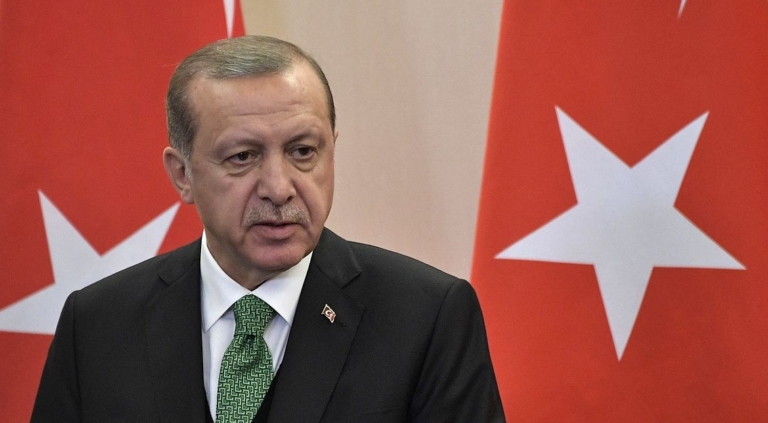

Despite historically low approval ratings, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is a firm believer in his skill as a negotiator and in his country’s exceptional status in international politics. In Erdoğan’s worldview, outward inconsistencies are harmonized with the thesis of “Turkish exceptionalism,” which holds, among other things, that Turkey may act independently as an exceptional NATO member, that it could be part of the European Union while still embracing an anti-western discourse, and that it should be able to obtain American military assistance while carrying the flag of resistance against the United States. Erdoğan has a deep belief that such strategic maneuvers are effective. As he proclaimed in a 2021 speech to provincial heads of his Justice and Development Party (AKP), “We are closer than we have ever been in the past two centuries to a Turkey that is politically reputable, and has a strong economy and a wide area of social and cultural influence in its region and the world.” A steep decline in the value of the Turkish lira indicates Erdoğan’s detachment from everyday reality. However, the diplomatic arena still offers the Turkish president an opportunity to fulfill his dreams of standing in the global spotlight.

A July 2022 meeting in Tehran between Turkey, Russia, and Iran epitomized Erdoğan’s vision of foreign policy. On the one hand, Ankara has enabled Moscow to show its ability to shape Middle East politics, despite Russian President Vladimir Putin’s so far limited progress in the prosecution of his war on Ukraine. This posture was highly significant not only for Russia but also for Iran, especially at a time when US President Joe Biden was conducting high-level meetings in the Middle East. On the other hand, the Turkish government has packaged the trilateral meeting as being demonstrative of Turkey’s strategic value to the West, chiefly because Turkey helped broker a deal to resume grain shipments out of war-torn Ukraine, which brought it high praises from the United Nations for having helped avert a global food crisis.

Vulnerabilities that Bind Moscow and Ankara

Many analysts find it perplexing to watch Erdoğan’s pivot to Russia, which comes immediately after his efforts to reconcile relations with Turkey’s NATO allies in the past year. Following the Tehran summit, Erdoğan met with Putin in Sochi, ushering in an era of accommodation in bilateral relations. The Russian economy, which has been crippled by western sanctions following the invasion of Ukraine, desperately needs a lifeline. And the strained Turkish economy cannot afford to lose Russian energy supplies, which make up about 45 percent of Turkey’s natural gas and 25 percent of its crude oil imports. Clearly, economic woes in both Russia and Turkey incentivize a deepening of financial ties between the two countries, an action that may have long-term implications.

Clearly, economic woes in both Russia and Turkey incentivize a deepening of financial ties between the two countries, an action that may have long-term implications.

