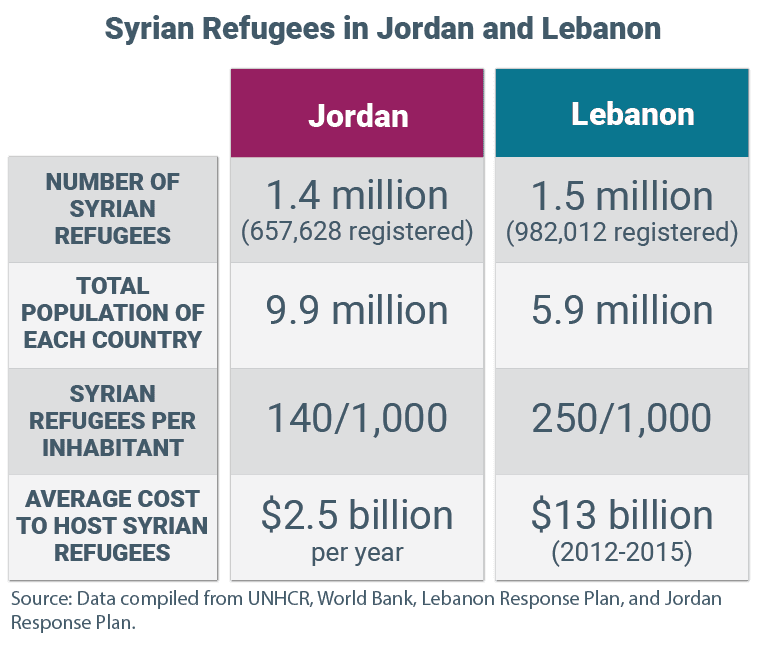

Overwhelmed by their own economic woes, Jordan and Lebanon are employing different tactics to achieve the same objective: to secure the return of Syrian refugees to their home country. This paper addresses the politics and policies driving the approach of both Amman and Beirut toward Syrian refugees and their potential return. The chart below offers a snapshot of the Syrian refugee situation in each country.

The Case of Lebanon: The Third Phase of Policy

The first wave of Syrian refugees arrived in Lebanon in April 2011. The arrival rate began to increase gradually as the civil uprising in Syria turned into an armed insurgency and a full-fledged civil war. Until mid-2014, three factors shaped the first phase of Lebanon’s policy toward Syrian refugees: 1) the weak cabinet of Prime Minister Najib Mikati, from June 2011 to February 2014, had a laissez-faire approach; 2) political and security tensions over the war in Syria between the two major rivals in Lebanese politics—the Iranian backed Hezbollah and the Saudi backed “Future” movement—had reached unprecedented levels and paralyzed governance; and 3) Washington pressured Beirut not to deny entry to Syrian refugees fleeing their war-torn country.

However, the political mood shifted in August 2014 when fighters from the so-called Islamic State (IS) and the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front kidnapped Lebanese soldiers and security forces in Arsal, a town on the Lebanese-Syrian border. Soon after, Hezbollah and the “Future” movement launched rounds of talks in December 2014, which paved the way for the second phase of security measures aiming to curb the flow of Syrian refugees. In October 2014, Lebanese authorities decided to stop welcoming displaced Syrians, barring exceptional cases, and asked the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to refrain from registering them. In January 2015, visa restrictions were introduced for Syrians entering Lebanon.

Additional factors shaped Lebanon’s policy toward Syrian refugees. The World Bank estimated that Lebanon had incurred losses of $13.1 billion between 2012 and 2015, reaching $5.65 billion in 2015 (11 percent of GDP). Public services, including infrastructure and social assistance, have become overstretched. The policy of Lebanese authorities is to forbid the establishment of refugee camps, arising from concern about repeating the Palestinian refugees’ scenario after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Instead, the displaced Syrians are now primarily spread throughout Lebanon’s most poverty-stricken communities.

