts, the prime minister became the arbiter of all political machinations in the country, as was evident during the eight-year rule of Nouri al-Maliki.

Concomitant with this role has been the sidelining of the president of the republic in all domestic and external affairs, rendering that post as a mere figurehead with little executive authority. This is in contrast to the directive of the Iraqi constitution, which states that the executive branch is composed of the president and the prime minister and executive departments. It gives the head of state essential functions such as choosing the premier, approving international treaties, issuing decrees, and naming ambassadors, among other duties.

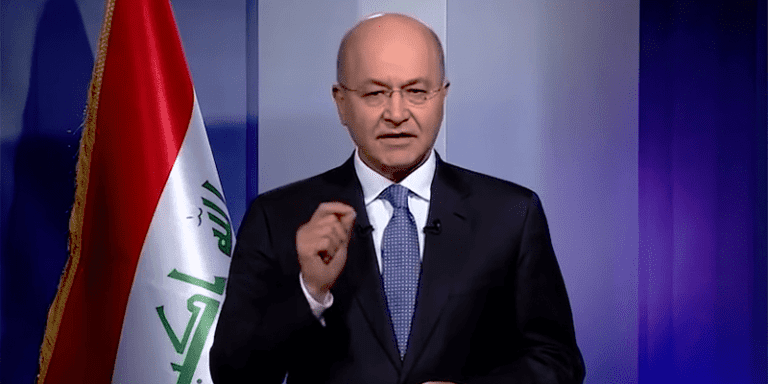

It is in this context that the election of Barham Salih––nominated by the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan––as president of Iraq to succeed Fuad Masum is seen as a positive step. Parliament elected him with a margin of 219 to 22 against a challenger from the Kurdistan Democratic Party after a bitter dispute that could have serious future repercussions for Kurdish unity. Salih immediately nominated Shia politician Adel Abdul-Mahdi for the post of prime minister, in effect ending the career and prospects of former Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi.

The elements of Iraqi President Salih’s political identity have endeared him to Iraqis and helped in gaining their trust that he will steer the ship of state on a right course and preserve Iraq’s independence and sovereignty

Salih’s election was warmly received by wide sectors of Iraqi society. Although he still has to prove that he is a unifying figure and will emphasize his Iraqi nationality instead of his Kurdish ethnicity, he enjoys certain characteristics that have allowed him to secure the support of members of parliament—despite avowals by faction leaders to throw their weight behind his opponent. He is also well-versed in political and international affairs, has a doctorate from a British university, lived and worked in the United States, and refused to support the ill-fated 2017 Kurdish referendum to secede from Iraq. These elements of Salih’s political identity have endeared him to Iraqis and helped in gaining their trust that he will steer the ship of state on a right course and preserve Iraq’s independence and sovereignty.

The choice of Adel Abdul-Mahdi as premier was possible because of the dispersal of Shia political power and the rise of non-sectarian and non-ethnic electoral lists in the recent elections

Salih’s choice of Adel Abdul-Mahdi as premier was a departure from political tradition, as the job has usually been conferred on the leader of the largest parliamentary bloc. Abdul-Mahdi is a moderate who does not lead a sizable faction; for the stability of his putative cabinet, he will depend on a coalition between the Moving Forward bloc of cleric Muqtada al-Sadr (54 seats) and the Victory bloc of outgoing Prime Minister Abadi (48 seats), plus a number of independents and Kurdish parliamentarians. The choice of Abdul-Mahdi was possible only because of two inherent conditions: first, the dispersal of the power of the Shia voting bloc among a number of factions so that not one could claim to represent an overarching political actor; and second, the rise of non-sectarian and non-ethnic electoral lists that were able to garner support from wide sectors of Iraqi society. In any case, Abdul-Mahdi will be one pillar of a new order in Iraq composed of himself, President Barham Salih, and Speaker of Parliament Mohammed al-Halbousi, who is a newcomer to politics.

With Salih assured of his position as a unifier of Iraq’s disparate political tendencies, it will be essential that Abdul-Mahdi formulate a strategy for executive authority to succeed in facing Iraq’s many challenges. He is known to eschew the limelight and avoid confrontation—in a country rife with daily confrontations. His lack of effectiveness in building a strong political constituency to match other Shia politicians may indeed doom his premiership; to be sure, present-day Iraq needs someone to revive its state institutions and end the dominance of religious parties over its resources. In other words, Abdul-Mahdi needs to develop the skills of political combat quickly because his success will depend on his effectiveness in fighting corruption and ending the control of religious forces.

While present conditions in Iraq continue to point to political instability, given the disarray among factions and the fragility of the government formation process, there are some encouraging signs of positive changes to come:

- Eighty-two percent of Iraq’s new members of parliament are newcomers to the chamber, which indicates that they may not hew to the old political habits that produced the culture of double-dealing and corruption that has prevailed since 2003.

- The increase in the price of oil will add to the government’s coffers and allow serious spending on poor-performing public sectors, thus improving the general public’s mood and cooperation with government institutions.

- Increasing public pressure from protests and demonstrations in the central and southern governorates has forced the weakened religious parties to recede partially, thus diminishing their control. This is also the case in the Kurdish north where voter participation in parliamentary elections in the Kurdistan region was very low, indicating dissatisfaction with local political conditions.

- There has been a decline in Iran’s influence among traditionally pro-Iranian sectors of Iraqi society and politics. The burning of the Iranian consulate in Basra during recent public protests has sent a message that Iran’s ability to control events in Iraq may have declined, and with it Iran’s readiness to provide financial support to its friends there. This is especially significant in light of the fact that the Islamic Republic will soon have to deal with renewed American sanctions, set to begin in early November.