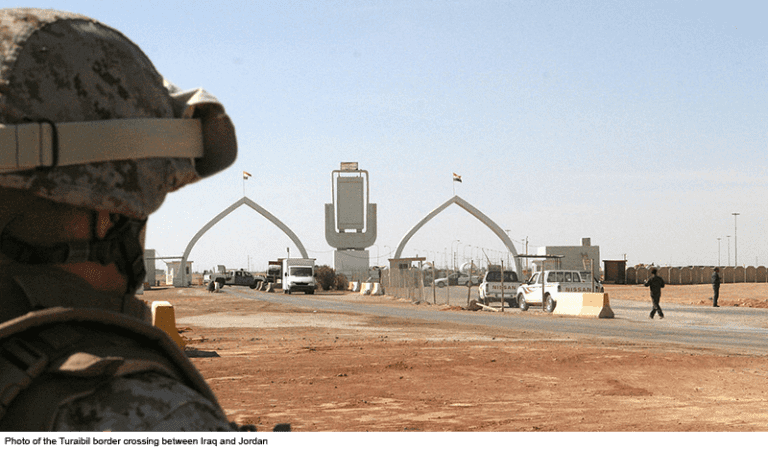

On August 30, the Turaibil border crossing that links Iraq with Jordan was reopened after two years of closure. Striving to recover from the devastation of the so-called Islamic State (IS), both the Iraqi and Jordanian governments are hoping to benefit economically from that key trade route. However, there are strategic, security, and logistical challenges that might stand in their way. Most importantly, the ongoing tensions between Washington and Tehran to determine who controls the Baghdad-Amman highway might destabilize the border and lead to further strife in Iraqi politics.

Iraq’s Highway 1 links the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries with Jordan and Syria. Beginning from the southern Umm Qasr port in the Basra Province, it runs in its final stretch through Baghdad, Fallujah, and Ramadi before reaching the key town of al-Ratba (the rear corridor to Turaibil) in the west. Once the 1,200-kilometer highway reaches al-Ratba, it splits into two roadways, one that goes into Syria (via the al-Waleed crossing) and one into Jordan.

Seized by IS in June 2014, Turaibil remained functional until IS captured al-Ratba in July 2015. During that interim period, truck drivers who traveled from Baghdad across the Jordanian border took the longer route (instead of the shortest via Ramadi and Fallujah), passing through the checkpoints of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) in Karbala before paying customs fees to IS militants. Since July 2015, the 549-kilometer road between Baghdad and Turaibil has been nearly lawless, most notably in western Anbar where IS has yet to be fully defeated. However, Iraqi forces, border guards, and the Iranian-backed PMF have been deployed recently as political tensions have been increasing in Iraq around the question of who will ultimately control that highway.

Washington Reverts to US Security Firms in Iraq

The Iraqi government’s decision last spring to award the contract for securing the Baghdad-Amman highway to the Olive Group reignited the debate about the role of US security firms in Iraq. The experience of US private military contractors in Iraq has been mired in challenges, most notably in the 2007 Nisour Square massacre when Blackwater security guards opened fire in a crowded traffic circle in Baghdad. The fact is that as long as mandatory military service is not restored by the US government, Washington will continue to rely on private military contractors to take on security jobs in war zones.

While these security firms continue to play a key role in securing Iraqi facilities, the number of US contractors in Iraq decreased from 150,000 in 2008 to 66,000 in 2014. Although the Olive Group already has established its presence in Iraq (securing Najaf International Airport and oil fields in the south), the new role it is about to assume will have long-term implications for Iraq and its neighbors.

Further, President Donald Trump’s Administration apparently helped broker the highway deal. There are reports that an aide to Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi said that Trump’s son-in-law and senior advisor, Jared Kushner, raised the issue during his visit to Baghdad in April. While the parameters of the deal are neither clear nor published, the 25-year contract includes securing and maintaining the road, repairing the damaged bridges, and building rest areas. The US firm is expected to collect tolls from passing trucks and pay taxes to the Iraqi government in return.

Anbar, which constitutes one third of Iraq’s overall area, is a key province with access to Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia. The Anbar council looks at the Olive Group project as a major economic and political investment that will help secure their area, generate jobs, and transfer a portion of the revenues from the central government. The tribal fighters in Anbar, who constitute a Sunni version of the PMF, are around 17,000 and the provincial council hopes 5,000 of them will be recruited as security guards in the new project.

The advocates of contracting the Olive Group argue that it saves a lot of money for the Iraqi economy, which is drained by a budget deficit, and that Iraq has little experience in maintaining highways (Highway 1 was built in the 1980s). The offer was attractive to the Iraqi government since it does not have to pay cash up front. However, critics of the deal seem to have objections about the identity of the firm. There are two recurring criticisms: first, the fact that a US security firm will now have control of all the border crossing data of Turaibil such as fees and traffic volume, and second, the Olive Group’s ties with the ill-reputed Blackwater.

After speaking for weeks about how the US firm will secure the highway, Abadi recently fell silent on the issue. He had to make some concessions as political pressure was increasing. Iraq’s national security advisor, Faleh al-Fayyad, acknowledged1 in August that the Abadi government sanctioned security measures by the PMF to protect areas along the Baghdad-Amman highway from IS attacks. A 300-kilometer earth barrier was built, separating western Anbar (where IS remains active) from central Euphrates (the provinces of Najaf, Karbala, Diwaniya, Babel, and al-Muthanna).

