Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif telegraphed his resignation on Instagram on February 25, apparently because he was not invited to meetings in Tehran between Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, President Hassan Rouhani, and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Two days later, however, Rouhani insisted that “it is in the national interest” that Zarif remain in office. Even Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Commander Qassem Soleimani claimed that Zarif’s exclusion from the Assad meetings had been a “bureaucratic” error and that he was in charge of Tehran’s foreign policy.

To fully grasp their wider meaning, these events must be viewed through the kaleidoscope of Iran’s factionalized political system. This is not a simple battle between Iranian hard-liners and reformists. Each of the broad factions includes militants as well as more conciliatory leaders who espouse a range of views on domestic and foreign policies. In a complex system whose stability requires containing conflict among multiple factions, Zarif is pushing for foreign consensus over confrontation. This requires a division of labor whereby the IRGC sustains its preeminent role in addressing regional security threats while Zarif and his allies in the foreign ministry and the reformist camp struggle against considerable odds to pursue constructive engagement abroad and, at home, a policy of economic reforms and very guarded political changes.

In a complex system whose stability requires containing conflict among multiple factions, Zarif is pushing for foreign consensus over confrontation.

Not surprisingly, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo dismissed these factional struggles as mere theater. Zarif and Rouhani, he tweeted, are only “front men for a corrupt religious mafia.” But Western European leaders do not share this view. Indeed, they have probably breathed a sigh of relief with Zarif remaining at his post. They can now finalize business plans for a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) to sustain Iranian oil sales and skirt American sanctions, thus countering internal pressures to renounce the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Moreover, unlike Pompeo, they believe that Zarif’s efforts to sustain the nuclear agreement provide an important domestic shield for the reformist camp whose survival depends, in part, on sustaining the foreign minister’s engagement strategy.

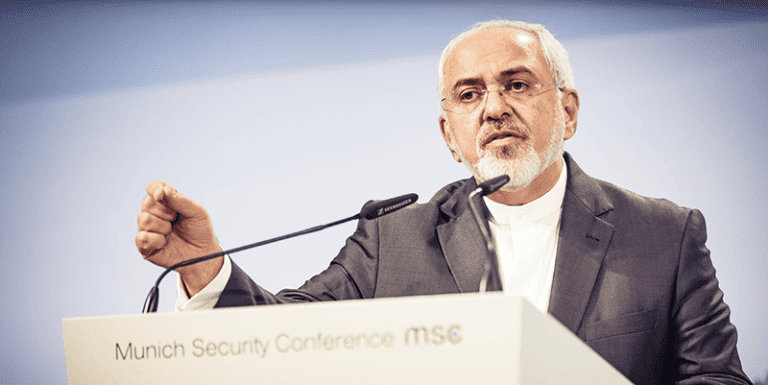

Still, the foreign policy division of labor between Zarif and the IRGC is hardly balanced. In addition to commanding the IRGC, Soleimani also chairs the Supreme National Security Council; he enjoys a level of trust with Khamenei that Zarif will never have. Moreover, Zarif faces an uphill battle when it comes to saving the JCPOA, but he also has some advantages. On the home front, he has support from both the leader and from many (but not all) reformists. On the international front, a fragmenting global order (which was on full display during the February 15-17 Munich Security Conference) could offer Zarif a chance to advance a wider dialogue on Iranian-European cooperation—provided that the warring parties in Syria, where Iran has been active for years, avoid the dangers of military escalation.

Diplomacy Versus Resistance

One day before he resigned, Zarif took a dig at his hard-line rivals, insisting that “we cannot hide behind imperialism’s plot and blame them for our own incapability. Independence does not mean isolation from the world.” Some of Iran’s hard-liners returned the favor, insisting to Zarif, as one put it, to “shut the door behind you.”1 If it turned out that Zarif opened rather than closed a door, this was not purely an exercise in personal pique. He is a committed Iranian nationalist and hard-nosed foreign policy realist who—to echo former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger—considers Iran a state as much if not more than a cause. Rouhani’s 2013 election gave Zarif an opening to advance this agenda. In contrast to the hard-liners’ pledge of resistance to the West, Zarif tried to make Iran a significant and acceptable player rather than merely the perennial bad guy in the global arena.

Rouhani’s 2013 election gave Zarif an opening to advance this agenda. In contrast to the hard-liners’ pledge of resistance to the West, Zarif tried to make Iran a significant and acceptable player rather than merely the perennial bad guy in the global arena.