Turkish officials are now boasting that exports to Russia have reached their highest levels since 2014, while Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak has spoken of growing fiscal ties between the two countries. Erdoğan, meanwhile, has expressed his hopes of seeing economic cooperation that could reach a total of $100 billion. In addition, Erdoğan has also signaled a broader strategic vision by announcing that Turkey will attend the September 2022 meeting of China’s Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

The new agreements also include a striking development, namely major Turkish banks’ adoption of Russia’s Mir payments system. By paying a portion of its substantial annual energy bill in Russian rubles, Turkey will further deviate from western countries, most of which have refused to pay Russia in rubles in order to keep sanctions against Moscow effective. In return, Ankara is seeking short-term benefits that would help ease troubles related to Turkey’s foreign reserves. With Putin’s help, a cash injection by Russia’s state-owned nuclear corporation Rosatom into a Turkish subsidiary was organized, resulting in the greatest rise in Turkey’s official reserves in the past six months. Turkish officials are hoping to witness an additional transfer of $15 billion to complete the construction of the Akkuyu nuclear power plant, which is Turkey’s only large nuclear plant, and which will be a boon for the country’s energy strategy and for Erdoğan’s political fortunes. But more important is boosting the value of the lira. Therefore, even though Turkey has received some cash injections from the Gulf, Erdoğan still has his eyes on the prize that he hopes may arrive from Moscow.

Even though Turkey has received some cash injections from the Gulf, Erdoğan still has his eyes on the prize that he hopes may arrive from Moscow.

A Green Light for Military Operations in Syria?

Together, the Sochi meeting and the preceding summit in Tehran revealed the limitations of Turkish-Russian negotiations over Syria. Many were on the lookout for potential transactional arrangements that would facilitate Turkey’s military operations in northern Syria. Although Russia is allowing increased Turkish drone attacks against Kurdish fighters, cutting a deal for another Turkish incursion will not be an easy achievement for Erdoğan. Following the Tehran summit, Russia increased airstrikes in Syria’s Idlib Governorate, undoubtedly to remind everyone that it possesses the ultimate leverage in Syria. Under the current circumstances, the status quo is in favor of Russia, which has threatened to close the Bab al-Hawa humanitarian aid corridor in Idlib, causing a new wave of refugees coming into Turkey. Given these developments, why should Putin allow Erdoğan to gain more territory? And what are the potential incentives that may be offered to Russia from the Turkish side?

Putin may be willing to permit a limited military operation to help Erdoğan’s electoral campaign, as long as the latter repays the favor. According to Ukrainian intelligence officers, Putin is demanding that Erdoğan allow Russia to buy stakes in Turkish oil refineries and reservoirs, which would help disguise the origin of Russian energy exports after the EU instituted an embargo, the full extent of which is expected to be reached by early 2023. Another demand from the Kremlin is the creation of correspondent accounts between Turkish state-owned banks and Russian banks that are under EU and US sanctions. So far, there is no evidence that Erdoğan has accepted any of these demands, and doing so would put him under severe pressure by the West for sanctions-busting, bringing additional risks to Turkey’s fragile economy.

However, an alternative Russian demand that Turkey engage in direct talks with Syria’s Assad regime may be under consideration by Erdoğan’s government as an incentive to Moscow. Putin wants to support his ally Bashar al-Assad’s international standing, and Erdoğan’s initiation of direct talks with Damascus would boost the Syrian regime’s legitimacy. Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu recently announced that he met with Syrian Foreign Minister Faisal al-Mekdad and that the two countries’ intelligence officers have been in direct communication over the past few months. Çavuşoğlu’s stated that Turkey needs to find a way to “get the opposition and the regime to reconcile in Syria. Otherwise, there will be no lasting peace.”

Çavuşoğlu’s statements have shaken the atmosphere in Turkey. And in Turkish controlled territories of northern Syria, mass protests were organized and Turkish flags were torn down, indicating the confusion and fear felt by many Syrians. Meanwhile, the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army denounced any attempt at reconciliation with the Assad regime as a “betrayal” and warned that it would mean “handing the region over to chaos and destruction.”

Direct Talks with Damascus on the Horizon?

Although Ankara has not yet committed to any bilateral meetings with the Assad regime, the Turkish government’s public announcement that it is considering all options is indeed an important development. A number of factors may lie behind Erdoğan’s consideration of direct talks with Damascus. First, Erdoğan’s accommodation of Putin on this matter will not necessarily require Ankara to engage in meaningful negotiations with the Assad regime. Even if these talks are meant to be empty public displays that will elevate Russia to the role of broker and allow Damascus to appear as a legitimate representative of the Syrian people, Erdoğan may expect payback from Putin, perhaps including a green light for a limited military operation that will support the Turkish president’s electoral campaign.

