On August 13, President Donald Trump signed the “John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year [FY] 2019.” While the $717 billion defense budget does not necessarily dictate US policy in the Middle East, it reflects the areas of agreement between the White House, the Pentagon, and Congress. It abides by the congressional limitations on US policy unless new threats or opportunities emerge that require new approaches.

The FY 2019 budget provides insights on the transitional phase of the United States’ military doctrine and the funding priorities to meet next year’s immense challenges in the Middle East. It also reflects the increasingly dangerous regional environment Washington currently faces, especially after imposing fresh sanctions on Russia, Iran, and Turkey, all pivotal actors in the area. In general, the FY 2019 defense budget, which begins in October, puts Syria, Iraq, and Iran under one lump sum provision and ensures Israel’s qualitative military advantage in the region.

General Trends in the Defense Budget

The FY 2019 defense budget remains provisional, focusing on short-term investment in current military readiness and preparing for long-term future threats, as outlined by Defense Secretary James Mattis in a January 2017 memo. The FY 2020 budget, which the Trump Administration is expected to release in February 2019, will be shaped for the first time and until FY 2023 by the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS). This strategy shifts US military readiness from fighting terrorist groups to competing with what the NDS calls “revisionist” states (Russia and China) and “rogue regimes” (Iran and North Korea). The FY 2019 budget singled out China, Iran, and Russia as “potential adversaries” in cyber warfare.

There are clear congressional restrictions on long-term involvement and US military action in the Middle East.

While Trump has lauded the 2.3 percent increase in defense funding as “the most significant investment in our military and our warfighters in modern history,” this budget is consistent with the defense discretionary spending caps for FY 2019. It expands the active duty force by 15,600 (to become 487,500) with a cost of $139.3 billion along with a 2.5 percent military pay raise, the highest since 2010. After the dramatic increases in the defense budgets of 2018 and 2019, the Pentagon is not expecting “another big step up.” However, the Trump Administration will struggle in FY 2020 to find savings to meet these budgetary cuts and, for the first time, might have to reckon with allocating resources for the space force that could potentially become the sixth military branch, if approved by the Senate.

US military operations abroad continue to be funded under the “Overseas Contingency Operations” (OCO) that are meant to bypass discretionary defense spending, which stands at $616.9 billion as the base budget in FY 2019. The OCO funding peaked at $163 billion in FY 2010 and reached a low of $59 billion in FY 2016. However, it slightly passed $80 billion in each of 2017 and 2018, as the war on the so-called Islamic State (IS) intensified. The Pentagon forecasts that the OCO will stabilize at $20 billion in FY 2020-2023; hence funding for US military operations under OCO will significantly shrink in the next four years, which might explain why Trump is considering the option of having US contractors in Afghanistan. For FY 2019, OCO funding includes $46.3 billion in Afghanistan and $15.3 billion in Iraq and Syria. The United States currently deploys about 14,000 troops in Afghanistan and 3,765 soldiers in Iraq and 2,000 in Syria.

The defense budget, which was passed on schedule for the first time in 22 years, also strengthens US aerial and naval power by allocating, among other things, $7.6 billion to procure 77 of Lockheed Martin’s F-35 aircraft, $85 million for Sikorsky’s Black Hawk helicopters, and $24 billion for 13 new Navy warships, in addition to $197 million for cruise missile defense and $243 million to upgrade Stryker Combat vehicles to protect US soldiers in war zones from roadside blasts.

The Middle East in FY 2019

When it comes to the Middle East, there are two overarching themes and two priority countries in the defense budget, as follows.

Policy restrictions. There are clear congressional restrictions on long-term involvement and US military action in the Middle East. For the fourth year in a row, Congress asks the Pentagon for a detailed report to justify US support for the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and to show “demonstrable progress” benchmarks in retaking and stabilizing areas formerly held by IS. There are similar, though less restrictive, calls to explain the purpose of sustaining a US military presence in Iraq. The limitations imposed on the Kurdish Peshmerga forces in Iraq are far less than those on the SDF in Syria. The funding restrictions also hinder a long-term US plan in Syria. On August 17, the State Department terminated funding for Syria stabilization projects, citing increased financial contributions from regional partners. The FY 2019 budget clearly states that no provision “may be construed as authorizing the use of military force” against Iran or in Yemen.

The Trump Administration has not yet found a secure way out of Syria, one that would not damage the United States’ long-standing regional role.

Humanitarian concerns. The two main countries of humanitarian concern in the defense budget are Yemen and Syria. For Yemen, Congress calls on the defense secretary to review whether US forces interrogated Yemeni citizens in prison inside Yemen or provided questions for interrogation to any US coalition partner. It also asks the Pentagon to review whether coalition partners in Yemen “committed gross violations of internationally recognized human rights” during their operations, which might make them “ineligible for any training [and] equipment.” These concerns increase US pressure on Saudi Arabia to show restraint in its operations in Yemen. For Syria, the focus is on holding the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad accountable for “war crimes.” Congress asks the State Department for recommendations “on which transitional justice mechanisms” the US administration should support and allocates funding to train investigators within and outside Syria on how to document and investigate “alleged perpetrators of war crimes.” These provisions restrict any potential attempt by the Trump Administration to engage or recognize the Assad regime.

