The first round of the US-Iraq Strategic Dialogue, conducted by video on June 11, yielded some important results the most impressive of which was the fact that the two sides were able to hold such a dialogue at all. Iraq has experienced six months of political chaos following massive anti-government street protests, the resignation of one prime minister, the tumultuous process of selecting another and forming a new government, the eruption of the coronavirus pandemic, and signs of an Islamic State (IS) resurgence. Galvanized, perhaps, by the numerous crises facing Iraq and the bilateral relationship, both governments were able to engage seriously on several critical issues, including the future of US forces in the country.

Broad agreement is one thing, but implementation another. The fledgling government of new Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, picked by the parliament in May, will be hard-pressed to implement agreements with Washington, especially those that might involve cracking down on the Iran-allied militias of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) or curbing the influence of Iran more generally. Much more discussion will be needed, and another round of the Strategic Dialogue is planned, potentially in Washington later this month.

Round One: Laying Down Security Markers

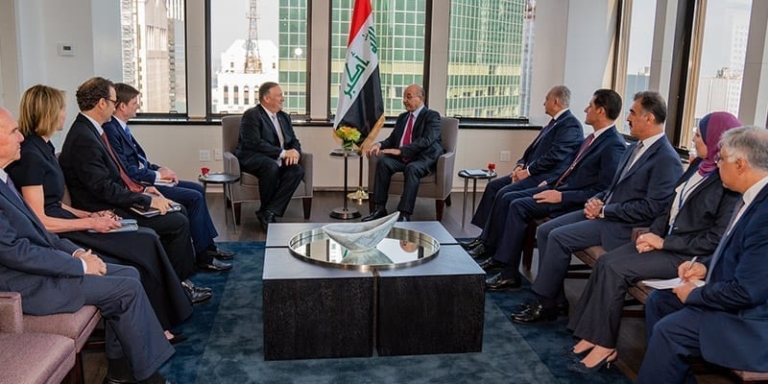

Considering the state of Iraqi politics and security, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo set a high bar for the talks when he announced them in April, noting that “all strategic issues between our two countries will be on the agenda, including the future presence of the United States forces in that country, and how best to support an independent and sovereign Iraq.” Pompeo stressed the dialogue was critical to “stop any reversal of the gains we’ve made in our efforts to defeat ISIS and stabilize the country.” This had emerged as a major worry after the global pandemic disrupted the battle in Iraq against the Islamic State.

The key point of agreement reached between the two sides in the first round of the dialogue concerned the future of the US military presence in Iraq, which has been a point of contention between Iraq and the United States for well over a decade. The Strategic Framework Agreement (SFA) signed between Baghdad and the George W. Bush Administration in 2008 called for the withdrawal of US forces by the end of 2011 unless a new bilateral agreement was reached on their status. The failure of negotiations on this point led to President Barack Obama’s decision to go ahead with the troop withdrawal. American forces were ramped up again at Iraq’s request in 2014 to assist in the fight against IS and approximately 5,000 US soldiers remain today.

The US-Iraq joint statement following the conclusion of this round of talks reaffirmed both the SFA and subsequent exchange of diplomatic notes that affirmed the legal legitimacy of the ongoing US presence in Iraq. Significantly, though, it also emphasized that the United States “does not seek nor request permanent bases or a permanent military presence in Iraq,” a key Iraqi priority, and pledged “its respect for Iraq’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, and relevant decisions of the Iraqi legislative and executive authorities.” This was an acknowledgment of the sentiment—and votes—in the Council of Representatives (COR), Iraq’s parliament, in favor of the complete withdrawal of US troops. The United States also promised to “continue reducing forces from Iraq,” another concession to opposition views.

Iraq committed to preventing or punishing attacks on US and coalition facilities and forces, a growing problem that forced the United States to stand down from operations against IS in January and consolidate its force presence to fewer bases.

For its part, Iraq made an effort to address key US concerns by underscoring that it would “[protect] the military personnel of the International Coalition and the Iraqi facilities hosting them consistent with international law and the specific arrangements for their presence,” to be clarified in further talks. In other words, Iraq committed to preventing or punishing attacks on US and coalition facilities and forces, a growing problem that forced the United States to stand down from operations against IS in January and consolidate its force presence to fewer bases. (These attacks were also a proximate cause of the US drone strike in early January that killed Iranian Quds Force Commander General Qassem Soleimani, along with Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, a top PMF leader. The slaying was recently termed “unlawful” by UN Special Rapporteur Agnes Callamard.)

