The Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) (al-Hashd al-Shaabi) has played a significant role in defeating the so-called Islamic State (IS) in Iraq. Thus, it has already gained popularity and esteem among Iraqis. In the context of upcoming national and provincial elections in April 2018, multiple and conflicting Shia parties are vying to benefit from the PMF’s reputation, translating field victories into political scores.

Originally, the PMF was formed as a national volunteer defense body after the Iraqi Shia authority, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, called all able-bodied men to arms to compensate for the failure of Iraqi Security Forces against IS in 2014. Although Sistani’s edict employed careful language that avoids sectarianism, the PMF structure incorporated many groups including formerly established sectarian paramilitaries. Estimated at between 60,000 and 140,000 fighters and consisting of a wide array of distinct groups and up to 50 regiments, the PMF is not monolithic. Yet, the overwhelming influence of Iranian-backed militias within the PMF structure has raised the question of the future role of Shia militias as the war on IS enters its final chapter in Iraq. Last year, in hoping to incorporate PMF militias into the Iraqi national army, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi led the effort to pass a law that put the PMF under the state’s command—a step that was protested by Sunni lawmakers because it legitimized the militias.

Historical competition between the two Shia centers—namely Iran’s Qom and Iraq’s Najaf—is visible among PMF groups. The groups that swear allegiance to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei push for a permanent privileged status for the PMF, whereas the groups that are loyal to Iraqi spiritual leader Sistani demand full integration of the PMF into the Iraqi Army while they also consider disbanding the force. A third major group within the PMF is the Sadrist movement, comprised of Iraqi Shia who view Iranian-backed groups as a serious threat to Iraqi unity; therefore, they call for immediate government oversight by “placing weapons in the state’s hands exclusively.”

A closer look at the PMF’s structure suggests that full integration of all PMF groups into the Iraqi security apparatus will be a challenging task for the Baghdad government. What follows is a general classification based on the various groups’ ideological underpinnings.

1. Pro-Qom Militias

The PMF’s leadership cadre does not reflect the organization’s rich diversity as the most powerful groups have close ties to Tehran. For example, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the PMF deputy chairman, is the founding father of Kata’ib Hezbollah (Hezbollah Brigades), which is listed as “terrorist” by the United States for being a direct arm of the IRGC’s (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) Quds Force in Iraq since 2007. Another PMF leading figure is Hadi al-Amiri, who commands the Badr Organization.

The Badr Organization and Kata’ib Hezbollah are two different models of Iran-backed Shia militias. Formed as the “Badr Corps” in 1982, it is the oldest Shia militia in Iraq. Until it was renamed as the Badr Organization after the 2003 American invasion, the militia was a subunit of the IRGC and acted as the armed wing of the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI). In 2007, under the leadership of Ammar al-Hakim, SCIRI renamed itself the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI) and has gradually moved closer to Ayatollah Sistani, turning away from Tehran. Badr’s leader Amiri rejected Hakim’s strategy and the Badr Organization denounced ISCI by reestablishing itself as Iran’s best ally in Iraqi politics. Thanks to then-Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, Amiri became the minister of transportation in 2010 and the Badr Organization began to play a larger role in Iraq.

Badr’s march to a political platform was remarkable even though the group’s militias were not disbanded. In 2014, the Badr Organization participated in the Iraqi elections as a part of Maliki’s State of Law Coalition, winning 22 parliamentary seats (out of 328). The group has also boosted its armed power since then due to its fight against IS in both Iraq and Syria. In May 2015, Badr politician Muthanna al-Tamimi became the governor of Diyala province, where Shia are a minority. To reach out to the larger Iraqi Shia community, Badr emphasizes its local identity. For instance, the group’s expeditionary force to Syria was named after Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr (1935-1980), who was among the founding fathers of the Dawa Party—the oldest Shia political party in Iraq. Political power play has enabled Badr to exert significant influence over the Ministry of Interior, where seventy percent of personnel have allegiance to militias, and Badr in particular.

Unlike Badr, Kata’ib Hezbollah does not participate in the Iraqi political system. The group was established to fight against US forces in 2007 when ISCI and Badr promoted transformations in Iraqi politics by cooperating with the United States to a certain extent. In the past decade, the IRGC has founded, trained, and supported many militias in the model of Kata’ib Hezbollah, including Saraya Khorasani and Kata’ib Abu Fadhl al-Abbas. Such groups protect Iran’s border areas and help in advancing Tehran’s corridor to the Mediterranean.

