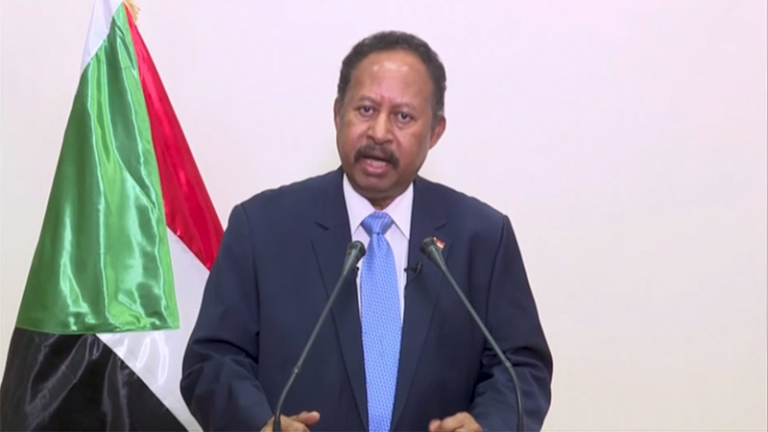

In a move that reflected his failure to garner the support of the Sudanese public, Sudan’s Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok submitted his resignation on January 2nd. Lamenting the end of his mission to form a cabinet that he thought would assure unity and social peace, Hamdok warned that his country “is crossing a dangerous turning point that threatens its whole survival.” But his ruefulness will not save the day, for his example may stand as yet another case of a political leader who sacrificed his popular legitimacy and reputation at the altar of the interests and machinations of the military institution that, only ten weeks ago, toppled him and put him under house arrest.

That Hamdok failed to put into effect the November 21, 2021 agreement with his military captors was arguably a foregone conclusion. To be sure, he was rumored to have been on the verge of resignation twice before, on December 21 and December 27, all for the same reason: the inability to find civilians to cooperate with him without losing street support. When he accepted to be released from house arrest in November and was designated again a premier of a sought-after technocratic cabinet beholden to the military, he in effect forfeited a popular legitimacy gained as a trusted and capable civilian technocrat to lead the government of the post-2019 constitutional declaration, one that supposedly began Sudan’s transition to democracy and civilian rule.

Sudan today continues on its downward spiral toward possible civic disorder after months of political instability. Hamdok’s resignation highlights a set of domestic and external conditions to be addressed immediately. First, there must be a quick and unmistakable return to civilian rule as was planned by the constitutional declaration. Civilians were to take over leading the Sovereignty Council just a few weeks after then-president of the council, General Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan, staged his putsch on October 25, arrested Hamdok and other civilian leaders, suspended the 2019 declaration, and announced a new transition plan. It was indeed strange that Hamdok agreed to work with Burhan again in November, knowing that the military could not be trusted with planning a process for a transition to civilian rule.

Second, the Sudanese military must fully withdraw from politics and return to the barracks. If the 2018-2019 revolution against former dictator Omar al-Bashir signified anything in the country after his three decades in power, it is that the Sudanese no longer saw the military institution as a credible governor or a guarantor of civic peace and tranquility. While not in power for as long as Bashir, Burhan and his co-generals are no different from their old mentor. And just as Bashir toppled a nascent democracy in 1989 to establish his authoritarian rule, Burhan and his comrades staged the October 25 coup in order to scuttle Sudan’s transition to civilian rule and the start of consolidating democratic institutions. Today, the urgent task is thus to coalesce domestic and external pressure to force the military to accept that it is solely a security organization that must abide by civilian democratic rule and politics.

Third, it is imperative that the forces of civilian opposition to the November 21 Hamdok-military agreement start a serious and purposeful national dialogue on a program of reform. Such reform should not be limited to building the political façade of a democratic state—charters, elections, state institutions, and the like—but it must also expand to building the foundations of a successful economy that improves the lot of the majority of Sudanese. At the same time, it is essential that such a dialogue include all political forces interested in a democratic polity as well as all productive sectors and stewards of the economy. Much is at stake in a successful economic rebound that could reward the public agitation in Sudan’s streets, reliant as it is on an aspiring youth movement.

Fourth, Sudan needs the cooperation of regional and international actors that are currently involved, either positively or negatively, in its affairs. Most importantly, the Sudanese armed forces must withdraw their troops from Yemen where they provide assistance in defending Saudi Arabia against attacks by insurgent Houthis. Recently, 14 Sudanese soldiers were killed in an attack by the Houthis at the northern Yemeni border. While deploying such soldiers may be seen as a form of rent-seeking for a poor country, the practice has the undesirable impact of involving Sudan in a war it does not control. Direct interference by Egypt and Saudi Arabia in Sudan, on the side of the military, must also be stopped because it stands squarely against the wishes of the Sudanese people. As for the United States, declarations about rejecting the military coup and a return to civilian rule are encouraging signs that the Biden Administration is finally standing by its rhetoric in support of democracy and human rights. Moreover, Washington must put additional pressure on the military institution to avoid bloodshed in its illegal suppression of street protests, and to indeed withdraw from the public square.

After the constitutional declaration of 2019, Sudan was cautiously and optimistically moving toward planning a democratic transition and a process of de-escalation from the repression of the Bashir regime, albeit under military supervision. Now that the military has shown its true intentions and those who thought they could cooperate with it have failed to produce what the Sudanese people desire, it is high time to allow the revolution against Bashir to continue its course. Two camps must now take decisive action: the military must cede its failed role as steward of the transition and return to the barracks, and the civilian opposition must rise to the occasion of forging a working formula to move forward. No more bloodshed is needed—it never was—on Sudan’s path toward a civilian and democratic form of government for everyone.