Initial indications suggest that Kadhimi, a former intelligence chief with close ties to Washington, is taking the obligation seriously. In late June, the prime minister branded militias that attacked Iraqi bases and airports—where many of the American troops are based—as “outlaws” and “terrorists.” In a major act of enforcement, on June 25 the US-trained Counter Terrorism Service (CTS) launched a raid on militants from Kataeb Hezbollah, a leading PMF element, as they were preparing an attack on Baghdad’s Green Zone, possibly including the US embassy. The move was consonant not only with Iraqi pledges to the United States but with Kadhimi’s long-standing desire to assert authority over the militias in the name of putting Iraqi sovereignty on firmer footing. Naturally, some PMF leaders denounced the raid as “treason,” one intended to please the United States, thus upping the political pressure on Kadhimi to back off. Indeed, 14 Kataeb Hezbollah militiamen arrested in the June 25 raid were released three days later after armed threats to CTS headquarters by the militia forces.

Whether Kadhimi has the political clout to prosecute his campaign against the militias remains to be seen. His evident determination, though, is likely to be enough on its own to mollify the United States for now and lay at least partial groundwork for a productive second round of the Strategic Dialogue. The forces arrayed against him are considerable, however. They include Iran, which has worked to paint Kadhimi’s anti-PMF actions as doing America’s bidding, and a number of the militias themselves that are believed responsible for the assassination of pro-Kadhimi military analyst and government advisor, Hisham al-Hashimi, in Baghdad on July 6. The murder seems intended as a warning to the prime minister.

Whether Kadhimi has the political clout to prosecute his campaign against the militias remains to be seen. His evident determination, though, is likely to be enough on its own to mollify the United States for now.

The first round of the Strategic Dialogue, held by videoconference due to the coronavirus pandemic, was necessarily truncated in form and substance, leaving a great deal to further discussion. In addition to security questions, the talks touched on humanitarian, cultural, and economic issues, including Iraq’s rebuilding needs, and the importance of assisting Iraq in carrying out free and fair elections. But there remains a great deal of work to be done and considerable details to be filled in, amplifying the importance of the second round.

Round Two: Devil Is in the Details

Tentatively planned for this month, and possibly involving a yet-to-be-scheduled visit to Washington by Prime Minister Kadhimi, this stage of the dialogue is likely to focus on filling in the blanks on the status of US forces and Iraqi commitments to protecting them.

The United States will probably demand more detail and broader commitment from the Iraqi side vis-à-vis security pledges made in June. These might include specific demands for action against individual militias and militia leaders. In addition, the United States is likely to press the Iraqis to take strong action to make sure that the PMF, nominally part of the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) structure, strictly obeys the chain of command and all lawful orders of ISF commanders.

The United States will also be interested in performance benchmarks by which to measure the Iraqi commitment to sustained effort to rein in militia forces, including observed implementation of force protection measures as well as persistent legal pressure on militia members responsible for planning or executing attacks. The issue will remain crucial not only for the United States but also for the 1,200 troops of the 28 other nations still in Iraq under the umbrella of the US-led coalition.

The United States and Iraq must also focus on continued reform of the ISF, in addition to training and equipment needs, to maintain momentum against the Islamic State and ensure the ISF is capable of meeting any internal security challenge. One important component of this discussion must be human rights training for the security forces who (like certain PMF elements) have been credibly accused of numerous deaths of protesters in the demonstrations last fall and in the early part of this year.

The United States and Iraq must also focus on continued reform of the ISF, in addition to training and equipment needs, to maintain momentum against the Islamic State and ensure the ISF is capable of meeting any internal security challenge.

Progress along these lines will depend largely on whether Kadhimi can continue to build consensus within Iraq on his government’s legitimacy and on the efficacy of his job performance. Recent polling suggests he is on the right track; according to a new survey, 63 percent of Iraqis approve of the new prime minister’s first month in office. Views of Iran are changing, too: a mere 14 percent of those surveyed rated Iran as a reliable partner, compared to 74 percent in 2017. (It is noteworthy that favorable views of the United States have held steady, at around 30 percent.)

The sustainability of these favorable trends will be possible only with substantial outside assistance, and it is in this area that Baghdad is likely to press Washington for stronger and more specific commitments in the second round of the Strategic Dialogue. These may include specifics on how Washington will encourage the “world-class” American companies, mentioned in the June communiqué, to partner with Baghdad on development and reconstruction projects, as well as more detailed US technical and financial commitments to Iraq. The latter will prove especially difficult given the global economic crisis and the sharp downturn in the United States; however, US assistance is more critical than ever given the devastating financial crisis Iraq is now experiencing due to the oil price collapse. The United States is not inclined to provide substantial new infusions of cash, but it has indicated it would be amenable to helping through international financial institutions. In lieu of more financial aid, perhaps the best Iraq can expect is additional leniency on the application of US sanctions intended to force countries to break economic ties with Iran. This has been of particular concern to the Iraqi government due to its dependence on Iran for natural gas to power its electrical grid.

