There have been recent reports of continuing negotiations between Palestinian factions in the Gaza Strip and Israel through third-party mediators, including the United Nations and Egypt. Even Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu is reported to have made a secret trip to Egypt for discussions on these negotiations. Simultaneously, however, several episodes of Israeli bombardment indicate that Israel might again choose to advance to a full scale war against the besieged strip. This war may even lead to reoccupying Gaza, an idea considered “absurd” by some Israeli security experts but still advocated as a serious option by others. Questions thus arise about why such negotiations are taking place now and whether they are part of a larger plan of action involving a longer-term peace deal centered around Gaza instead of the West Bank.

The Context of Trump’s “Deal of the Century”

Since taking office in January of 2017, the Trump Administration has talked about Israeli-Palestinian peacemaking and its efforts have been led by a troika of Trump confidants: his son-in-law, Jared Kushner; bankruptcy lawyer and settlement financier-turned-ambassador, David Friedman; and Trump organization legal officer-turned-special envoy, Jason Greenblatt. Despite the president’s confidence in team leader Jared Kushner, to whom President Trump said at an event right before his inauguration, “If you can’t produce peace in the Middle East, nobody can,” the team seems to have directed the situation further away from peace than ever before.

The embassy move was yet another reason for Palestinians not to participate in any peace negotiations led by the Trump Administration.

Early on, the Trump Administration did not take an overtly adversarial position toward Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman Mahmoud Abbas. But the White House’s embrace of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and its failure to clearly state that it backed a Palestinian state left an already demurred Abbas even more reticent. Then, new forms of pressure began with the aim of coercing the Palestinian leader to accommodate the administration’s objectives. Bills in Congress that would limit aid to the Palestinian Authority (PA) moved forward and Trump himself began threatening to move the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

When these tactics did not work, the Trump team used its relations with key Arab players in the hopes of sending a message to Abbas that he either complies with Washington or gets left behind—but this failed as well. Then the administration pulled the trigger and moved the US embassy, thus recognizing Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. This turned out to be the disaster it was predicted to be. The smiling faces of Trump envoys alongside Israeli officials at the embassy dedication in Jerusalem were juxtaposed across the world with images of the carnage Israeli military snipers wrought on protesters in Gaza. Both the Arab League and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation quickly slammed the move. Saudi Arabia, among the Trump Administration’s closest Arab partners in the region, also rejected it.

The embassy move was seen as an attack on Palestinians and yet another reason, added to a long list of reasons, for them not to participate in any peace negotiations led by the Trump Administration. The outrage in the Arab and Muslim worlds, and the positions Arab and Muslim governments took against the incendiary move, meant that the leverage Washington had built among some Arab states to use against Abbas had diminished. The embassy move may have shut the window for the American power play, at least for now. If direct pressure on the PA did not work and Arab states leverage had limited impact, what could Kushner and company use to press Abbas?

It soon became clear that the US embassy move dealt a blow to the previous strategy. Reports emerged that the United States was going to pivot in another direction: a “Gaza first” approach. Couched in language about humanitarian assistance and improving living conditions, both desperately needed in Gaza, the real aim of this approach is to pressure Abbas by appearing to boost his political rivals in Gaza. It was also supported by a reality that the status quo in the strip was simply not working. Israel’s policies of economic siege in Gaza, ostensibly aimed at weakening Hamas so that it could be dislodged from power, have created a humanitarian catastrophe—while leaving Hamas in place. It is noteworthy that this pivot to Gaza was also coming amid some of the most violent Israeli repression in Gaza in months, with weekly protests at the fence near the armistice line being violently put down by Israeli military snipers executing orders to keep the uprisings contained to the Gaza Strip.

The real aim of a “Gaza First” approach is to pressure Abbas to make more concessions.