In between the Badr and Kata’ib Hezbollah models lies Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH), a major Shia militia that was heavily involved in attacks against coalition forces and the Baghdad government until 2011. AAH played a key role in helping Maliki’s consolidation of power between 2011 and 2014. As a result of joining the 2014 elections, AAH’s political wing, al-Sadiqun, won a seat in the Iraqi Parliament. Despite its interest in political activism, the group overtly displays its pro-Iranian identity—distributing, for example, thousands of Ayatollah Khamenei posters. Under the PMF umbrella, AAH has employed the most aggressive sectarian discourse and was accused of atrocities against Sunni civilians.

Despite diverse strategies and tactics, all aforementioned groups believe in Ayatollah Khomeini’s doctrine of wilayat al-faqih (guardianship of the jurist) and swear allegiance to Ayatollah Khamenei.

2. Pro-Najaf Militias

The PMF groups that have allegiance to the Iraqi Shia authority Ayatollah Sistani have also played a significant role in defeating the Islamic State. These groups were formed as an outcome of Sistani’s call for jihad against IS following the fall of Mosul to Sunni insurgents in June 2014. Sistani feared that Shia holy sites were endangered by the Islamic State; thus, the militia groups were named after major holy shrines in Najaf, Karbala, and Kadhimiyya.

Beyond ideology, what distinguishes pro-Najaf groups from pro-Qom militias is their willingness to disband or to be integrated into the Iraqi security apparatus in the future. The spokesperson of the Abbas Division, for example, strives for incorporation into the Iraqi Army: “All of the units, brigades and companies should join the Iraqi Army…There are a large number of Hashd al-Shaabi members who would go back to their civic duties within the Iraqi institutions.” Unlike the Tehran-backed militias, pro-Najaf groups acquire their weapons and training solely from the Iraqi Army. Their emphasis on Iraqi identity has opened the door to further popularity and legitimacy. The Ali al-Akbar Brigade is a case in point; the group even succeeded in recruiting Sunni Arabs in the fight against IS. Indeed, about 16 to 20 percent of the militia is Sunni.

Among the significant supporters of Ayatollah Sistani is ISCI. After Badr’s breakaway from the group, ISCI leader Ammar al-Hakim established new militias including Saraya Ashura, Saraya al-Jihad, and Saraya al-Aqida. Hakim recently stepped down from the leadership to establish a new party, the National Wisdom Movement, for the 2018 elections.

3. Pro-Sadr Militias

A third category within the PMF that has allegiance neither to Qom nor Najaf is Muqtada al-Sadr’s Saraya al-Salam (Peace Regiments). In post-2003 Iraq, Muqtada, the son of Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Muhammad Sadiq al-Sadr (1943-1999), has become a leading figure of Iraqi popular nationalism and Shia resistance. The Sadrist movement organized the Mahdi Army, carrying out numerous attacks on coalition forces and cultivating close relations with Tehran. In the past few years, however, Sadr’s relations with Iran have soured severely. From criticizing the Assad regime to paying a visit to Riyadh, Sadr reinvents his brand as Iraqi nationalist Shia, and accordingly, stands out from competitor Shia leaders to gain wider support.

Although Saraya al-Salam works under the umbrella of the PMF, the group does not receive strong funding and weaponry compared to other militias due to Sadr’s anti-Iran and anti-Maliki stance. Sadr demands disbanding the PMF—which he calls “imprudent militias”—after defeating IS. The power of the Sadrist movement stems from the fact that the group effectively appeals to ordinary Iraqis and was never part of the diaspora elite who returned to the country following the American invasion. Sadr was not personally nominated in any Iraqi elections; however, his movement now commands 34 seats in the parliament. Irritated by Sadr’s recent visit to Saudi Arabia, Iran claimed that pro-Sadr militias have been irrelevant in the fight against IS and thus, in their view, this makes Sadr not qualified to talk about the future of the PMF.

The PMF’s Critical Role in the 2018 Elections

The volunteer sacrifices and battlefield victories of PMF groups led competitive parties to reap the benefits from the PMF’s popularity. Even Prime Minister Abadi, who aims to bring the PMF under state control, swiftly protested Sadr’s call to disband the PMF, vowing to keep the groups active for several more years and increase wages of the fighters “despite some people’s attempt to oppose them.” Abadi’s approval rates have steadily surged in relation to the success in the war against the Islamic State. A reliable nationwide poll in April 2017 indicated that Abadi enjoys 59 percent of popular approval, compared to 33 percent in January 2016.

