Waiting for President Donald Trump’s “ultimate deal” for Middle East peace is like waiting for Godot in Samuel Beckett’s play. For two years the world has patiently stood by, expecting the two main characters, Middle East envoys Jared Kushner and Jason Greenblatt, with assistance from the US Ambassador to Israel David Friedman, to deliver their “deal of the century.” The president assured the world on September 26, 2018—for the umpteenth time—that his long-anticipated peace plan for Israel and Palestine would be released within a few months. It would be folly to run to the nearest bank with the latest empty promissory note; but what if Trump indeed delivers in early 2019?

The following is a set of responses by analysts from Arab Center Washington (ACW) and its Academic Advisory Board to questions about the impact of such a proposed deal and the possible reactions to it by Palestinians, Israelis, Arab states, Americans, and the international community.

What are the true costs of the ultimate deal?

Tamara Kharroub

Based on the reported parameters of the Trump Administration’s peace plan, this highly anticipated deal is expected to break not only with decades of US and international policy toward Palestine and Israel, but also with international law, UN conventions, and humanitarian principles. Over the past year, Trump’s policies included moving the US embassy to Jerusalem (thus breaking with longstanding international consensus and commitments and condoning the use of force and occupation); cutting funding to the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA), the Palestinian Authority, and lifesaving hospitals serving Palestinians (and with that, exacerbating the humanitarian crises facing Palestinians, particularly refugees); and choosing not to condemn illegal settlements (consequently opening the door for more settlement building in the occupied territories). In addition, reports indicate that the US Agency for International Development’s (USAID) much-needed development projects in the West Bank and Gaza would shut down in 2019.

All of these actions, along with the Trump Administration’s “peace deal” that would allow Israel to annex large parts of the West Bank (including existing settlements, East Jerusalem, and the Jordan Valley), violate United Nations Security Council Resolution 242, on which the two-state solution was based. Resolution 242 was unanimously adopted by the Security Council in 1967, “emphasizing the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war,” affirming that the establishment of a just and lasting peace “should include” Israeli withdrawal from territories occupied in 1967, and calling for “achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem.” Trump’s peace plan undoubtedly violates these accords. As for the right of return of Palestinian refugees, the Trump Administration seems intent on unilaterally terminating this internationally recognized right. However, attempts to force a deal that takes away the Palestinian refugees’ right of return without repatriation or compensation would be a direct violation of international law.

These shifts and precedents in US policy toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have set the stage for other international players to follow suit; indeed, they are now emboldened to prioritize their economic and military interests and their power-hungry agendas over the principles of human rights and international law. The start of this trend was evident with some Arab and African nations normalizing relations with Israel and with emerging populist regimes in Eastern Europe and Latin America taking advantage of the Trump effect and expressing their intent to move their embassies to Jerusalem while condoning Israeli violations and war crimes.

What are the likely reactions of the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Israel if the deal is announced?

Yousef Munayyer

How the PA and Israel will respond to any Trump Administration proposal will ultimately depend on what is in the details. Of course, given what we have seen from the Trump Administration thus far and the positions staked out by the key team members formulating the proposal––Kushner, Greenblatt, and Friedman––it is hard to imagine anything in it that could be fair to the Palestinians. In fact, as a result of the administration’s overt bias toward Israel overall and its loss of international legitimacy as a peace broker, the Palestinian Authority will most likely be compelled to reject whatever the Trump team puts forward. This could be radically changed if Trump ultimately surprises the world and proposes something fairer than his posture over the past two years has suggested.

The Israeli government is very likely to be supportive of anything Trump proposes, particularly given the warmth of its relationship with his administration since its early days. One possible component of Trump’s deal that could prove challenging for both sides is if it dangles the prospect of American recognition of a Palestinian state at some defined or undefined point in the future. However, it is hard to expect Israeli lawmakers, whose governing coalition includes parties opposed to a Palestinian state at all costs, to accept a deal that includes such a prospect. Simultaneously, they run the risk of the international blame game that inevitably follows all of these proposals if they reject a plan from the most pro-Zionist administration in American history. For the PA, this, too, is a dangerous trap. It has long sought recognition of Palestinian statehood internationally, so rejecting it would be quickly spun as a “missed opportunity.” But the PA has also learned that the promise of statehood and the actual ability to exercise sovereignty are two very different things. In accepting such a proposal, it would continue to be complicit in providing cover for the status quo with no guarantee of a path to achieving its goal. Additionally, by going along with Trump, the PA would also sacrifice what little remaining legitimacy it had gained by rejecting his positions over the past two years.

If American recognition of a Palestinian state were to be presented in the Trump peace plan, both sides would have difficult choices to make and would likely accept the proposal with reservations. But this would not create a foundation for moving a process forward because of deep distrust and lack of interest in making real progress. Instead, this situation would likely remain stalemated, leading to reengaging in the blame game, one which Israel with its greater resources and connections is in a better position to win.

Can Trump deliver? What might the Arab response be?