Some Palestinians in Gaza, however, began to find ways to send messages across the fence for which the Israeli military had no answers. This included burning tires that sent billowing smoke into the air as well as launching incendiary kites and balloons that could burn fields where they landed across the fence. Israeli military and technological superiority proved ineffective against these most primitive of weapons and Israeli farmers adjacent to Gaza began to feel the impact in lost crops and burnt fields. This prompted the Israeli government to begin using military power against kites and balloons and targeting infrastructure in Gaza as a response, once again pushing the situation toward greater confrontation. If a “Gaza first” strategy is to proceed, even if only for the purpose of leveraging Abbas, it would first require some sort of resolution to the current confrontations.

A History of Negotiating with Hamas

Despite often saying it refuses to negotiate with Hamas, Israel has quite a lengthy track record of doing so, albeit through third parties. In various instances, agreements between Israel and Hamas have been negotiated and have partially held for periods of time. Most of these were cease-fire accords aimed at halting projectile fire from the Gaza Strip. It should be noted that Israel’s military options in stopping projectile fire are limited. Even when Israeli soldiers were stationed on the ground in Gaza prior to the 2005 removal of settlers from the enclave, Israel was incapable of eliminating it. That was also true when the Fatah-run Palestinian Authority was engaged in security coordination with Israel throughout the rest of Gaza. From outside the Hamas-controlled Gaza Strip, Israel has deployed shields. It has also tried both preemptive and punitive strikes, but at best, this is management of a problem and not a solution to it. Even after intense bombardment for weeks, Hamas has shown the capability to launch projectiles on the last days of such wars. Only through agreements have such weapons been brought to a near halt.

One such arrangement was in 2008 when Israel and Hamas agreed, through Egyptian mediation, that shelling from Gaza would cease if Israel would end extrajudicial assassinations there and ease the blockade. While Israel did not moderate the blockade, it did halt extrajudicial assassinations; firing from Gaza then dropped to near zero until the first week of November, when Israel killed several Palestinians. This attack effectively ended the cease-fire and led to a nearly three-week bombardment of Gaza, from late December 2008 to January 2009, killing some 1,400 Palestinians and destroying massive civilian infrastructure.

In 2011, Israel again negotiated with Hamas, through Egypt, for a prisoner release in exchange for one of its captured soldiers. Over 1,000 Palestinian prisoners would be released in exchange for Corporal Gilad Shalit, who was captured in a joint operation by the Popular Resistance Committees (PRC) and Hamas’s military wing in 2006. Leading the exchange from the Palestinian side was Ahmad Jabari, a leader of Hamas’s military wing. The exchange was made and the prisoners were released. Negotiations with Jabari proved fruitful; in the fall of 2012, the Israeli government was in the middle of negotiating a long-term truce with Hamas through Jabari when it decided instead to assassinate him. This sparked yet another conflagration, only to return to the status quo ante after the war was over.

Despite often saying it refuses to negotiate with Hamas, Israel has quite a lengthy track record of doing so.

Again in 2014, Israel’s heavy-handed tactics in the West Bank sparked new projectile fire from Gaza. In a massive operation after the death of three young Israelis at the hands of Palestinians, Israel arrested hundreds of people in punitive dragnets that included many of the prisoners released in the 2011 prisoner exchange. While the PRC responded with rocket fire, Hamas stayed out of the fray until Israel began targeting its members, signaling escalation. A month and a half of Israeli bombardment and invasion followed, leaving over 2,200 Palestinians dead, most of them civilians, and some 73 Israelis killed (67 of whom were soldiers).

In all instances, cease-fire agreements were shattered because of two key issues. First, the precise terms of the agreements were never clarified publicly. Keeping the terms shrouded may have been attractive to both sides as this obscured the exact agreements and concessions by each side, allowing them to save face by telling their versions of the story to their own domestic audiences. But this was a double-edged sword because the lack of transparency also meant there would be a lack of accountability for violations.

Second, there was no independent mechanism that could both monitor cease-fire violations and investigate and hold violators accountable. This meant that each party reserved the right to respond to violations. Without an agreement regarding what constituted a violation and no independent mechanism to mediate disputes, it would only be a matter of time before an exchange of fire would lead to another war.