Now, a plethora of newborn parties have entered the electoral scene, since Iraqi law bans armed militias’ participation in elections. Thus, PMF organizations have formed parties under new names. According to Iraqi media reports, dozens of small parties have registered for municipal elections, most of them associated with certain PMF militias. Some major actors, such as the Badr Organization, have developed know-how as they participated in the 2014 elections and already have parliamentary seats. Others, like the AAH, even succeeded in registering for the elections without changing their names.

Former Prime Minister Maliki has long been very ambitious in supporting the PMF and aims to return to the premiership. In his second term (2010-14), he chose to embolden Iranian-backed militias to secure his position, partially due to the rise of al-Iraqiyya—a party of the secular Arab coalition—at the expense of Maliki’s Dawa Party. Upon approving the PMF through his fatwa, Sistani demanded Maliki’s resignation, even though Maliki won an outright election victory in 2014 elections. Abadi, another Dawa politician, replaced Maliki after complicated negotiations.

Maliki’s strong alliance with Badr’s leader Amiri will play a critical role in the elections. Under Amiri, political wings of pro-Qom militias—including those of Kata’ib Hezbollah, AAH, Kata’ib Jund al-Imam, and Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada—recently agreed to unite under the “Coalition of the Loyalists” and initiated their election campaigns by launching professional public relations efforts via traditional and social media. Although these Iranian-backed groups do not represent all PMF units, they capitalize on the PMF’s popularity in the eyes of Iraqis, and thus, demand a permanent special status for the PMF in Iraq’s future.

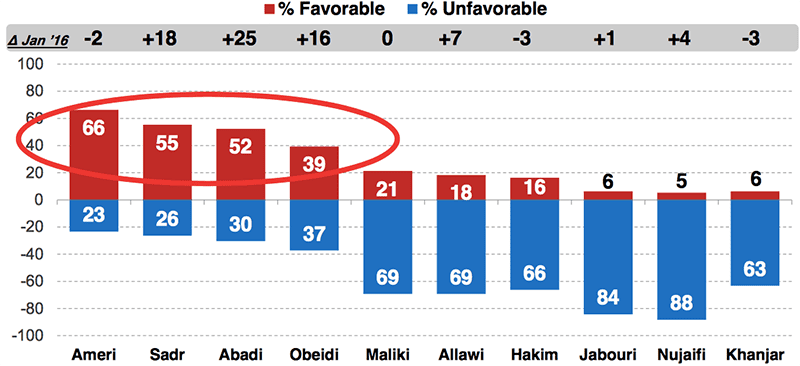

Given that the United States has strong concerns about the future of the PMF as an independent body in the mold of Hezbollah in Lebanese politics, Washington and Tehran are on opposing sides in Iraqi elections—a historic first since the American invasion in 2003. Washington has cultivated good relations with Abadi, who now finds himself between the forces of Sadr and the Maliki-Amiri alliance. Opinion polls indicate increasing popularity of both Sadr and Amiri in Iraqi politics (see Table 1 below). The Sadrist movement has recently reached an agreement with Iyad Allawi’s al-Wataniyya to form a coalition for the elections. Even if Abadi remains in power after the elections, the level of voter confidence in Sadr and Amiri will be significant in shaping the PMF’s future. If Sadr’s pitch for Iraqi national identity is not going to attract masses and Amiri reaps the benefit, Abadi will have a difficult time integrating the Badr Organization and other pro-Qom militias into the Iraqi Army.

Table 1. Changing fortunes between National Democratic Institute poll results in April 2017 in Iraq (excluding Iraqi Kurdistan) in comparison with an earlier poll in January 2016.

A wild card in the puzzle concerns pro-Sistani groups such as Hakim’s National Wisdom Movement. Although such groups are in favor of disbanding PMF militias, they are not likely to form electoral alliances with the Sadrists due to historical rivalry. Thus, in a highly competitive environment, Ayatollah Sistani’s opinions may bring more weight—despite the fact that Sistani often avoids involvement in everyday politics.

More important than ever are Washington’s reconciliation efforts to save Iraqi unity and promote an integrated, nonpartisan national army. Beyond the war on IS, the Abadi government needs strong US support for improving state institutions, including judicial and legislative bodies, that will result in a healthy system with checks and balances. Washington is not called upon to undertake a comprehensive state-building project, unlike its role in the Syrian puzzle; and it is indeed well-positioned to lead Iraqi efforts for national unity after the 2018 elections. Given that the distribution of power among Iraqi parties has been most diffuse and shared, US-led efforts for institutional strength are imperative for long-term stability. Until then, however, Iraq will continue to face the risks of sectarianism and political turmoil.