Khalil E. Jahshan

My lack of excitement for Trump’s ability to deliver on his long-touted plan has a threefold explanation. First, the president’s agenda, both domestic and foreign, is quite full at this time. Few experts believe that he has the attention span and presence of mind to focus on this high-maintenance issue, at a time when he is facing the most existential crises of his two-year-old administration.

Second, the content of his “ultimate deal,” as leaked by its architects and fans, leaves little room for optimism, warm reception, and successful implementation in the Arab world and the region. The promised dependent and truncated Palestinian mini-state, without Jerusalem as its capital, without clearly determined borders, without the right of return for millions of Palestinian refugees, and above all, without a definitive end to Israeli domination and military occupation, all militate against an open-arm welcome by the Arab side. The Palestinians are essentially excluded from the process, depriving it of basic legitimacy in the eyes of those whose cause it purports to address.

Finally, in their lack of diplomatic experience and wisdom, the White House team mortgaged the process to specific Arab allies with the assumption that their role would likely maximize its chances of success and minimize US risks of its potential failure. These Arab countries, namely Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates, are too distracted by internal and regional crises to even care for Washington’s dictates at this time. Their regimes have shown some receptivity to US plans, but not at the expense of their own national security. Like it or not, according to the Arab Opinion Index 2017-2018, data show that public opinion in most of these Arab countries is overwhelmingly opposed (87 percent) to formal recognition of Israel. For Arab leaders, loyalty to Donald Trump and his peace deal minions is one thing; however, committing national suicide is totally another adventure.

What could be the American public and congressional response to the so-called deal of the century?

Laurie King

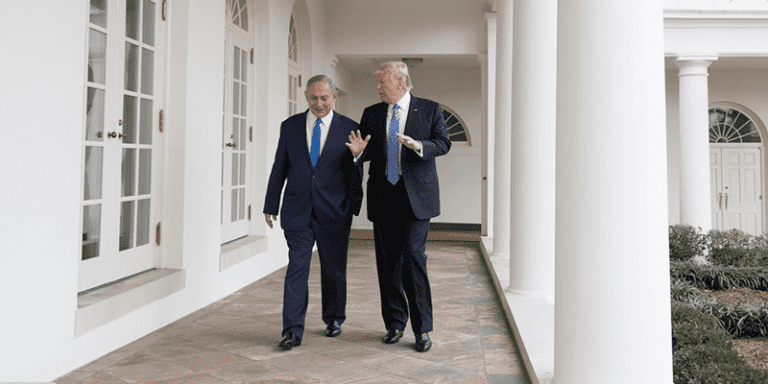

Without seeing the text of the deal, it’s hard to say. One can assume, however, that the views and interests of Jared Kushner will inform the deal, and as such, it will be viewed with skepticism by a large segment of Americans tired of the corruption in the Trump Administration—not to mention by many of the newly elected members of Congress, most notably Rashida Tlaib (D-Michigan) and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-New York). Given the Trump Administration’s reliance on and support of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and the clear and growing discomfort in the Senate with his role in the murder of dissident journalist and US permanent resident Jamal Khashoggi, the “deal of the century” might be met with uncharacteristic pessimism in the Senate and the House. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, a key supporter and beneficiary of any prospective deal, is facing his own problems with bribery charges and domestic issues in Israel and could well be out of office soon.

Sadly, most Americans are not very concerned about the state and fate of Palestinians, given pressing domestic concerns and a growing focus on Iran as a threat to the entire Middle East, not just Israel. The degree of this threat is questionable, but media and policy rhetoric keep it front and center in US discourses on Middle East policy. At present, the Palestinians do not have a clear and strong leadership to present their case forcefully to the US public and legislators. The primary actors in Palestine now are the brave young people protesting at the border fence between Israel and the Gaza Strip. It seems that there is more sympathy for their cause and suffering in the United States than usual, but many Americans are weary of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and there is a danger that wide swathes of the voting public have simply tuned out.

What is the international reaction to the deal likely to be?

Imad K. Harb

Considering the UN General Assembly votes over the last two years regarding the question of Palestine and Palestinian rights, it is unlikely that the anticipated Trump Administration plan for Palestinian-Israeli peace will receive much international approval or support. In fact, aside from Israel and a few small UN member states, the administration stands isolated on this issue, just as it did when President Trump declared Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and moved the American embassy there, or when he announced the American withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) regarding Iran’s nuclear program. On these issues and others, the international community is united in its adherence to international law prohibiting the acquisition of territory by military means and emphasizing respect for international agreements.

Since the deal has not yet been announced, no specific reactions to it have emerged from the European Union, Russia, China, or other countries. But these parties’ responses to Trump Administration pronouncements on Palestinian-Israeli issues show an obvious disagreement with current American policy on the Palestinians’ right to an independent state and on peace proposals that ignore Palestinians or advance Israel’s interests above others. The international community is committed to a just peace for all, one that is based on United Nations and UN Security Council resolutions since 1948. What can be gleaned as elements of the Trump Administration’s deal contradict these resolutions and promise to perpetuate both the unsustainable status quo of marginalizing Palestinian rights and discounting the conditions that lead to more instability in the Middle East.