On August 7, 2025, the Lebanese government met to discuss a proposal by US Envoy to Syria and Ambassador to Turkey Thomas Barrack that laid out the elements of a process for Hezbollah disarmament, for Israel’s withdrawal from areas that it occupies in South Lebanon and a halt to its attacks on the country, and for the organization of a conference by France, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United States to help Lebanon’s economy. Lebanon’s cabinet accepted the plan, but not before the Shia ministers left the meeting in protest. Two days earlier, in an unprecedented step, the Lebanese government ordered the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) to present by the end of August 2025 a plan to put all arms under the control of the state before year’s end. This plan places the onus for disarmament on the LAF and the government, not on Hezbollah, and the United States has made clear that until the party is disarmed, Lebanon will not receive urgently needed international aid. Hezbollah and its allied ministers in the government describe this approach as a shakedown, but considering Lebanon’s devastated economy, ongoing Israeli occupation, and the government’s lack of sovereignty over Lebanese territory, it is hard to see that the government has any choice but to comply.

Hezbollah’s Recent Weakening

Hezbollah emerged in the 1980s mainly as a response to Israeli attacks and invasions of Lebanon in 1978 and 1982. Its establishment, with backing from Iran, was rooted in preexisting socio-economic inequalities besetting Shia communities in the country. Since then, Hezbollah has grown stronger by receiving aid from Iran and Syria and by developing a clientelist network, as well as by continuing its resistance against the Israeli occupation of parts of southern Lebanon. But today, it is in a weaker position than ever before after the rise to power of a new Syrian government and the damaging repercussions of recent wars with Israel.

The collapse of the Assad regime in December 2024 delivered a further blow to Hezbollah as Iranian material support to the group via Syria was obstructed, impeding Hezbollah’s weapons procurement and nearly all of its missile supplies that have been crucial for its operations against Israel. The regime’s fall also curtailed Hezbollah’s ability to receive an estimated $700 million annually from Iran via Damascus. Meanwhile, the new government in Syria is understandably hostile to Hezbollah’s armed presence on its western border, since the group fought alongside the Assad regime during the 2011-2024 civil war.

The collapse of the Assad regime delivered a further blow to Hezbollah.

The loss of the Iranian supply line further weakened Hezbollah’s condition following the heavy human and material losses that the group endured during Israel’s invasion of South Lebanon in October 2024, from which the party is finding it difficult to recover. Since the end of those hostilities, Israel has broken its ceasefire agreement on a near-daily basis, further discouraging Lebanon’s war-weary Shia communities from enlisting in Hezbollah.

On the political front, Hezbollah finds itself relatively isolated. Its Shia allies in Lebanon’s Amal Movement have rejected calls to disarm on the timeline proposed by the United States, though Amal leader and Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri met with Barrack and described the meeting as “constructive.” Hezbollah’s other ally, the Maronite Free Patriotic Movement, has stated that it supports Hezbollah’s disarmament, as has the Armenian Tashnak party, whose cabinet minister stayed behind during the Shia walkout when the government approved the disarmament plan. The Lebanese public is not united on the question of disarmament: 58 percent oppose Hezbollah surrendering its arms without a new national defense strategy, which the government has yet to provide. Hezbollah nevertheless finds itself increasingly isolated in national politics as well as in the regional arena.

Prospects for Disarmament

Hezbollah and the Amal Movement have already deemed the plan proposed by Barrack and adopted by the cabinet as unacceptable. The Lebanese government now finds itself caught between the United States and Israel, which are pushing for full disarmament, and Hezbollah, which views total disarmament as dangerous to itself and to Lebanon as a whole. Although not a permanent solution, as an important step Hezbollah’s command structure should be integrated into the LAF where it will operate under democratic oversight. This would ensure that Hezbollah cadres are put to work for the protection of the entire population.

The LAF is the most trusted institution in the country and has largely escaped the corruption scandals.

The LAF is the most trusted institution in the country and has largely escaped the corruption scandals that have shaken public faith in many other parts of the state. However, because of the inability of the Lebanese government to properly pay soldiers—enlisted troops earn less than $100 per week and often work part-time jobs off base—the army cannot be deployed for an extended period. Even these meager salaries are entirely paid by foreign backers, in 2023 by the United States and more recently by Qatar. Lebanon’s lack of domestic arms production and the high cost of weapons on international markets exacerbate the LAF’s budgetary strain. European countries and the United States donate ammunition and replacement parts to Lebanon, making the logistics network for the LAF entirely dependent on governments that also arm Israel.

The economic cost of integrating Hezbollah fighters into the regular army would be considerable but it would allow the state to acquire Hezbollah’s military infrastructure in South Lebanon, where the LAF currently lacks capabilities. Hezbollah’s technology is also more advanced than the LAF’s equipment: the group possesses drones, newer infantry equipment from Iran, and Lebanon’s only domestic weapons production capacity. If Hezbollah’s materiel, especially its ammunition supplies, were to be centralized under LAF control, military provocations could be prevented and LAF logistics improved.

