The inevitable has proved itself in Kirkuk: the intense crisis precipitated by the short-sighted and unconstitutional September 25 Kurdish referendum seems to have opened a new chapter in the Baghdad-Irbil standoff. The insistence by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) president, Masoud Barzani, on holding the referendum antagonized the Iraqi central government and people as well as Turkey and Iran, Iraq’s immediate northern and eastern neighbors, respectively. Barzani’s insistence was also received with disapproval from the international community, including the Arab world and the European Union, the United States, and the United Nations Security Council. The government in Baghdad offered to hold negotiations over the pending problems with Irbil, provided that Kurdish authorities rescind their referendum plan to avoid its serious implications.

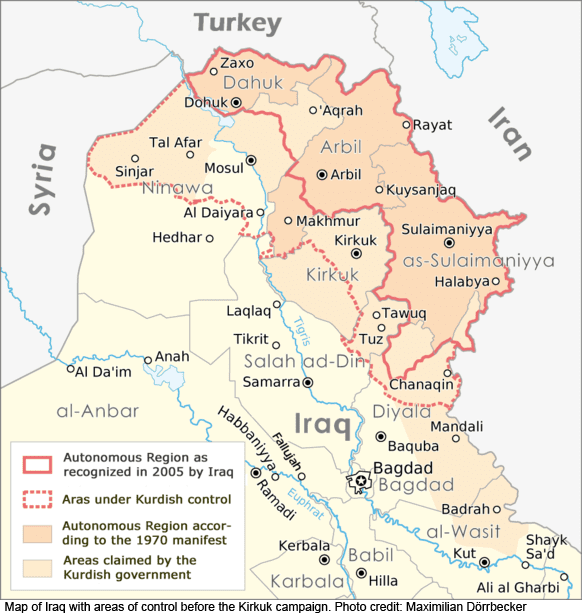

Relying on domestic support, constitutional legitimacy and legality, and international backing, Baghdad demanded the handover of international airports and border crossings to federal authorities no later than Friday, September 29. The Iraqi federal government also opted to redeploy its forces to their prior positions in and around Kirkuk and its vicinity, and started their operations by the end of the second week of October. Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi stated that the forces had no intention of waging a war against the KRG and asserted that their sole goal was to reestablish federal control over Kirkuk and other disputed territories that the KRG had occupied unconstitutionally, some since 2014 and others after liberation from the so-called Islamic State (IS).

In reality, Kirkuk is not a Kurdish city, although it has a sizable Kurdish community, just like the Turkmens and the Arabs. After occupying Kirkuk, Kurdish authorities started a process of ethnically converting it into a Kurdish city, one that was challenged by the other communities. Ironically, they had criticized Saddam Hussein when he carried out similar practices. In fact, Kirkuk has always been a predominantly Turkmen city, even before the extraction of oil from the area during the 1920s.

After the Iraqi Army deserted the region in 2014 and the Kurdish forces occupied it, peshmerga forces loyal to Barzani controlled the Baba Gurgur, Bai Hassan, and Aliana oil fields, sites of the second richest reserves in the country. They immediately began illegally pumping oil from the fields, disregarding a Memorandum of Understanding with Baghdad stipulating that the federal State Organization for Marketing of Oil (SOMO) markets all the exported oil, with the KRG’s share credited through the federal financial apparatuses. Peshmerga forces loyal to the late Iraqi president, Jalal Talabani (a Kurd), imposed their control over the city of Kirkuk and its surroundings and exercised full control over administration in the area since the governor was a member of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK).

Iraqi forces backed by the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), the Shia militia led by Hadi al-Amery—a pro-Iranian warlord subordinate to General Qasem Soleimani of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)—started to mass around the Kirkuk region awaiting further orders. From his side, Soleimani exploited Iran’s close relations with Talabani and exerted pressure over the PUK peshmerga to hand over Kirkuk to the federal forces. Indeed, Talabani’s peshmerga yielded to the pressure and withdrew from the confrontation with the Iraqi Army. This left Kirkuk, the oil fields, the military complex, and the refineries open to the Iraqi central forces and the PMF, which took advantage of what happened and thrusted into the city, controlling vital areas and imposing an overnight curfew. The governor, who had been ousted by the Iraqi Parliament but refused to yield, fled leaving his protective forces to their destiny. The Iraqi government has since appointed Rakan Saeed as his replacement.