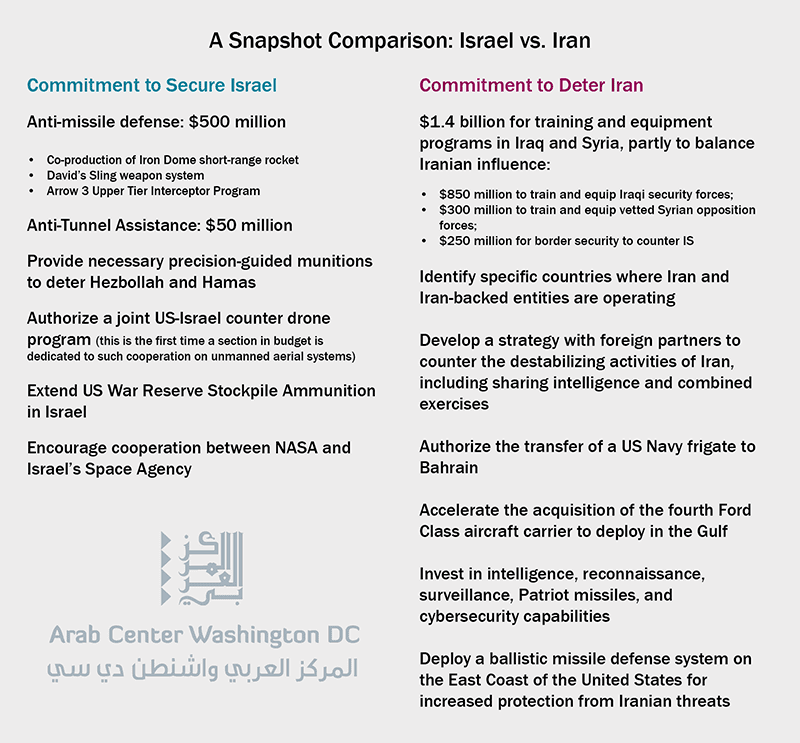

Securing Israel. The FY 2019 budget codifies the 10-year memorandum of understanding (MOU) that the Obama Administration signed with the Israeli government in September 2016. This MOU offered “the single largest pledge of military assistance in US history”—$38 billion over a decade. The language included in FY 2019 is unprecedented in its scope and content, lavishing US support on one single ally. The decision to help Israel with unmanned aerial systems came after Iran, Hezbollah, and IS flew drones in Syria during the past few years. This US support comes as the Israeli government seems increasingly concerned about the backlash of US-Iranian tensions and the potential for a growing number of heavy rockets and long-range missiles launched toward Israel. The FY 2019 budget urges the Trump Administration to begin talks with the Israeli government to determine “the quantity and type of precision guided munitions in the event of a sustained armed confrontation” with Hezbollah and Hamas.

Deterring Iran. The FY 2019 budget authorizes the Pentagon to create a strategy to counter Iran, which essentially calls for revitalizing US alliances, strengthening the US military posture in the region, and increasing pressure on Iran’s proxy network. The goal is to “enhance cooperation and encourage military-to-military engagement” between the United States and its partners “to counter the destabilizing actions of Iran.” However, Section 1295 in the FY 2019 budget immediately draws the line and affirms that this cooperation with allies does not mean, in any way, an authorization “to use force against Iran.” On August 22, White House National Security Advisor John Bolton conveyed the evolving US thinking on Syria, which is now linked to deterring Iran and not only combating IS. Washington also seeks to balance Iranian leverage by supporting the Iraqi and Lebanese armies, and the FY 2019 budget narrative warns about having any forces associated with Iran’s Revolutionary Guard infiltrate the Iraqi security forces and acquire US equipment and training.

The Defense Budget and the US Role in the Middle East

The FY 2019 NDAA tells us three things about the US role in the Middle East: 1) the Trump Administration has not yet found a secure way out of Syria, one that would not damage the United States’ long-standing regional role; 2) the administration has no clear way forward in dealing with Yemen and remains unable to balance between its commitment to support Saudi Arabia and increasing congressional pressure; and 3) the US commitment to Israel exceeds the US determination to deter Iran.

The expected significant decrease in US funding for operations in Iraq and Syria starting in FY 2020 casts a shadow on Washington’s ability to maintain leverage. As the war against IS winds down, the Trump Administration is weighing options for cutting expenses, such as reducing the number of American troops in the region. Reports from last February suggest that a slow withdrawal process of US forces in Iraq had begun while the commitment to keep US forces in Syria remains unclear in the medium term, given the ambivalent US approach.

If the United States is not willing to take the lead on deterring Iran, in resources and actions, allies will not follow suit or allocate significant funding.

Moreover, the shift of focus on Iran in FY 2019 does not match the Trump Administration’s rhetoric and stated policy objectives. Deterring Iranian influence in the two main war zones with Iran is restricted by congressional limitations. The Pentagon cannot earmark significant resources for Iraq and Syria and cannot give Saudi Arabia a blank check to defeat the Iran-backed Houthis in Yemen. The Trump Administration’s bet on having regional allies help deter Iran has proven ineffective. If the United States is not willing to take the lead on deterring Iran, in resources and actions, allies will not follow suit or allocate significant funding.

The defense budget also disregards the fact that the United States now has more foes and fewer allies in the Middle East because of the Trump Administration’s approach. The lack of international support for the renewed US sanctions on Iran and the emergence of a Russian-Turkish-Iranian alliance complicate Washington’s ability to confront Iran diplomatically. What masks this reluctance to deter Iran effectively is the unprecedented American support for Israel. Further, the FY 2019 defense budget entrusts the Pentagon to come up with an Iran strategy that seems no different from the current US approach to the Middle East.