There are numerous policy differences between Lebanese authorities and UNHCR that revolve around defining three terminologies: refugees, safe environment, and voluntary return.

After the laissez-faire approach in 2011-2014 and closing the border in 2015-2017, in early 2018 Lebanese authorities began the third phase of institutionalizing the return process of Syrian refugees. What paved the way for this phase was the control of western Qalamoun by Hezbollah and the Syrian regime, while the Lebanese military was in charge of its side of the border area in northeastern Lebanon. In his United Nations speech in September 2017, Lebanese President Michel Aoun launched a diplomatic campaign to return Syrian refugees to their country, noting that “it would be better if the United Nations assisted them in returning to their homeland rather than helping them remain in camps.” His speech raised arguments that became recurring contentious issues with international humanitarian actors working with Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

Indeed, there are numerous policy differences between Lebanese authorities and UNHCR that revolve around defining three terminologies: refugees, safe environment, and voluntary return. First, Lebanese authorities consider that their country is facing “mass influx” and label those who fled Syria as “temporarily displaced individuals.” The UNHCR, on the other hand, places them as part of a “refugee movement,” which means Syrian refugees are seeking international protection in a neighboring country. Second, there is a contrast in conflict assessment. Lebanese authorities believe Syria is stable enough for displaced Syrians to return, while the UNHCR argues the situation is not yet conducive for their repatriation. Third, there are differences in defining what constitutes “voluntary return” of displaced Syrians in Lebanon. Tensions grew in recent months when, in April, the Lebanese foreign ministry criticized the UNHCR’s questioning of hundreds of Syrian refugees to make sure their decision to return was voluntary. This was followed by a June 8 decision to freeze residency applications submitted by UNHCR staff. These squabbles appear to have been defused, but they are far from being resolved.

The Current Political Landscape in Lebanon

There is a recognition in Lebanese politics that the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad will remain in power for the foreseeable future. Legislative elections in May 2018 witnessed the comeback of the Syrian regime’s Lebanese allies to parliament. For now, the only Lebanese interlocutor with the Syrian regime on this issue is the general director of the Lebanese General Security, Major General Abbas Ibrahim, who is in regular contact with Lebanese officials, including the “national reconciliation” minister Ali Haidar and the concerned security agencies. One should not be surprised if, after forming a cabinet, Lebanese officials begin to engage Damascus on the ministerial level to discuss ways to increase cooperation on the return of Syrian refugees. To be sure, there are currently thousands of pending requests by displaced Syrians to return to their home country. While the role of Damascus is to provide security clearances as well as public transportation, the resource-stretched Assad regime is not delivering enough buses for the task—this seems to be one logistical obstacle to the return process.

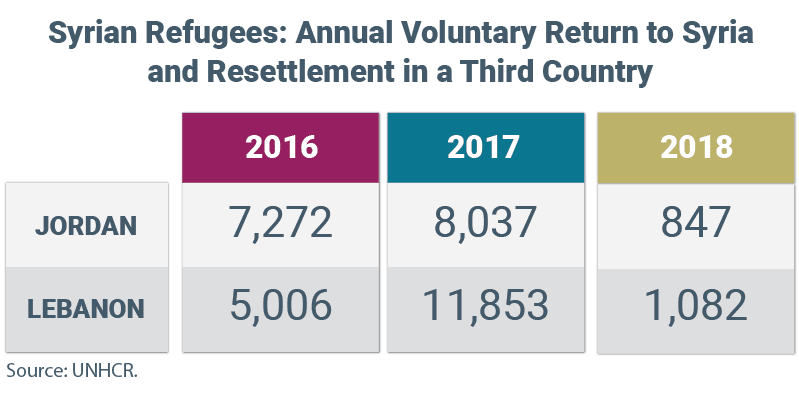

On the political level, Syrian refugees are in the Beqaa Valley, Baalbek, northern Lebanon, and the Beirut provinces, hence there is pressure from the constituencies (mostly in border areas) on Lebanese politicians to act. In the recent electoral campaign, candidates also played into their bases by heightening rhetoric against the Syrian refugees, and this was translated into policies by the Lebanese foreign ministry in the immediate post-election period. Prime Minister Saad Hariri had reservations regarding these unilateral measures against UNHCR, but he is either tacitly endorsing the return process or is unable to push back against a unanimous approach among Christian and Shia leaders. The low number of returnees in 2018 (1,082 so far) is expected to pick up in the coming months, most notably among refugees near the Syrian border.