Two additional areas in which Iraq may focus requests for assistance are implementing efforts to reduce corruption and planning for the new national elections that must take place no later than two years from now.

With regard to corruption, this remains perhaps the most explosive issue of all, having hammered Iraq’s economic development and degraded government effectiveness, thus playing a major role in the massive anti-government demonstrations that began in late 2019. The United States has considerable experience as well as legal authorities and programs for combatting foreign corruption. It should be willing to utilize them in support of Kadhimi’s anti-corruption goals.

With regard to corruption, this remains perhaps the most explosive issue of all, having hammered Iraq’s economic development and degraded government effectiveness, thus playing a major role in the massive anti-government demonstrations that began in late 2019.

The Iraqi side should also press Washington about its plans to support “free and fair elections,” as promised in June’s joint statement. This could include technical expertise but also support for UN efforts to assist in organizing elections and, most important, to develop a new electoral law.

In seeking more US help, Kadhimi may even find support among some PMF elements. After Kadhimi’s selection as prime minister in May, Muhammed Al-Ghabban, leader of the Fatah parliamentary grouping of the PMF, indicated he was open to pragmatic relations with the United States. “Washington should demonstrate its interest in Iraq by giving priority to supporting Iraq at this critical stage,” he said, “and assure the Iraqi people of its seriousness in providing assistance to them, and not siding with any Iraqi political party against another.” Pro-Iran militias appeared to take a wait-and-see approach in the run-up to the talks and their immediate aftermath, tamping down their rhetoric.

This will not remain true as along as Kadhimi holds firm and attempts to keep the militias under control. Indeed, verbal attacks against him rose after the CTS raid on June 25. But counterpressure may be building: Ammar al-Hakim, leader of the Hikmah movement in the Council of Representatives, announced on June 30 that he is forming a new political bloc within the COR, called Iraqiyyun, aimed at supporting “the strong and capable state, with national sovereignty and public will”—an apparent bid to support Kadhimi’s agenda. It already commands 41 members in the 329-member COR, making it the fourth largest parliamentary bloc.

Thus, Kadhimi enters the second round of the US-Iraq Strategic Dialogue—whenever that takes place—in a relatively strong position domestically while his stock has risen in Washington. Given the magnitude of the challenges involved, however, it will take more than serendipity to transform the US-Iraq relationship into an instrument “to achieve security, stability, and prosperity in the region,” as the two countries envision.

The United States and Iraq Have Room to Maneuver

The Iraqi political landscape is more fluid than ever thanks to the coronavirus pandemic, government dysfunction, mass protests, and an economic collapse. This same fluidity, however, would seem to offer a major opportunity to reshape Iraq’s sectarian politics and its relations with the United States.

The Iraqi political landscape is more fluid than ever thanks to the coronavirus pandemic, government dysfunction, mass protests, and an economic collapse. This same fluidity, however, would seem to offer a major opportunity to reshape Iraq’s sectarian politics and its relations with the United States to put both on a more stable, productive footing. Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s capable early leadership and strong approval numbers enhance his prospects to drive Iraq in the right direction. In the meantime, Iran and its Iraqi allies have lost influence, as reflected not only in Tehran’s declining approval ratings but its increasingly dire economic straits brought about by lower demand for oil as well as harsh US sanctions. This is not only an opportunity for Kadhimi to push his sovereignty agenda by taking firmer control of the ISF and cracking down on illegal militia activity, but it is also an opening for the United States to push back against Iran’s regional influence by curbing Tehran’s ability to maneuver within the Iraqi political system.

Such moves would necessitate adroit American diplomacy, however, as well as sustained focus and aid resources (whether financial or programmatic), all of which appear to be in somewhat short supply as Washington faces its own roiling crises and the upcoming presidential election.

Even so, Washington could at least align its public and private diplomacy closely with Kadhimi’s mandate for his new government and “urge all political actors to come together around a national program to serve Iraq’s interests” and “not allow any country to violate Iraq’s national sovereignty.” Principally, this would require Washington to refrain from using Iraq as a pawn in its struggle with Tehran. If the administration could holistically support Kadhimi’s approach, it would do much to stabilize both Iraq and the US-Iraq bilateral relationship.