On February 9, the US Senate commenced the second impeachment trial of former President Donald J. Trump to examine his role in inciting the January 6, 2021 riot at the US Capitol complex. The House of Representatives actually voted to impeach then-President Trump on January 13 for engaging “in high crimes and misdemeanors by inciting violence against the government of the United States.” However, the House waited to deliver the article of impeachment to the Senate for another 12 days, January 25, because of Senate majority leader Senator Mitch McConnell’s (R-Kentucky) desire to postpone the trial until January 19, just a day before Trump left office. New Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-New York) and McConnell agreed to delay the start of the Senate’s trial by about two weeks to allow for Trump’s legal team—one that has undergone a series of major changes—to prepare the former president’s defense.

Even after the pair finalized the framework governing Trump’s second impeachment, there are a host of unanswered questions about the constitutionality of the whole process, how long the trial will last, and whether witnesses will be called to testify before the Senate. As an unprecedented second presidential impeachment trial gets underway, it is important to explore its process and procedure.

Timing and Procedure of Second Impeachment Trial

The Senate’s fourth presidential impeachment trial will quite possibly be the shortest of such trials on record. President Andrew Johnson’s 1868 impeachment trial lasted nearly 12 weeks, President Bill Clinton’s trial in 1998 lasted five weeks, and even President Trump’s first impeachment trial in 2020 lasted about three weeks. According to the information available at this time, this latest impeachment trial could last approximately one week.

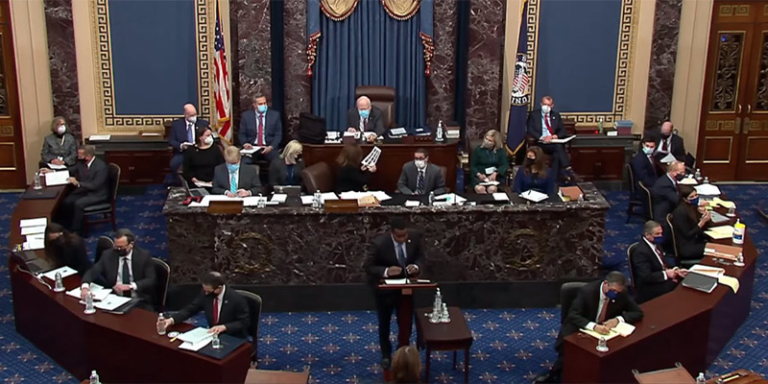

Procedurally, Senate impeachment trials have generally followed the same rough parameters. For example, the agreement that Senators Schumer and McConnell have reached reportedly preserves characteristics of previous impeachment trials such as affording the nine-person impeachment management team and Trump’s defense team each several hours to make their cases before the Senate. In other ways, this trial will also operate differently. Because President Trump is no longer in office, Chief Justice John Roberts opted not to oversee the trial, leaving that task instead to Senate President Pro Tempore Patrick Leahy (D-Vermont).

Here is an outline of the relevant dates and actions of the latest impeachment trial:

January 13, 2021 – The House voted to impeach President Donald Trump for the second time.

January 25, 2021 – House impeachment managers delivered the article of impeachment to the US Senate.

January 26, 2021 – Senators, who serve as jurors for impeachment trials, were sworn in for that purpose. Later, the Senate voted 55-45 to reject a motion by Senator Rand Paul (R-Kentucky) to dismiss impeachment proceedings against Trump.

February 2, 2021 – The Trump legal defense team and House impeachment managers both submitted the necessary briefs. The Trump team submitted a brief answering the charges outlined against Trump in Congress’s article of impeachment. The House impeachment team submitted their own brief, outlining their case against the former president in a trial memorandum.

February 8, 2021 – Deadline for the Trump legal team to submit its own pretrial brief, outlining its arguments in defense of the former president against the charges laid out by House managers. In addition, the House impeachment team had to submit a replication—or response to the plaintiff—to the Trump team’s original answer to his impeachment charge.

February 9, 2021 – Deadline for House impeachment managers to submit a rebuttal to the pretrial brief submitted by Trump’s legal team. This date formally marked the beginning of the Senate impeachment trial, though Senators Schumer and McConnell had agreed to allow for senators to debate and vote on the constitutionality of trying a former president for high crimes and misdemeanors, before moving on to the argument stage of the process. In the end, the majority of the Senate voted 56-44 to uphold the constitutionality of the current impeachment trial.

February 10, 2021 – At 12:00 noon, the Senate convened to hear oral arguments from the nine-person House impeachment team and from the legal team representing Donald Trump. Each of the two sides has up to 16 hours—spread out over multiple days—to make its case.

