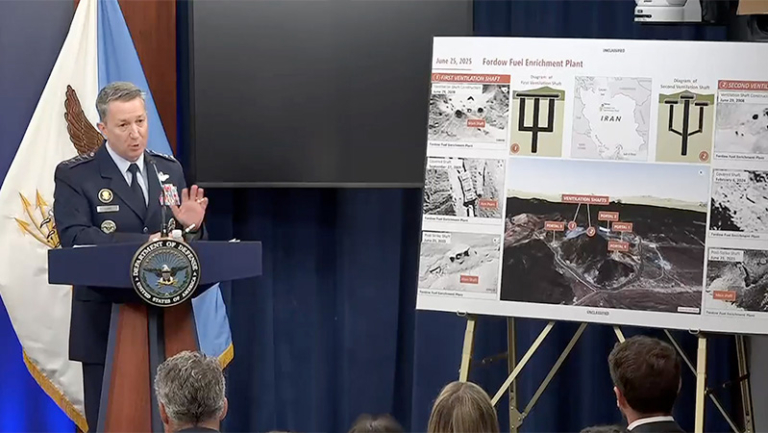

Years of shadowboxing and increasingly direct skirmishing between Israel and Iran erupted into 12 days of conflict that began in the early hours of June 13 and ended, for now, with President Donald Trump’s declaration of a fragile ceasefire on June 24. Direct American involvement in the June 22 airstrikes against Iranian nuclear facilities at Natanz, Isfahan, and Fordow, and Iran’s retaliatory launch of some ten ballistic missiles at the United States’ al-Udeid Air Base in Qatar the following day, placed the Gulf states firmly in the crosshairs of a war that they had long sought to avoid. As the dust begins to settle on the fighting that came closest to regionalizing the post-October 7 wars, policymakers’ attention will focus on implications for stability and security in the Gulf.

For more than two decades, officials in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states have maintained a delicate balancing act as they hosted a US military footprint that expanded significantly in the 2000s with the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. While the network of US force deployments, bases, and logistical arrangements is a critical component of GCC states’ security and defense posture, the American presence also risks involving the Gulf countries in any escalation of regional tension with Iran. Thus, GCC officials have periodically signaled that they would not permit the United States to use facilities in their countries in any attack on Iran.

Cracks in the Regional Equilibrium

The decade from the end of the Obama administration through Trump’s first term and into the Biden interregnum saw a series of cracks in the geopolitical equilibrium that cumulatively injected doubt into the perceived value and durability of extant regional relationships. From the whipsaw nature of US policy toward Iran and nuclear negotiations in the 2010s to the White House responses to the blockade of Qatar in 2017 and two years later the Iranian-linked attacks on maritime and energy targets in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the reliability of an American-led regional status quo came in for questioning.

Partly in response, the GCC recohered in 2021 and launched a regionwide process of rapprochement and de-escalation, including with Iran, and largely declined to be drawn into US competition with Russia and China. Such has been the determination of policymakers in the Gulf states to straddle the fractures in global geopolitics that observers have identified a spirit of non-alignment on the world stage, evident in their stances toward the Russia-Ukraine war and the steady growth of relations with China. Meanwhile, the ferocity of Israel’s war on Gaza and a desire to avoid the conflict’s regionalization led to a continuous dialogue between Gulf leaders and their Iranian counterparts as the GCC states emerged to lead regional mediation and diplomacy.

Lessons of US Military Engagements

With the above in mind, what lessons may be drawn from the 12 days of conflict that brought the region to the brink of a scenario long dreaded by many in the GCC? It was notable that the US strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities were carried out by bombers that flew from the United States and by cruise missiles fired from a submarine, rather than by any of the military assets positioned in the Gulf states. Similarly, the United States and United Kingdom launched their 2024-25 strikes against Yemen’s Houthis from aircraft carriers and submarines as well as from bases in Cyprus rather than from facilities in the Gulf. Whereas the US decision not to use Gulf-based military assets was mindful of regional dynamics, it has led isolationist voices in the United States to ask why the forces are stationed in the Gulf if they cannot be used in such missions and are sitting ducks for retaliation. For US officials and their Gulf partners, however, the decision not to use Gulf bases stemmed from a desire to minimize the Gulf’s exposure to Iranian responses. The United States and its Gulf partners also wanted to avoid Iran’s ‘gray zone’ activities, such as its alleged 2019 targeting of shipping near the Gulf with limpet mines, hitting Saudi Arabia’s East West pipeline, and striking critical Saudi oil infrastructure with missiles and drones.

Iran responded to the US attack and in a way that created a new precedent.

