In a high-stakes visit to Brussels on January 22, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas sought European Union (EU) support for a path toward Palestinian statehood. It is not the first time Palestinians believed they could benefit from the US-European divide to advance their quest for statehood, but what is different this time is that President Donald Trump is in office. Transatlantic relations are currently strained and US and European interests are contradictory on a myriad issues, from climate change to Iran’s nuclear deal. Incidentally, Abbas’s visit to Brussels coincided with that of US Vice President Mike Pence to Israel. The contrast in those split screen images illustrated the emergence of a nascent Palestinian-European partnership aiming to reign in the United States’ influence in the Middle East peace process. However, the Palestinian wager on the EU could provide an opportunity for the Trump Administration to contain Palestinian anger and move beyond the US decision in December to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.

Abbas’s Rhetoric from Ramallah to Brussels

Mahmoud Abbas and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) are at a crossroads; their legitimacy has been questioned in the past decade by three main developments. First, Fatah’s decision to revoke the October 2006 parliamentary elections, which led to the split between the West Bank and the Hamas-led Gaza, had a profound toll on the Palestinian leadership’s structure. Second, the status quo of the Israeli-occupied West Bank predetermined the Palestinian need to depend on Israel for security coordination and economic survival. Third, the lack of a genuine US effort to launch a credible peace process led to a political void in the West Bank as, since 1993, the PLO has redefined its role from resisting Israel to achieving Palestinian aspirations through peace negotiations.

Abbas arrived in Brussels carrying a clear mandate from the PLO’s central committee, which met last week to discuss the way forward in dealing with Trump’s decision on Jerusalem. The resolutions announced on January 15 addressed two of the three above-mentioned challenges; Israel’s occupation and the US role, however, left out a roadmap for Palestinian reconciliation. Both Hamas and Islamic Jihad were not present at the meeting because of their inability to reach the Israeli-occupied West Bank.

The final communiqué,1 which included harsh wording against the United States, talks about “aborting” Trump’s decision on Jerusalem and notes that the United States “has lost its credibility as a mediator and sponsor of the peace process.” It also suggests an international peace conference in coordination with the European Union, Russia, and China while hinting that Arab countries should sever ties with the United States. The PLO declared the end of all Palestinian commitments under the Oslo Accords. It also suspended the Palestinian recognition of Israel until Tel Aviv recognizes the Palestinian state within the 1967 borders, cancels the decision to annex East Jerusalem, and halts settlements in the West Bank. These popular provisions that prompted the Palestinian president’s trip to Brussels now face the harsh reality of the global order. Abbas toned down the rhetoric while meeting EU foreign ministers and renewed commitments to previous agreements with Israel. He reiterated the call for the EU to recognize Palestine, assuring that such a move would not impact future negotiations with Israel.

Where the EU Stands on Palestinian Statehood and the International Framework

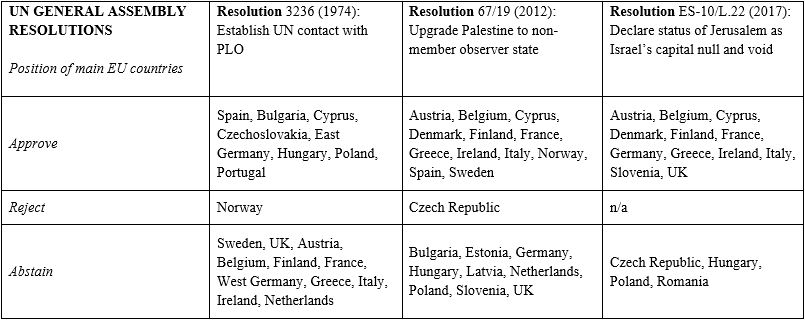

Since the Palestinians began to seek international recognition of their state three decades ago, the European stance has evolved. The 1999 Berlin Declaration was the first EU document to endorse the idea of Palestinian statehood. In July 2009, the EU foreign policy chief called on the UN Security Council to set a deadline for recognizing the Palestinian state. In 2011, Abbas asked the EU to press ahead on a UN resolution to recognize the State of Palestine; however, European countries were and remain divided over the issue. Past experiences show that the EU as an institution is willing, instead, to criticize Israeli settlements, as they did in October 2014. However, there is no European consensus when it comes to recognizing Palestinian statehood, as highlighted in the table below.

The EU foreign policy decision-making process, built on consensus among the 28 members, poses a challenge for the Palestinians. Decisions related to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict often require arm-twisting in Brussels. In January 2016, Greece was the last holdout before folding under European and Palestinian diplomatic pressure, which allowed the EU foreign affairs council to adopt a resolution criticizing Israeli settlements. Tel Aviv’s strategy, in return, has been to focus on lobbying a handful of EU members to break the consensus. While there is European sympathy for Palestinians, that should not be read as an endorsement of statehood. Although EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Federica Mogherini considered Trump’s decision on Jerusalem as “a very diplomatic euphemism,” there was little support among European foreign ministers for Abbas’s call to officially recognize the Palestinian state.