Barzani’s peshmerga units and their affiliated volunteer fighters, supported by forces from the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Syrian Kurds’ People’s Protection Units (YPG)––who were allegedly brought in by Barzani––were caught unawares and fled the front or were ordered to withdraw. Allegations of treason started to be used against Talabani’s peshmerga, and the old and hidden Barzani-Talabani feuds began to reappear, perhaps indicating difficult times ahead for the KRG. Many thought that this was payback and retaliation by the Talabani forces for Barzani’s collusion with Saddam Hussein’s army against them in August 1996. Then, the Iraqi Army succeeded in defeating the Talabani faction and expelling it not only from Irbil but also from its stronghold Sulaymaniyah. In fact, Talabani was forced to take refuge on the Iraq-Iran border. What transpired in the Kirkuk battle seems to be the same scenario in reverse fashion.

It seems from the developments of the Kirkuk battle that a deal was struck between the Talabani family’s PUK members and the federal government to hand over Kirkuk and other disputed areas under peshmerga control to the federal forces. Talabani’s peshmerga started to pull out of the city and other strategic areas to pave the way for the federal troops, supported by the PMF, to take over. It also appears that the deal was planned and ordered by Soleimani, who is said to have supervised the operation on the ground.

Barzani accused Baghdad of conspiring to retake Kirkuk. From its side, Iran denied its direct involvement in the events. It seems that Barzani has lost the battle so far and was assailed by many Kurds for pushing the situation toward this end. The new developments in Kirkuk make a Kurdish independent state under his leadership a farfetched dream, if not entirely impossible. Calls have increased on Barzani to resign as president of the KRG.

The current situation further suggests that the KRG may well be divided into two regions: one consisting of Irbil and Dohuk under Barzani, and the other made up of Sulaymaniyah, Halabja, and the Kurdish parts of Kirkuk under the control of the Talabani family. Pavel Talabani, the son of the late Jalal Talabani, made a televised speech on Monday, October 16, in which he indicated that a deal was struck to that effect with the central government. In short, the old KRG may now be history.

The latest developments did not stop at Kirkuk. Almost all the disputed territories in the Mosul Plain (otherwise known as the Nineveh Plain)––a majority-Christian territory that was controlled by Barzani’s peshmerga––was also deserted and subsequently occupied by government forces. The same occurred on the western bank of the Tigris River, as it enters Iraq from Turkey, and the Yezidi-inhabited Mount Sinjar area that was controlled by a Yezidi militia loyal to Barzani.

On Tuesday, October 17, Masoud Barzani issued a statement to the Kurds accusing some politicians from a certain party (presumably the PUK) of responsibility for what happened in Kirkuk. In the same statement, he assured the Kurds that he would defend and preserve their rights. The outcome shows that Barzani is now on the defensive and his sole aim is to protect Irbil against a possible thrust by the victorious Iraqi troops, especially after news spread of a troop buildup close to the city. Operations seem to be bloodless thus far; but threatening Irbil may light the fuse for an open war between antagonistic factions fighting amongst themselves.

It now appears that KRG authorities may have opted to pull back to the 2003 blue line separating it from Iraq proper and giving it control over 13 percent of the country’s total territory. Baghdad now is exercising full control over the so-called “disputed territories” with their mixed populated areas to the south of the separation line. The fate of Article 140 of the constitution, which supposedly determines the control over these areas, is currently unknown. But given the differences between the parties and the potential for great conflict, it may be more logical and cost-effective if they are under the control of the federal government while the local population elects its representatives according to established procedures.

Both the central government and the KRG should engage in negotiations to discuss and resolve the challenges and problems that face the country. Egotistical behavior and the desire to control are Iraq’s evils. Working together is the challenging task for all to end Iranian meddling in Iraqi affairs, check both chauvinism and sectarianism, and address the numerous problems the country has endured since the 2003 invasion and occupation. All Iraqis face and suffer from the same ailments: chauvinism, sectarianism, and failed governance, including corruption and incompetence. Recognizing the cultural and political rights of all the components of Iraqi society, meeting the legitimate aspirations of the people, and refraining from exaggerated demands will prevent the collapse and destruction of the country.