According to the latest media reports, the Syrian regime may have succeeded in taking control of the Eastern Ghouta area adjacent to the city of Damascus. Thus, it now has authority over areas that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, in a previous statement, referred to as “useful Syria“—the western part of the country and location of most of its population and economic activity. But this success came at the expense of thousands of dead and wounded in the region and tens of thousands of displaced people, including those fleeing military operations. Meanwhile, numerous United Nations Security Council resolutions on the Syrian crisis remain a dead letter. International condemnations of the behavior of the regime and its supporters—including the Russians, Iranians, and militias from Lebanon and Iraq—have not hindered the Assad government’s quest to impose the final solution it wants on the ruins of the Syrian people, state, and economy.

The Situation in Eastern Ghouta

The Assad regime was able to take almost complete control over Eastern Ghouta, after it divided the Damascus suburb into three areas: Arbin, Harasta and Duma. Although the implementation of the agreement to evacuate fighters from Arbin and Harasta to Idlib began in March, Duma held out until early April, when the entire region fell under the regime’s control. This forced displacement, in the Syrian regime’s playbook, has become synonymous with the total uprooting and relocation of the civilian population to refugee and displacement camps in other cities. Although reports indicate that 40,000 inhabitants may have returned to the area, there is no specific overall plan for those who were displaced around the country to return to their homes and cities; and prospects are unclear for the future. For example, displaced inhabitants of Darayya, Zabadani, and Madaya––all areas close to Damascus––have not been able to return to these cities, and it has been several years since the Assad regime and allied militias took control of them.

In less than 45 days, more than 1,700 civilians lost their lives.

All of this points to a clear strategy on the part of the Assad regime to displace communities from all civilian areas that are out of its control, and without any plan or interest in the return of these civilians to their cities and homes. What is important is the physical control of these lands, regardless of military or civilian cost. The current military strategy seems no different from the previous plans for other cities. In Aleppo, which was subjugated by the regime in late 2016, hospitals and medical centers were heavily targeted to destroy any hope of life or healing for those who remained under siege. This was followed by intensified and indiscriminate air strikes against civilians and civilian installations, such as schools and kindergartens, and without respect for international humanitarian or human rights laws. Hence, it was impossible to continue living in what became a virtual hell, forcing all inhabitants to leave the area by any means and as soon as possible since they knew that staying meant certain death.

Preliminary data, in the absence of full accounting by international and human rights organizations, indicate that in less than 45 days, more than 1,700 civilians lost their lives during the recent Syrian-Russian military operation in Eastern Ghouta.

The Syrian regime’s forces completely denied access to humanitarian convoys. They permitted only individual trucks to enter in order to circumvent international resolutions accusing the regime of not allowing UN humanitarian convoys to enter Ghouta. The regime was aware that these individual trucks would not be able to provide aid to the more than 400,000 civilians who were living in Eastern Ghouta at that time. Hence, these inhabitants realized that they would not be allowed to live, despite enduring a punishing siege for the last five years. They had to make a final choice—between displacement and death.

In reality, no one expected a different stance from Russia or the Assad government. The war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the Syrian regime over the past seven years make it clear that the Syrian regime has no respect for the law, especially international humanitarian law. Thus, there was no doubt that it would do whatever was necessary to control the remaining areas outside its control in the vicinity of Damascus.

The Syrian regime may want to physically control all of the country, but potential escalation with Turkish and United States troops may curb its ambition.

What was most surprising for the Syrian people and observers alike was the lack of international accountability for what happened in Eastern Ghouta, despite several UN Security Council resolutions that obligated the Assad regime to respect cease-fires and allow humanitarian access to the region. They were especially surprised given the stand expressed by the US ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, who used very strong language and threatened to resort to measures outside the Security Council if the world body failed to guarantee the implementation of UNSC Resolution 2401 of February 24, 2018. This resolution “Demand[ed] that all parties [to Syria’s seven-year-long conflict] cease hostilities without delay, and engage immediately to ensure full and comprehensive implementation of this demand by all parties, for a durable humanitarian pause for at least 30 consecutive days throughout Syria, to enable the safe, unimpeded and sustained delivery of humanitarian aid and services and medical evacuations of the critically sick and wounded, in accordance with applicable international law.” But this resolution remained meaningless as air and field bombardments continued and Assad’s forces widened their control.

Scenarios for Syria’s Future

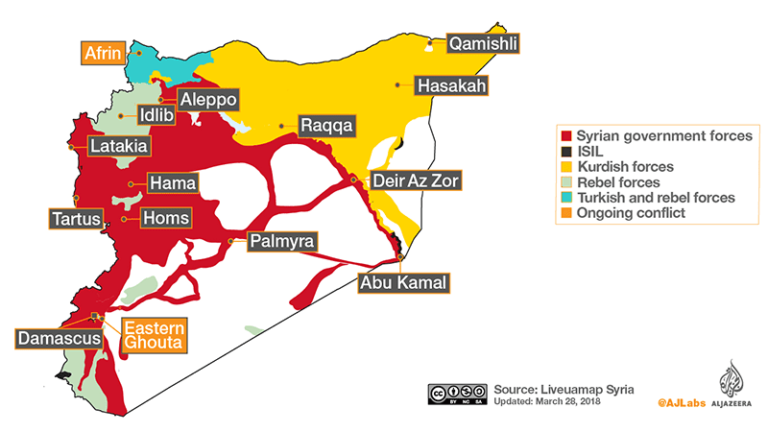

The scenarios for Syria’s future after the fall of Eastern Ghouta now look very different from those drawn in 2012 or 2013, which depicted a peaceful political transition from Assad’s rule. This change became especially apparent after direct Russian military intervention in September 2015 which played a decisive role in changing the balance of power in favor of the Syrian regime. The intervention allowed the regime to regain control over three strategic areas formerly controlled by the opposition, namely Homs, Aleppo, and Eastern Ghouta. Taking over these areas, with strong assistance from Iranian militias and Russian armed units changed the strategic landscape, especially after the defeat of the Islamic State (IS) in the north and northeast of Syria. IS areas are now controlled by the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) that are allied with the United States.