The Case of Jordan: Awaiting Dynamics in Southwestern Syria

Since the early days of the unrest on its border, Jordan strived to remain neutral in the Syrian war, a decision meant to mitigate the threats emerging on its northern neighbor. Jordan’s policy toward the Syrian refugees went through three phases since 2011.

Phase 1, until mid-2013, was marked by a largely welcoming approach to Syrian refugees. The cross-border tribal connections between Jordanian host families and Syrian refugees fleeing southwestern Syria played a key role in Amman’s decision to keep the border open. In November 2011, King Abdullah became the first Arab leader to urge Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to step down. During this phase, Jordanian authorities gradually began to fathom the refugee crisis they were facing. Seventy-nine percent of registered Syrian refugees in Jordan (516,000) live in host communities in rural and urban areas, while the remaining 21 percent are in camps (Zaatari, Azraq, or Emirati Jordanian camp). The World Bank estimates that the Syrian refugees cost Jordan $2.5 billion per year (6 percent of GDP).

Phase 2 was defined by a security approach and the arming of the Free Syrian Army (FSA). Nearly 43 percent of the current number of Syrian refugees in Jordan arrived in 2013. However, this trend of Syrian refugees going into Jordan began to decrease dramatically in mid-2013 after a series of border measures were implemented, including closing all of Jordan’s western informal border crossings with Syria. This reflected the authorities’ mindset of perceiving the flow of Syrian refugees from a security angle. In April 2014, the Syrian Refugee Affairs Directorate was established, as part of Jordan’s security services, to police Syrian refugees and coordinate humanitarian aid. Jordanian authorities denied entry to Syrian men without relatives, Palestinian refugees from Syria, and undocumented persons and barred the entry to Queen Alia International Airport of all Syrians without Jordanian residency permits or special exceptions.

Jordan is on the verge of a turning point, a third phase that will largely depend on what happens in southwestern Syria.

The emergence of IS in mid-2014 and the killing of the Jordanian pilot Muath al-Kasasbeh in early 2015 reinforced the Jordanian security approach during the second phase. Amman decreased1 the number of crossing points of Syrian refugees from 45 in 2012 to 5 in 2015, including two camps dedicated for the refugees (al-Rukban and al-Hadlat, located near Jordanian military bases). Thousands of Syrian refugees became stranded in these informal crossing points. Jordanian authorities pointed out that it was not their responsibility to provide aid inside the al-Rukban camp.

Moreover, the deportation trend of Syrian refugees and strict border measures increased after two terrorist attacks near the Syrian border. A car bomb attack in June 2016 that killed six Jordanian soldiers and security officers near al-Rukban camp prompted Amman to declare the camp a demilitarized border zone cut in half inside both Jordanian and Syrian territory. The second attack came in December 2016 when gunmen killed 10 persons, including seven security forces, in the southern city of Karak. The strict border measures coincided with Jordan becoming the supply line of the US-led Military Operation Center in Amman, which equipped and trained the FSA troops operating in the Southern Front. However, Jordan closed its two official entry points with Syria once they came under the control of the armed opposition: the Daraa border crossing in October 2013 and the Nassib border crossing in April 2015.

This second phase was rather a readjustment to emerging dynamics and to three major developments: 1) the Russian intervention in Syria in September 2015; 2) the 2016 economic slowdown in Jordan, which led to restricting Syrian refugees’ access to the labor market; and 3) the July 2017 US-Russian ceasefire agreement in southwestern Syria, which closed the supply line via Jordan to the Southern Front.