Second, the Assad regime is already being legitimized as a result of policy changes in the Gulf, and specifically in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. The Turkish government’s steps in this direction may therefore be seen as positive by Gulf states that aim to curb Iran’s influence over Damascus. To put it simply, Erdoğan may sell this move to the Gulf as well, given that Turkey is still negotiating with Saudi and Emirati officials over financial assistance.

Third, Erdoğan is testing the waters for his domestic calculus. As an election campaign strategy, Turkish opposition leaders have expressed their plans to send all Syrian refugees back to their homeland. From the outset, it seems contradictory for the Turkish government to make threats of military action in northern Syria while simultaneously becoming engaged in direct talks with the Assad regime over a return of refugees. But in the eyes of Erdoğan the politician, however, it makes perfect sense; Erdoğan is aiming to send a message to the Turkish electorate that he is going to do whatever is needed—whether waging war or making peace—to resolve the refugee issue. Erdoğan ultimately wants to be seen as a pragmatic and populist leader, rather than a rigid and ideologically circumscribed one.

Erdoğan is aiming to send a message to the Turkish electorate that he is going to do whatever is needed—whether waging war or making peace—to resolve the refugee issue.

Finally, Ankara’s direct talks with the Assad regime may hamper relations between Damascus and the Syrian Kurds, especially since Turkey is offering a new version of the Adana agreement—signed between Ankara and Damascus in 1998 against the activities of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)—to also contain the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the PKK’s affiliate in Syria.

A policy shift to initiate direct talks with Damascus has serious risks as well. Former Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, the architect of Turkey’s Syria policy during the initial years of the Syrian civil war, protested plans to grant legitimacy to the Assad regime for the sake of accommodating Putin. Davutoğlu thinks that direct talks with the Assad regime would only exacerbate the refugee problem, as Syrians would be alarmed about Turkey’s “selling them out,” resulting in another major wave from Idlib to the Turkish border gates.

Will Washington Accept Turkish Exceptionalism?

Erdoğan’s attempt to play both sides of the Ukraine war has been a matter of controversy in US policy circles, including in Congress. Turkey’s free-rider approach is often tolerated by those who perceive Turkey as indispensable for NATO due to its geopolitical location. This traditionalist perspective stems from the Cold War, when containment of the Soviet empire was the highest priority. In fact, traditionalists typically buy into the idea of Turkey’s exceptionalism given both Turkey’s unique location as the bridge between Europe and Asia and its symbolic significance as a country combining Islam and secularism. They believe that Erdoğan’s dealings with Putin should be accommodated, and emphasize what they see as the value of a NATO member state that is able to reach Putin with closer ties. Moreover, in their view Turkey is more than just the current Erdoğan regime, and there is therefore hope of reviving a strategic partnership with Ankara in the future.

Opposing the traditionalist camp are revisionists who contend that a policy of appeasement with Erdoğan’s government will never work. The revisionist camp is also pessimistic about Turkey’s future alignment in the post-Erdoğan era. They argue that structural shifts in the international order have rendered the Turkish-American strategic alliance permanently defunct—a fact best reflected in the two countries’ troubled relations over Iraq and Syria during the post-Cold War era. They therefore argue that the United States should accept the reality that Turkey is no longer a strategic partner, and that Washington should search for alternatives to replace Turkey by improving closer military ties with Greece and Cyprus. Accordingly, the Turkish government’s breach of NATO expectations should not be tolerated, and if needed the United States should use firm measures and financial sanctions to shape Ankara’s behavior.

Erdoğan is treading a fine line as he negotiates with multiple international partners over issues that could shape both the fate of Turkey and that of his own presidency.

These two competing perspectives, the traditionalist and the revisionist, will shape Washington’s response to developments in the relationship between Erdoğan and Putin. Given resistance from Congress, the Biden Administration is unlikely to push ahead with efforts to sell fighter jets to Turkey, which was undoubtedly meant as a way to influence Turkey in case financial ties between Russia and Turkey quickly grow. If ties between the two countries do end up evolving into a scheme to save Moscow from international sanctions, the White House will certainly face even harder choices. Erdoğan is thus treading a fine line as he negotiates with multiple international partners over issues that could shape both the fate of Turkey and that of his own presidency. It remains to be seen, however, if his brinksmanship will succeed, or if it will ultimately end in disaster.