The worst-case scenario for disarmament, a hostile attempt to disarm Hezbollah, would leave thousands of the group’s trained personnel, previously able to sustain themselves through Hezbollah’s internal economy, to fend for themselves in Lebanon’s weak labor market. Moreover, any assumption that disarmament would immediately succeed is misplaced: an attempt that meets resistance could lead to a far bloodier version of the events of May 7, 2008, when the Lebanese government abandoned an attempt to curb Hezbollah’s power following major street clashes. Today, the government can no longer postpone tackling the issue.

Disarming Hezbollah is likely to require heavy involvement from the United Nations Interim Forces in Lebanon (UNIFIL), which has been weakened by a series of incidents that have sapped international willingness to provide peacekeepers. Yet this international support for the Lebanese government’s efforts is essential for peaceful disarmament. If the United States and its allies are committed to this process, they should show more willingness to compromise with Hezbollah on a ‘day after’ plan for the group’s fighters, giving the Lebanese government the flexibility that it needs.

Why Lebanon needs UNIFIL

Other than direct aid to the LAF, the primary mode of international engagement in disarmament is through UNIFIL, which is tasked with confirming the withdrawal of Israeli forces from South Lebanon, with monitoring the cessation of hostilities, and with assisting the LAF in deploying to the south. UNIFIL draws its mandate from the United Nations Security Council, which in 2006 charged it with helping the LAF to establish an area free of non-government weaponry in South Lebanon following the end of Israel’s 1982-2000 occupation, during which UNIFIL troops were attacked more than 30 times. Israel has repeatedly criticized UNIFIL over its failure to disarm Hezbollah, even though this task exceeds the forces’ mandate. During Israel’s 2024 invasion of Lebanon, Israeli troops attacked UNIFIL bases on multiple occasions, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called the peacekeepers a “human shield” for Hezbollah.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called the UNIFL a “human shield” for Hezbollah.

Despite Israeli claims of the UN’s acting on behalf of Hezbollah, UNIFIL turned over 225 Hezbollah weapons caches to the LAF between November 2024, when Israel and Hezbollah signed a ceasefire agreement, and May 2025. UNIFIL has also been successful in dismantling significant Hezbollah military infrastructure in South Lebanon. But this achievement has not stopped Israel from continuing its diplomatic offensive against the UN peacekeeping force. Israeli Minister of Foreign Affairs Gideon Sa’ar urged the United States to veto UNIFIL’s upcoming renewal vote at the UN Security Council on August 31, 2025. For Israel, UNIFIL’s efficacy in disarming Hezbollah seems to be less important than the fact of its impartiality, which impedes Israeli war aims in Lebanon.

As Israel grows more belligerent, the Lebanese people grow more concerned for their own safety. As it stands, UNIFIL is prohibited from engaging Israeli troops if they were to reinvade Lebanon. During the 2024 Israeli invasion, two Israeli tanks burst through the gates of a UNIFIL outpost on the border and ran over two peacekeepers, but the force could not return fire or succeed in punishing the Israeli soldiers responsible. If UNIFIL were to be disbanded, many Lebanese would lose even more faith in the international community’s peacekeeping abilities in their country. In its recent disarmament efforts within Palestinian refugee camps, the LAF has proved broadly ineffective in neutralizing the capabilities of the most militant factions, whereas UNIFIL has been far more successful vis-à-vis Hezbollah, though on a much more limited scale due to its manpower and resources. UNIFIL’s mission must not abandoned but strengthened, to support and build the capacity of the LAF, whether that be as force multipliers or advisors, allowing them to disarm Hezbollah more effectively, avoiding some of those issues it has recently encountered.

Conclusion

Hezbollah’s recent defeats and regional isolation, as well as the desire of the Lebanese public for civic peace, all mean that there has never been a more viable or urgent opening for its disarmament. To take advantage of this opportunity, the Lebanese government must exercise political and military caution, and it must prove to the Lebanese public that the LAF can defend the nation from aggression. Meanwhile, the international community must expand its efforts to support disarmament by continuing to aid the LAF and by expanding UNIFIL to reflect its vital importance in this delicate situation.

The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

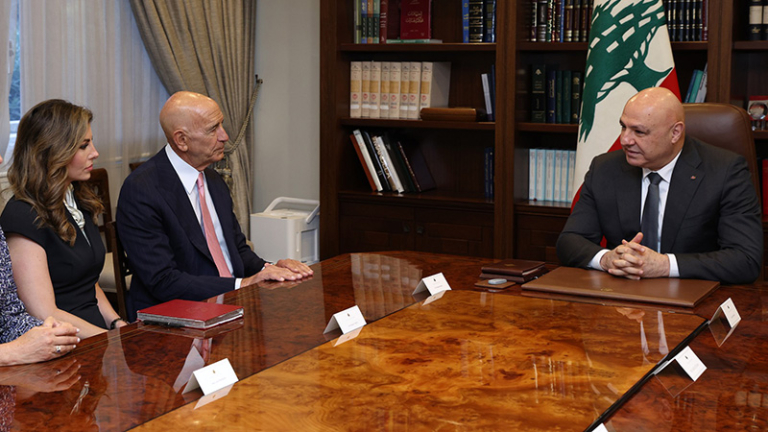

Featured image credit: FB/Lebanese Presidency