Phase 3 opened possibilities. Jordan is on the verge of a turning point, a third phase that will largely depend on what happens in southwestern Syria where the Russian-backed Syrian regime recently launched an offensive. Jordan is expected to remain neutral and has sent tanks to the border. The best-case scenario for Jordan would be to open the border with Syria for trade and have the Syrian refugees return to their home country, while the worst-case scenario would be to face a confrontation between the regime and the armed opposition, with thousands of refugees stranded on the border waiting to flee the violence. Relations between Jordan and UNHCR have improved recently, after tensions in 2014-2016 when Amman implemented deportation measures. Moving forward, these relations might be tested once again. Jordan announced it will not take any refugees fleeing the current violence in southwestern Syria.

No matter what happens in the coming months, a large-scale return is unlikely in either Jordan or Lebanon.

Another factor involves Amman’s relations with Damascus. In May 2014, Jordan declared Syrian Ambassador Bahjat Suleiman a persona non grata, but the Syrian embassy in Amman remained open. Tensions grew between both sides after reports that Jordan might establish a buffer zone in southwestern Syria to return refugees to Daraa, but relations improved after the US-Russian ceasefire agreement last July. Amman did not cut diplomatic relations with Damascus and maintained2 that the Nasib border crossing will only open when it comes under the control of the Syrian regime. Moreover, there are indications that both sides are warming up to each other. A Jordanian trade delegation visited Damascus3 in May 2018 to discuss renewing trade between the two countries and reopening border crossings. So far, the channels to discuss the return of Syrian refugees have been the embassies in both capitals.

Similarities and Differences between Jordan and Lebanon

There are enough similarities between the attitudes and actions of Jordanian and Lebanese authorities. Both received a wave of Palestinian refugees (in 1948 and 1967), Iraqi refugees (2003), and Syrian refugees (2011), hence they share similar security, economic, and demographic concerns about refugees. Neither state is a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, which are the multilateral treaties defining who is a refugee and enumerating the rights of individuals seeking asylum.4

Moreover, Amman and Beirut reacted similarly to the rise of IS in mid-2014 by taking strict border measures. They are both currently restrained in their readiness to engage the Syrian regime. The number of Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon has stabilized since 2015 and can only decrease moving forward. Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon face a difficult choice between staying in a dire situation or risk returning to their home country; fully 87 percent of displaced Syrians in Lebanon have an accumulated average debt of $798, 76 percent are living below the poverty line, and 74 percent over 15 years old are without legal residency. However, the primary reason for refugees to return to their home country is family reunification. Both Lebanon and Jordan are following UNHCR recommendations and making some efforts to legalize the status of Syrian refugees in return for international aid pledges that are yet to materialize. Clearly, authorities in the two countries will have difficulty balancing public pressure at home to address the Syrian refugees with the recommendations of the international community.

Moreover, public debt has accumulated since 2011 in Lebanon ($80 billion) and Jordan ($38 billion). While the presence of Syrian refugees had a positive impact on the local economy in Jordan and Lebanon, it has also constrained public services. Both authorities are using the serious challenges posed by Syrian refugees as a scapegoat to delay the needed structural economic and fiscal reforms.

Lebanon is ahead of the curve in the process of returning Syrian refugees because the question of who controls the border area has been resolved; but there are logistical and political challenges ahead. Jordan could either face a new refugee crisis or see a swift return of refugees if the outcome in southwestern Syria serves Jordanian interests. No matter what happens in the coming months, a large-scale return is unlikely in either Jordan or Lebanon. The return process will not be completed overnight and will take years.

ACW intern Sarah Jamesen contributed to this policy paper.

1 Source is in Arabic.

2 Source is in Arabic.

3 Source is in Arabic.

4 Jordan signed a memorandum of understanding on these issues with UNHCR in 1998.