There are three possible scenarios for how things may turn out in Syria. These may also help in predicting the outlines of the country’s future.

Scenario 1. The Syrian regime could regain all areas currently outside its control, including Idlib and the Aleppo and Hama countryside which are still in the hands of the Syrian armed opposition (such as the Free Syrian Army that is partially supported by Turkey) and of the YPG (partially supported by the United States) which controls Raqqa, Ayn al-Arab (Kobane), and Qamishli. But to do this, the Assad regime, which is supported by Russian and Iranian forces, would almost certainly clash with Turkey and the United States.

The most likely scenario for Syria is that international and regional powers divide the country into areas of influence.

This scenario is thus unlikely to materialize in the near future, as Russia has no interest in direct military escalation with Turkey or the United States on Syrian soil, despite the Syrian regime’s repeated declarations about wanting to control all Syrian territories. Therefore, there would certainly be pockets outside the Syrian regime’s control which may be as large as whole cities or governorates, such as Raqqa, Idlib, and the Aleppo and Hama countryside. This scenario would be the dream scenario from the standpoint of the Syrian regime, but it is most unrealistic given the map of regional and international alliances concerning Syria today.

Scenario 2. This scenario entails the division of Syria based on areas of influence mentioned in the first scenario. The interior of the country would be under the control of the Syrian regime, sharing power with Russia in the coastal region and guaranteeing the continuation of Russian military bases in Humaymim and Tartous. Iran also would have a role to play in this “useful Syria.” Regime forces would be deployed in other areas such as Aleppo and Eastern Ghouta. Southern Syria would remain under the control of the Syrian armed opposition, based on the Jordanian-Russian-American understanding of non-escalation in that area, and the continuation of the frontlines as they were in 2014. The Syrian-Jordanian border crossings would remain closed or suspended.

As for northern Syria, which covers territory from Qamishli in the east to Idlib in the west, it would gradually turn from yellow (indicating areas under the control of the YPG) to green (areas under the control of the Syrian armed opposition). These forces succeeded in pushing YPG forces from Afrin and would be expected to do the same in Manbij. Additionally, according to Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkish forces are determined to expel YPG forces from all of northern Syria.

With regard to eastern Syria, the United States maintains strong influence, especially in Raqqa and its surrounding areas. Washington has announced, through statements made by Defense Secretary James Mattis and former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, that it will retain its military forces in Syria for quite some time to secure and achieve the political transition after Assad and to ensure that no extremist organizations benefit from the prevailing chaos in the country. Thus, eastern Syria will remain under American and YPG influence for a certain period; and it is noteworthy that the YPG’s clout in the Syrian north is shrinking due to Turkish expansion.

According to this scenario, international and regional powers would divide Syria into areas of influence that would shift according to evolving relations among them and changes in their interests and internal political considerations. No changes would be expected in how Russia and Iran see their role in Syria, but given the internal problems the Trump Administration faces, Washington’s stand there may see some alteration. President Donald Trump has in fact instructed military leaders to prepare for a pullout from Syria but has not decided the timing for it. Still, however, the Pentagon does not seem fully convinced, with the head of the US Central Command General Joseph Votel saying that “the hard part, I think, is in front of us.”

There could be multiple, new, and possible “Syrias,” or we might simply witness the unraveling of a failed state over a period of decades.

At present, this scenario seems to be the most probable for the future of Syria, with possible adjustments in areas of influence according to changes in the balance of power and relations between different actors. However, it is prone to fundamental changes if the United States chooses to withdraw completely from Syria, or if Turkey decides to extend its control over the territory under the control of the YPG in eastern Syria. Then again, there are the unknowns that may emerge from the Turkey-Russia-Iran meeting in Ankara that no one really knows how it will affect the final picture of this scenario.

Scenario 3. The third and final scenario is that of a failed state––ironically a prediction made by former UN Envoy to Syria Lakhdar Brahimi in 2014––that would be unable to protect its sovereignty, borders, or air space. It would also not be able to protect its citizens but seek to displace and expel them. This indeed is the case today, where the regime forces people to flee and most services provided by the state, such as electricity, water, and security, have been disrupted in most areas or are completely absent. All Syrian regions, whether under the control of the regime or the opposition, are dependent on international assistance and UN humanitarian programs. Thus, in one form or another, Syria has become subject to international tutelage—although the United Nations has not acknowledged it. In addition, the country’s air space is violated by all parties. In a one-month period in February, four planes belonging to four different nations—Russia, Iran, Israel, and Turkey—either crashed in Syria or were shot down after flying over Syrian territory, a situation attesting that the Syrian conflict has been “internationalized” and illustrating the complete and definitive collapse of Syrian sovereignty.

Syrian refugees and displaced persons are currently paying the cost of this scenario. In a way, the situation is an inevitable result of the struggle between the first and second potential scenarios and has led to the reality that no one can deny: that Syria as we know it no longer exists. A new Syria is being formed, but it is not yet born. There could be multiple, new, and possible “Syrias,” or we might simply witness the unraveling of a failed state over a period of decades, one resulting from the brutality of the regime and the indifference of the international community.