February 12-14, 2021 – Originally, the Senate planned to break at around sundown on Friday in order to allow for observation of the Sabbath. However, the Trump attorney who requested the break later changed his mind, so the Senate is set to continue with the trial on Saturday, possibly continuing on Sunday.

TBD – Sometime during the week of February 15, oral arguments will conclude and the House impeachment team will have the opportunity to propose calling on witnesses for testimony. As of now, it does not appear that impeachment managers intend to call witnesses, but if they do choose to do so, the Senate would vote on which witnesses to call to testify.

TBD – If no witnesses are called, senators will be given time—likely up to two days—to ask questions of both the impeachment and defense teams.

TBD – In the end, senators will vote on whether to convict former President Trump of inciting violence against the US government. If—and only if—the Senate agrees to convict Trump, Democrats would then motion to vote on a measure barring Donald Trump from holding public office ever again.

Prospects for the Impeachment Trial

The abridged timeline of Trump’s second impeachment trial reflects the near certainty that the former president will be acquitted for allegedly inciting violence against the US government. If the entire Democratic caucus sticks together and votes to convict him, those members will still need the support of at least 17 Republicans to reach the 67 votes necessary to convict Trump. If early votes are any indication, Congressional Democrats might have the support of only five of their Senate Republican colleagues.

The overwhelming majority of the Senate Republican caucus is responsive to the Trump defense team’s argument that the whole impeachment trial is unconstitutional due to Trump’s current status as a private citizen. It is evident that members have not truly grappled with the nature of the charges levied against Trump, simply writing off the whole process as inherently flawed or possibly even unconstitutional. This position illustrates the likelihood that no amount of information or testimony will change these members’ minds on the matter. As such, it appears that House impeachment managers are focusing on putting forth an argument based on publicly available information about the January 6 capitol riots.

Because members of Congress were present on Capitol Hill and were witnesses to the violence and chaos that took place that day, House impeachment managers may feel they do not need to call any other witnesses to make their case. But even if they do choose to bring in outside witnesses, the legal battles that could unfold—this threat loomed large during Trump’s first impeachment trial—would take a prohibitively long time to address. Furthermore, Senate Republicans have vowed to pursue a wide range of witnesses if Democrats vote to allow witnesses to testify. Senate Democrats are conscious of the time-consuming nature of impeachment trials and, because they want to use this precious time to pass a COVID-19 stimulus package and confirm President Joe Biden’s cabinet, they do not seem eager to pursue long, drawn-out fights over witnesses, especially if one takes into consideration that witness testimony would appear to have little influence on GOP senators’ willingness to convict Trump.

In all likelihood, the Senate impeachment trial will not feature any outside witness testimony and it is probable that the Senate will fail to reach the 67-vote threshold necessary to convict Donald Trump for his alleged high crimes and misdemeanors. An acquittal would also strip the body of the ability to pass, with a simple majority, “the additional consequences provided by the Constitution in the case of an impeached and convicted civil officer” (i.e., permanent disqualification from elected or public office).

Prospects for Donald Trump’s Political Future

It is no secret that Donald Trump remains a force in the Republican Party and that he has signaled his desire to run for president again in 2024. A failed conviction would not only leave the door open for his return to national politics, but it could perhaps even embolden the one-term president. However, some legal scholars argue that conviction, with its subsequent punishment, is not the only remedy available to lawmakers seeking to bar him from holding such a high office. Two legal experts argue that Congress could pass concurrent resolutions through both the House and Senate, by a simple majority, prohibiting Trump from running for office again in the future. The move is predicated on a reading of the post-Civil War 14th Amendment to the US Constitution that bars public officials from office for acts of “insurrection or rebellion.” Of course, such a move would likely invite legal challenges—and there is no way to know how the courts or the Supreme Court would rule on them—but the law plainly states that prohibitions against holding public office can only be overturned by an act of Congress with super-majority (i.e., two-thirds majorities) support in both chambers.

There are other arguments that posit that section 3 of the 14th Amendment does not allow Congress on its own to declare a former president ineligible for public office. Any legal action by Trump challenging such a decision would invite legal scrutiny to which the former president might not be willing to submit. Ultimately, it is legally unclear whether former President Trump will be able to pursue his old office in the future. With his impeachment trial looking more and more likely to result in acquittal, holding Trump responsible for his alleged role in inciting the mob violence on the capitol on January 6 becomes less certain with time.