However, that institutional reluctance to recognize Palestine is balanced by a growing number of individual European countries willing to take that step. Sweden was the first EU member in western Europe to do so, in October 2014, and seven other European countries had recognized Palestine previously, in 1988 through a UN General Assembly resolution. Slovenia is expected to recognize Palestine next month while Luxembourg, Ireland, and Belgium might follow suit. France is under parliamentary pressure to recognize Palestine but the French government is cautious and wants to maintain cordial relations with Washington. Instead, French diplomacy is pushing for an EU free trade deal with the Palestinian Authority.

The second challenge after statehood is the international framework to advance peace talks between Palestinians and Israelis. The Middle East Quartet has met twice so far since Trump took office, most recently last week with US Special Envoy for Middle East peace Jason Greenblatt in attendance. The Palestinians have shown flexibility after Mahmoud Abbas’s visit to Brussels. A senior Palestinian official noted that Ramallah is open to Washington taking a role within a multilateral framework as long as Washington is not the sole sponsor of peace talks with Israel. Palestinian officials continue to boycott US officials since Trump’s decision last month to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. Palestinians are suggesting to either keep the current Middle East Quartet or create a new model, one that includes the five permanent members of the Security Council. Mogherini told reporters in Brussels that the Middle East Quartet could be expanded to add a few Arab countries and possibly Norway.

Indeed, the EU is pushing back on the US recognition of Jerusalem on two tracks: on the institutional track by asserting a “central role” for the EU in the Middle East process; and by leaving individual members of the EU to decide whether they should recognize Palestine or not—which will increase public pressure on Israel.

How Should the Trump Administration React?

The United States has recently exerted significant pressure on the Palestinians, from hinting that the PLO office in Washington should close to cutting UNRWA funding. The Europeans are trying to contain the fallout of Trump’s Jerusalem decision by inviting both Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Mahmoud Abbas as well as Arab League representatives to Brussels next February. For his part, Netanyahu insists on maintaining the US role as a peace broker; he affirmed on January 22 that, “There is no alternative for American leadership in the diplomatic process. Whoever is not ready to talk with the Americans about peace—does not want peace.”

US policy-makers could consider four policy options to help restore balance to the Middle East peace process:

- The United States would be wise to embrace the EU’s plan to play a “central role,” along with Washington, in the peace process. If the EU becomes a guarantor for Palestinians, this would ease the pressure on Washington and allow mediators to focus on drafting a peace plan.

- Floating peace proposals by Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, that disregard the US establishment—as well as key regional players like Jordan—have proven to be counterproductive. Engaging the international community and Arab allies in an inclusive approach remains the best way forward.

- The good standing the Trump Administration has with Netanyahu should help Washington persuade the Israeli government to recommit to peace talks within the updated international framework. While the Trump Administration aims to prioritize Israeli interests, there should be recognition that America’s influence is waning and Washington alone cannot enforce a peace on either the Palestinians or the Israelis.

- US-Palestinian tensions do not serve either side, and there should be mediation to restore minimal engagement. Jordan could play a key role in that effort.

Several factors are in play in this latest diplomatic gambit. Abbas’s move is as much about foreign policy as it is about Palestinian politics, in light of his leadership facing a legitimacy crisis in the past years. Fatah is also cutting the road on its rival Hamas by revitalizing its central role in the Palestinian struggle. Abbas’s main messages in Brussels were committing to peace talks with Israel and to Palestinian national reconciliation, which are the two main European demands. Indeed, a fractured territory cannot transform into a state: uniting the Palestinian territories politically and working to end their economic reliance on Israel should be the Palestinian Authority’s top priorities.

Most of the Palestinian attempts to achieve statehood have been symbolic so far. In a speech on December 13 before the extraordinary meeting of Islamic leaders in Istanbul, Abbas signaled the Palestinians would go to the Security Council to seek full UN membership—an unlikely move that would not change Palestine’s status as a non-member “observer.” The reality is that because of Trump’s decision on Jerusalem, no Arab or European country would cut ties with the United States or challenge Israel to recognize Palestinian aspirations. Even Jordan has recently patched up relations with Israel.

The Palestinian bet on Europe is an effective pressure tactic, but it will not achieve statehood as a stand-alone policy. Most importantly, Brussels is gradually becoming the mediator between the Palestinians and the Americans. Boycotting US officials is detrimental for Palestinian interests as Ramallah risks losing the residual support it has among the US establishment. In Washington as well, a return to a traditional rather than a confrontational approach to the Middle East process is long overdue. The fact that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson prevailed over US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley regarding the UNRWA funding policy debate could be a step in the right direction.

With Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan facing their own challenges and unable to take an effective leadership role in the peace process, the EU is filling the void and adding a new portfolio to its Middle East policy effort. The fact that the Palestinians are turning to Europe is an opportunity for the Trump Administration to mitigate the negative impact the Jerusalem decision left on US policy in the Middle East. While peace between Palestinians and Israelis is elusive in the foreseeable future, launching a peace process could be the only alternative to prevent the inevitable violence that could erupt if the United States remains disengaged. Brussels just threw a diplomatic lifeline, so Washington should seize the moment.

1 Source is in Arabic.