Iran did respond to the June 21 US attack and in a way that created a new precedent, even as it carefully managed its June 23 launch of missiles against the al-Udeid. The targeting of a base hosting American forces (and its advance telegraphing) was reminiscent of Iran’s January 2020 firing at military facilities in Iraq. On that occasion, which came after a surge in tension following the US killing of Iran’s Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani, the Iranian leadership retaliated against American forces in Iraq. This time, the Islamic Republic’s decision to target al-Udeid, the largest and most important American base in the Middle East, carried greater symbolism. A line has been crossed that cannot be undone. The next time that the Iranian command chooses to hit US interests in the Gulf (or their host nations more broadly) may not be in such a calculated off-ramp manner.

In January 2020, concerns about being caught in the middle of spiraling US-Iran tensions led the Saudis to send Deputy Defense Minister Khalid bin Salman to Washington and London to make the case for de-escalation in person. The message was supported by Emirati officials mindful of the damage to the UAE’s reputation as a safe place to live, work, and do business, as three Houthi drone and missile attacks on Abu Dhabi in 2022 vividly demonstrated. The June 2025 US-Iran flareup came amid intense regional diplomacy. While each GCC state condemned the Iranian attack on al-Udeid, their statements made clear that they viewed Israel as the aggressor as they called for restraint. In addition, statements from Qatar, the UAE, and Kuwait on June 23 blamed the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, rather than the Iranian state itself, for the attack on al-Udeid.

Two Essential Points

Two other points of note surfaced during the 12 days of conflict. The first is that excitable commentary about the potential for Iran to ‘close’ the Strait of Hormuz to shipping was as hollow as the threats—first made during the 1980s Iran-Iraq War—were repetitive. Iran does possess the capability to harass shipping passing through the strait, and freight rates and insurance costs did rise sharply as a result of the Israel-Iran war. But a full-scale disruption was never in the cards, not least because closure would have hit Iran’s main oil export terminal at Kharg, inside the Gulf, as much as it would have affected the Gulf States, including Kuwait and Qatar, whose oil and gas cargoes are almost wholly reliant on passage through Hormuz. Shipments of Iranian oil to China, its largest consumer, would also have been affected by action in the strait, which has never been fully closed. In any case, the shipping lanes pass mainly through Omani rather than Iranian waters, a fact missed in much of the chatter and likely a key element in Omani de-escalatory messaging with Tehran.

Nevertheless, any prolonged increase in the cost of shipping through Hormuz would have secondary effects on the Gulf states due to their reliance on seaborne traffic for imported goods, including most foodstuffs and many raw materials. Alternative overland routes are available, as well as ports on the Red Sea and the Gulf of Oman for Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Fujairah in the UAE. But the volume of goods entering the Gulf by ship, including to the hub of Jebel Ali for transshipment elsewhere, makes GCC states vulnerable to supply chain shocks that could hit their major economic and infrastructure projects. It is for this reason that officials throughout the Gulf, and especially in Riyadh, have put so much emphasis on ‘de-risking,’ as they can ill-afford disruption as the giga-projects associated with Vision 2030 move to implementation phases.

There is a sense that the conflict between Iran and Israel could have been worse, at least from the GCC’s perspective.

The second point of note from the June 2025 conflict was that Israel’s campaign largely bypassed Iran’s oil and gas infrastructure along the coastline of the Gulf, apart from a June 14 Israeli strike on a natural gas processing facility linked to operations at the South Pars gas field. Iran likely would have seen Israel’s attack on the jugular of Iran’s energy sector, as an existential challenge and a justification for a lashing-out of last resort, including by targeting the Gulf states’ own energy infrastructure. This did not happen. It is also a relief that the list of targeted nuclear facilities did not include the Russian-built Bushehr reactor. Officials have long warned of the catastrophic damage that could arise from any seepage of radioactive material into the Gulf and contamination of water supplies used in desalination plants.

There is thus a sense that the conflict between Iran and Israel could have been worse, at least from the Gulf states’ perspective, even though another step has been taken on an escalatory ladder that could still end with the scenario of a major regional confrontation. In addition, in the eyes of the Trump White House, Qatar ‘took one for the team’; it remains to be seen whether this strengthens Doha’s position in the face of Qatar’s detractors in Washington, including in Trump’s MAGA movement. For the leadership in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, the challenge is now how to impress upon the White House the need for stability in the region if Trump is to reap the trillion-dollar benefit of his May 2025 visit to the Gulf.

New Equilibrium Is Needed

A new balancing act may now emerge, as GCC states engage with an Iran weakened by its inability to prevent Israel and the United States from penetrating its air defenses seemingly at will and by the steady dismantling of key elements of the ‘Axis of Resistance’ which noticeably did not come to Iran’s support. A weaker Iran and a degraded set of regional proxies is undeniably an outcome favorable to Gulf states’ interests. But a new equilibrium is needed in the face of an Israel that Gulf states view as much of a challenge to regional stability as Iran and with the Trump administration’s expected pressure on other Gulf states (namely Saudi Arabia) to join the Abraham Accords.

The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

Featured image credit: x/DoD