Events in early August 2018 were a perfect example of how the absence of a verification and accountability mechanism for cease-fire enforcement could lead to the brink of war. Just as a high level delegation of Hamas leaders was preparing to head to Cairo as part of negotiations for a reported longer-term truce, the Israeli military launched an attack on a Hamas position killing two Palestinians inside Gaza. At first, the Israeli military claimed that the Palestinians fired first and it responded, only to admit later that it had not in fact been attacked. Nevertheless, this deadly Israeli attack led to Palestinian responses and further Israeli strikes that left several Palestinians dead, including a pregnant mother and her toddler, after Israel fired dozens of missiles and conducted airstrikes over a 72-hour period. Both parties took steps, albeit dramatically different in their scale, that had not been seen since 2014. Hamas launched a projectile that reached Beersheba, much farther from the immediate areas surrounding Gaza that are normally threatened by rocket attacks, thus reminding Israeli of its reach. The Israeli military also destroyed a multistory cultural center in the heart of a residential area in Gaza.

What’s Different This Time?

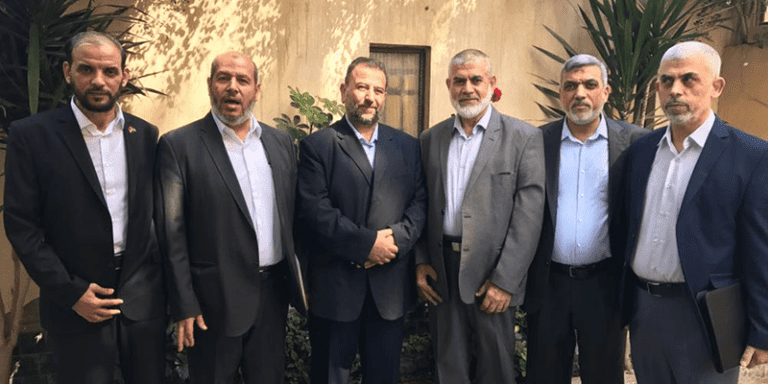

As Israel and Hamas move toward a possible long-term negotiated truce, once again mediated by third parties, circumstances today are different. Importantly, key Hamas figures are in Gaza whereas in previous years the head of the political leadership, then Khaled Meshaal, lived outside of it, which sometimes complicated negotiations. In 2017, Yahya Sinwar took over the political leadership of Gaza from Ismail Haniyeh, who in turn took over the Hamas politburo from Khaled Meshaal. Both men—Sinwar and Haniyeh—were based in Gaza.

What is also different about these most recent negotiations is that the Hamas delegation has included Saleh Arouri, a long-time member of Hamas from its founding days and its politburo deputy head. He has travelled around the region during the last decade after being expelled from Gaza and reportedly forced out of Damascus and later Turkey. Arouri is reportedly in charge of Hamas’s military operations in the West Bank; Israel charged him with responsibility for directing the abduction and murder of three Israelis in the summer of 2014. After a global Israeli campaign to marginalize him, he was placed in 2015 on the US Treasury Department’s terrorism financing list. .

Without an independent mechanism to enforce cease-fire terms, it is hard so see how any truce wouldn’t inevitably crumble.

Now, after being in Israel’s crosshairs, Arouri suddenly walked back into and out of Gaza for possibly the first time in eight years. His public participation in the delegation negotiating an Egypt-facilitated truce was no doubt greenlighted by the Israelis as well. All of this seems to suggest that the negotiations taking place around a longer-term Gaza truce might be more serious than previous attempts, or perhaps that they are intended to look that way for an audience of one sitting in Ramallah—i.e., PLO Chairman Mahmoud Abbas.

What will come of these talks, if anything, is yet to be seen. There have been reports that a long-term agreement could include not just a cease-fire and an easing of the blockade but also investment in Gaza and other arrangements aimed at serving the population there, including the development of a sea port and an airport possibly in Sinai. But even if this is included in the framework of an agreement at the outset, past experience shows that the challenge is getting the parties to honor the agreements. Without an independent mechanism entrusted by both sides to enforce cease-fire terms, it is hard so see how any truce agreement could stick without inevitably crumbling again.