In a three-hour long interview on July 12, Hezbollah’s secretary general, Hassan Nasrallah, addressed a wide range of local, regional, and international issues of concern to his party, Lebanon, and the region. The Shia militant group is largely known in American circles as contentious, to say the least; it is designated by the US government as a terrorist organization and often cast as an Iranian ally resisting American and Israeli policies. But in Lebanon––where Hezbollah and its allies have a majority of 72 members in the country’s 128-seat parliament and the party controls three ministries––it is above all a political actor, and often a pragmatic one. Hezbollah’s political and economic fortunes are inextricably intertwined with those of the rest of the country.

The Trump Administration’s sanctions against Iran, rapidly intensifying in recent months, have also taken aim at Hezbollah, most recently listing three senior members of the group on the US Department of Treasury’s sanctioned supporters of Iran. The action could not have been more symbolic of the twinning of the party with the whole of Lebanon. Two of the individuals listed, Mohammad Raad and Amin Sherri, are current members of parliament and, as such, are an integral part of the Lebanese political elite. Lebanon can no more solve any of its economic problems outside a dialogue with Hezbollah representatives than it can face down the group militarily.

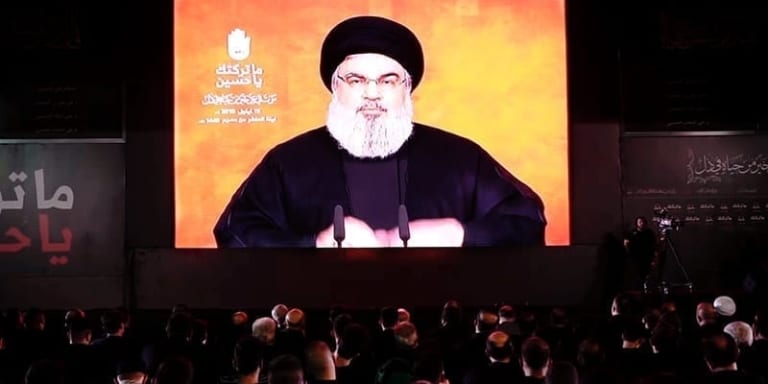

Nasrallah Responds

Typical of a sense of realism he has often demonstrated in tough times, Nasrallah admitted in the interview that Hezbollah was going through financial strains and, as a result, has implemented some painful austerity measures. In doing so, the secretary general was acknowledging the pinch that many in his party were no doubt experiencing. He was also responding to the commentaries, both sympathetic and antagonistic, which have appeared in the local and western media. Perhaps the most important message he wanted to deliver was that the party’s work goes on unimpeded and that anyone banking on challenging a weakened Hezbollah would be making a losing bet.

Hezbollah’s belt tightening measures, caused largely by a dip in Iranian largesse due to American sanctions on the Islamic Republic, are also part and parcel of Lebanon’s serious economic problems.

Hezbollah’s belt tightening measures, caused largely by a dip in Iranian largesse due to American sanctions on the Islamic Republic, are also part and parcel of Lebanon’s serious economic problems. They coincide with a planned austerity budget proposed by the Lebanese government, one that was hotly debated by parliament before finally passing with Hezbollah siding with the government against very loud protests inside and outside parliament by the opposition. While Hezbollah is trimming its budget by withdrawing fighters—who are no longer desperately needed—from Syria and cutting their salaries and subsidized services, the newly approved budget has controversially cut pensions for retired soldiers and salaries of public sector employees, such as those staffing the electric and Internet services for the country. During the budget debate, disgruntled employees demonstrated daily outside the parliament with scuffles and clashes breaking out between them and the military posted around Parliament Square.

Domestic Lebanese Politics

Since the murder of Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in 2005, Lebanon’s political elite has been split into a March 14 Alliance, led by the late prime minister’s son, Saad Hariri, and the March 8 Alliance, led by Hezbollah and allied parties. Though related to the bickering and polarization between these two groupings, Lebanon’s problems are more directly linked to the failure of the political elite to resolve fundamental structural problems of a faltering economy and a dangerously spiraling environmental crisis.

Lebanon’s problems are more directly linked to the failure of the political elite to resolve fundamental structural problems of a faltering economy and a dangerously spiraling environmental crisis.

Lebanon is facing its worst national debt ever, a result of heavy borrowing after the civil war ended in 1990, and a failure to stimulate enough growth and invite new investments. At $85 billion, the debt has essentially doubled in the past 10 years and a sluggish and corrupt bureaucracy has failed to fix the broken system of basic services, namely electricity, water, and the treatment of refuse. Such measures are also needed to persuade international donors to release $11 billion in pledged aid contingent on actions by the Lebanese government, including cutting subsidies and adopting much needed reforms.

Postwar governments have done very little to rebuild Lebanon’s infrastructure and, as a result, these basic services have not been restored to prewar levels—let alone modernized in order to meet the burdens of a burgeoning population and a large inflow of refugees from neighboring Syria. The main reason for this failure is not the lack of technical expertise but a stubborn and endemic corruption.

Effects of US Sanctions

US sanctions on Hezbollah started under the Obama Administration but have been tightened by the Trump Administration to include specific Hezbollah leaders and presumed financiers of the party. These sanctions have imposed cumbersome rules and procedures on any bank operating in Lebanon, which has made the Lebanese financial environment less hospitable to foreign investments.

Once a leader among the financial institutions of the Middle East, the Lebanese banking system now has to be totally open to being probed for any dealings with individuals or institutions that may be helping Hezbollah to evade sanctions. This pressure, added to a flailing economy, has caused a drop in the rating of some of Lebanon’s largest banks.

Rather than driving a wedge between Lebanon’s more traditional political parties and Hezbollah, the latest sanctions seem to be solidifying the alliance between the country’s largest Christian party, President Michel Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement, and Nasrallah’s party.

Rather than driving a wedge between Lebanon’s more traditional political parties and Hezbollah, the latest sanctions seem to be solidifying the alliance between the country’s largest Christian party, President Michel Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement, and Nasrallah’s party. Aoun strongly urged the US administration to reconsider its policy of sanctions, saying that they have a negative impact on Lebanese banks. Prime Minister Hariri, the leader of the March 14 bloc that opposes Hezbollah, also lamented the most recent sanctions imposed on his rival and said that they would not change the way his government conducts the country’s banking system.

Nasrallah’s latest address* on July 26—not unlike others before it—insists that internal as well as regional stability is in his party’s interest. He nevertheless stresses the party is fully capable of defending its interests against all enemies should push come to shove. He warned that Hezbollah fighters would return to Syria in even greater numbers than before should they be requested to do so. Nasrallah also warned that although a war with Israel was exceedingly unlikely in his opinion, the most vulnerable areas of Israel were easily reachable by Hezbollah missiles and that Israel was well aware of that.

Lebanon has survived since its independence in 1943 on a formula of coexistence through consensus among all its religious and political factions. The only time the republic came near total collapse was during the civil war, when that consensus was shattered. Current pressures on Hezbollah coincide with tense and dangerous times in the region. Rather than leading to a favorable change, if attempts to upset the delicate balance of power internally or in the region are successful, they would more likely lead to a potentially devastating explosion in Lebanon with unpredictable consequences.

* Source is in Arabic.