The conventional wisdom in the Washington-centered blogosphere is that President Donald Trump’s decision to abandon the JCPOA pulled the rug out from under Zarif. But the rug had been slipping for some time. From the outset of Rouhani’s presidency, hard-liners feared that his engagement strategy would enhance the reformists’ domestic leverage. Their growing criticism of him, especially after the July 2015 signing of the JCPOA, was aimed in part at blocking any domestic reform strategy, especially one that included an even modest political opening. The pivotal military role that the IRGC played in Tehran’s efforts to back Bashar al-Assad and confront the Islamic State (IS) enhanced the hard-liners’ leverage, thus dramatically reducing the influence of Zarif and his foreign ministry. Trump’s repudiation of the JCPOA surely played into the hands of the hard-liners. But Khamenei backed Zarif’s efforts to work with the European Union (EU) in creating the aforementioned SPV to circumvent US sanctions.

Thus, a lopsided division of foreign policy labor emerged: Rouhani got the unenviable task of saving the nuclear agreement and defending a struggling engagement strategy while the IRGC expanded its control over regional security policy. This arrangement increased the chances that if Zarif failed to save the JCPOA, the IRGC would be well positioned to join forces with Khamenei in a final victory that would probably leave Zarif and his reformist allies out in the cold.

Are All Hard-liners Ready for the Costs of Victory?

Zarif and his sometime rivals in the IRGC have at least two reasons to avoid a head-on collision that might lead to his permanent departure from the foreign ministry.

First, the IRGC’s sole grip on security policy will be no blessing. If an actual Iran-Israel war erupts in Syria, for instance, the guards will be thrust into a conflict that could exact untold human, economic, and diplomatic costs, including a fracturing of Iran’s emerging entente with Russia and Turkey and a lost opportunity to forge a deeper connection with the EU. The collapse of the JCPOA will also confront hard-liners with reconstituting the nuclear program at the stage it had reached before the accord was signed in July 2015. At that point, Iran’s advanced centrifuges had the capacity to produce enough enriched uranium for one bomb, in just a few short months. But Tehran was far from creating a full-fledged nuclear weapons program that could exercise deterrence via the threat of a second strike. Since any move to create such a deterrent force might invite a massive US or Israeli attack, Iran used the diplomatic leverage it had gained from this revved up but still limited enrichment program to secure a deal whereby Tehran vastly reduced its nuclear program in return for ending sanctions. Because the 2015 JCPOA saved Iran from a far more menacing path, even if the agreement collapses, IRGC leaders might conclude that consolidating their regional gains is a better option than trying to go down that menacing road once again.

Second, while the IRGC enjoys an unrivaled partnership with the supreme leader, both must tread carefully. Iran’s system pivots around a complex balancing act whereby the competing interests of various factions and their constituencies are channeled and contained through elected and non-elected institutions whose ultimate arbiter is Khamenei. Banishing rival factions could leave hard-liners and the leader locked in a political embrace while the rest of society watches an increasingly empty dance floor. Indeed, given the street protests that have erupted over the last year—and against a backdrop of dramatic terrorist attacks undertaken by Sunni militant groups that appear to be supported by IS—the regime is now confronting a nation dangerously fragmented by social, political, and geographical divisions. To meet these threats, the supreme leader and the IRGC both need allies. Khamenei has surely anticipated the successful struggle that is not far off, and he needs to show that his office remains the preeminent arbiter of rival factions. He cannot play this role if hard-liners once again try to banish all rival factions. As for the IRGC, the logic of partial inclusion does not necessarily clash with its special relationship with the leader. Some cooperation with elected leaders—those who speak for Iran’s vast professional middle class—is necessary for containing elite conflicts and avoiding the dangers of a wider splintering of the political and social arena.

The supreme leader and the IRGC both need allies. Khamenei has surely anticipated the successful struggle that is not far off, and he needs to show that his office remains the preeminent arbiter of rival factions.

Ultra-Hard-liners Inadvertently Create an Opening for Zarif

The ultimate beneficiaries of such a crisis will be ultra-hard-line forces, i.e. those who advocate silencing every vestige of political and ideological pluralism from the system. While Zarif is no advocate of regime change, his most zealous adversaries believe—with considerable justification—that his advocacy of constructive engagement is part and parcel of a wider and potentially troublesome political project, every element of which must be defeated. Toward this end, over the last year they have launched a campaign to silence their supposed enemies.