While the Olive Group should have begun its operations officially in July, there are no indications that the contract was cancelled. A few obstacles remain. First, the US firm wants Iraqi forces to complete all operations in western Anbar because the Iraqi security guards that Olive Group will recruit will not be expected to serve in a combative mode. Second, Abadi might need some time to shepherd the arrangement through Iraqi politics. Third, a few pending details are yet to be finalized on the jurisdiction of the Olive Group and its interaction with Baghdad and the Anbar Province council.

Strategic Implications: US and Iran Competition

The significance of controlling the Baghdad-Amman highway cannot be overstated. The roadway that goes into Syria, via the al-Waleed crossing, leads to the al-Tanf military base where US forces are currently based. Along that highway in Anbar Province, US forces are also deployed in al-Habbaniyah military base (between Fallujah and Ramadi) and in Ain al-Assad air base in al-Baghdadi. US officials believe that the contract with the Olive Group will serve two purposes: to help the economic development of Anbar and to push back Iranian-backed PMF groups.

Furthermore, in southwest Anbar, another roadway splits from Highway 1 to the Arar border crossing toward Saudi Arabia. That border was reopened last month after 27 years of closure, which is part of a diplomatic effort to reassert US and Arab influence in Iraq to counterbalance Iranian leverage. The project around Highway 1 could ultimately build a Sunni buffer zone that would ease Saudi and Jordanian concerns about Iranian-backed PMF groups potentially deploying close to border areas in Anbar.

It is yet to be seen how effective securing the Baghdad-Amman highway can be. These efforts are tied to the larger context of US-Russian coordination in Syria. Iraqi forces cleared the road between al-Ratba and al-Waleed, which is a priority for US forces based in al-Tanf. However, the Baghdad-Amman highway cannot be fully secured without capturing the areas in the upper Euphrates that remain under IS control, most notably Rawah and al-Qa’im. Two key roadways also present decisive factors in that regard: 1) Road 20 between al-Ratba and al-Qa’im, and 2) Road 12 between al-Qa’im and al-Hasaka in northeastern Syria, which passes the al-Boukamal crossing into key towns in Deir Ezzor.

PMF groups that are close to the Iranian regime have publicly spoken against awarding the contract to a US security firm. Qais al-Khazali, the leader of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, said2 last April that the Iraqi government’s decision “should not go unnoticed and we have to stand against it.” These armed groups already connected with Syrian regime troops on the border in Umm Jurays, west of Sinjar, and they had aimed for months to head south toward al-Qa’im. However, IS attacks as well as lack of air support have prevented them from advancing. It is yet to be seen if the Iranian-backed PMF will advance south and challenge US forces.

Meanwhile, Iraqi forces, Anbar tribal fighters, and PMF members loyal to Abadi are slowly advancing toward al-Qa’im. US military leaders met earlier in September with Iraqi military commanders and Sunni tribal leaders to discuss plans to liberate Rawa and al-Qa’im from IS. On the Syrian side of the border, the regime and its allies are better positioned to seize control of the al-Boukamal border crossing with Iraq. At the same time, Iran remains focused on its supply line into the Levant. With Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) running the Yarabiya crossing and the US security firm in Turaibil, the only border crossing with Syria left to control is al-Qa’im. Hence, stakes are high for Tehran, whether in capturing al-Qa’im or resisting ongoing US efforts to control Turaibil.

Challenges Ahead and US Options

Beyond the security dimension, reopening the Baghdad-Amman highway is welcome news for the dire state of the economy in both Iraq and Jordan. During the closure of Turaibil, Jordanian and Iraqi commerce faced longer routes for trade activities, either by ground transport via Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, or by sea from Aqaba port, transiting in Jabal Ali port in the United Arab Emirates before reaching Umm Qasr port in Basra. Reopening the highway might also renew the talks about an oil pipeline project running from Basra to Aqaba. Before IS took over the border crossing, trade between the two countries had dropped from $1.29 billion in 2014 to $498 million in 2016. It is important to note that economic benefits will be delayed until the Baghdad-Amman highway is fully secure and functional, the upper Euphrates is liberated from IS, and an Iraqi consensus is reached on expectations from the US security firm.

The Iraqi central government, which lacks the resources to compensate the locals in Anbar Province who suffered under IS rule, looks at the highway project as an excuse to evade these financial burdens. However, this should not be a pretext for the Iraqi government to forsake its responsibilities and further alienate these areas along sectarian lines. Most importantly, the Iraqi government has been vague on where it stands on securing the Baghdad-Amman highway. Clarity on this issue and full transparency on the contract with the Olive Group are crucial steps to avoid political and security tensions down the road. The United States should encourage the Iraqi government to move in that direction.

Iraq is at a crossroads in the coming months. The post-IS period might witness the emergence of an emboldened Anbar Province that looks for more autonomy and relies on trade with Jordan and Saudi Arabia. As Kurdistan is striving for independence and the PMF is resisting calls to disband once IS is defeated, the fear is that the Sunni tribal fighters along the Baghdad-Amman highway might gradually become a force parallel to the Iranian-backed PMF. The Trump Administration must keep the Olive Group in check and acknowledge that protecting the US security firm in Anbar requires both a security and political context, whether inside Iraq or with its neighbors. Washington must also ensure that the Iraqi government is inclusive and has authority over its border crossings, trade routes, and military deployment as well as exclusive monopoly over the legitimate use of force. Deterring Iranian influence should not override the long-term goal of a viable Iraqi state.