The principal source of attacks against Zarif came not from the IRGC but rather from the Endurance Front. Led by Ayatollah Mohammad Taqi Mesbah Yazdi, this faction rejects engagement (even with Russia or China). Over the last year it has called not only for abandoning the JCPOA, but also for impeaching Rouhani, Zarif, and Majlis Speaker Ali Larijani, a veteran conservative who is no friend of the reformists. Indeed, the Endurance Front’s allies reportedly went so far as to physically threaten regime advocates for “negotiation.” Responding to these escalating attacks, Khamenei stated that those who were calling for Rouhani’s removal were “playing a role in the enemy’s plan,” thus underscoring the domestic hazards of unbounded factional warfare.

Zarif’s threatened resignation echoed, and was in keeping with, this warning. He not only denounced his rivals’ efforts to advance their absolutist domestic agenda by manipulating foreign policy debates, but he also taunted them for holding that the struggle against imperialism requires “isolation from the world.” Carefully laying down the gauntlet, he made it clear that he would continue to advocate for engagement and, in so doing, defend the place and legitimacy of Iran’s foreign ministry in the wider domestic arena. Rouhani’s ensuing call for Zarif to remain in office was clearly worded to emphasize that this demand came directly from Khamenei. That the IRGC’s Soleimani quickly fell in line is no surprise. Whatever his reservations about Zarif and the world view he champions, the IRGC commander (along with Rouhani) telegraphed that Khamenei remains the ultimate arbiter of the system.

Zarif not only denounced his rivals’ efforts to advance their absolutist domestic agenda by manipulating foreign policy debates, but he also taunted them for holding that the struggle against imperialism requires “isolation from the world.”

None of this will diminish the close alliance between the IRGC and the supreme leader. But with Zarif (and Rouhani) remaining in place, reformists may now have space to push back against the efforts of hard-liners to silence or intimidate advocates of domestic political détente and external engagement. Indeed, they apparently signaled as much when 160 members of the Majlis penned a letter asking Zarif to remain in place. Despite the divisions in their own ranks—and the determination of their rivals to silence them—this action suggests that many reformists see Zarif’s efforts on the global stage as playing an important role in their political future.

Zarif and Iran’s Regional Priorities

Zarif will be operating in a fluid diplomatic arena that could offer him advantages. Quite apart from the abiding anger among Western European leaders with Trump’s decision to abandon the JCPOA, these dispirited leaders have repeatedly articulated a growing and more fundamental angst about the very future of the global system. Whether, as the Brookings Institution’s Thomas Wright has argued, the Munich Security Conference actually marked the end of the “transatlantic charade,” there is little doubt that the meeting pointed to what could be a widening or even permanent breach between the United States and Western Europe. Under this darkening cloud, the ongoing Iran-EU discussions over creating an alternative to the US-dominated dollar trading system could take on wider diplomatic significance—perhaps even inviting what one Iranian writer calls a “new narrative for Iranian foreign policy.”

Quite apart from the abiding anger among Western European leaders with Trump’s decision to abandon the JCPOA, these dispirited leaders have repeatedly articulated a growing and more fundamental angst about the very future of the global system.

Rouhani himself may have signaled the wider import of Iran’s talks with Europe when he argued before the UN General Assembly in September 2018 that Trump’s abandonment of the JCPOA left Iran and the rest of the international community with the task of defending the principle of respecting international agreements. However self-serving, this position could suggest opportunities for Iran to position itself as a constructive part of an expanding debate about how to manage the challenges of an increasingly precarious multipolar world. Zarif’s bid to secure for Iran—and his foreign ministry—a voice in this debate faces challenges not only at home, but also in Iran’s regional backyard. Indeed, Zarif’s exclusion from the Rouhani-Khamenei meetings with Assad on February 25 underscores the larger stakes at play in Iran’s Syria diplomacy.

Zarif may have been trying to make this very point when he decried his exclusion from that meeting. Reports suggest that the discussion focused on how to manage the sometimes-tense entente between Iran, Syria, Russia, and Turkey. Ankara’s push for a “safe zone” along its southeast border could be a red flag for Iran, a point that Khamenei seemed to signal when he denounced the idea as a “plot” that had to be “firmly rejected and opposed.”

To be sure, the fact that Zarif was not asked to weigh in on this strategic discussion is telling. Given the IRGC’s control over Iran’s Syria policy, and Russia’s success in dominating the diplomatic discussions over Syria’s political future, Zarif will not have an easy time leveraging the diplomatic advantages that might otherwise accrue to Iran from a changing and contested global order. First and foremost, he and Rouhani must hope that the situation in Syria does not escalate into a full-fledged Iranian-Israeli war. If this happens, Zarif’s efforts to sustain a wider engagement strategy could go up in smoke.

1 Tweet is in Persian.

* Photo credit: Munich Security Conference.