On October 25, 2021, Sudan’s General Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan staged a coup, declared a state of emergency, dissolved the power-sharing Sovereign Council, sacked the civilian government, and temporarily detained Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and his ministerial team as well as other activists and political figures. While the international community has responded swiftly and rejected the coup and pushed for the return of the civilian government and the immediate release of the detainees, regional responses were unclear, reactionary, and in some cases supportive of the coup. This exposed the complexity of the situation in Sudan and the impact of regional dynamics on the country’s political transition.

A Coup in the Making

Military coups are not uncommon in Sudan’s history. The country, like many others in Africa and the Arab world, has been under military rule for decades and has not had a civilian government since the late eighties, when General Omar al-Bashir carried out a military coup and toppled an elected government in 1989. He stayed in power until he was removed by a popular uprising in 2019. Sudan then came under a transitional arrangement through a partnership between military and civilian leaders who signed a power-sharing agreement in August 2019. However, owing to its institutional capacity and influence, the military has become the de facto ruler of Sudan with no real power in the hands of the civilian government. The Sudanese military, led by Burhan and his deputy, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti), seems keen to remain in power at the expense of civilian leaders who are represented by Hamdok and his allies in the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition. Thus, since Burhan became the president of the Sovereignty Council, he marginalized the role of Hamdok’s government, internally and externally, to the extent that some observers consider it a mere subordinate to the military.

Since Burhan became the president of the Sovereignty Council, he marginalized the role of Hamdok’s government, internally and externally.

In addition, there was a growing feeling among the FFC that the Sudanese junta would not relinquish power to civilians. It is noteworthy that Burhan’s coup came just one month before the date set for handing over the leadership of the Sovereignty Council in November. However, the coup would not have been possible without several factors such as the growing disagreements and tensions within the FFC on how to deal with the military and the timeline for transferring power to civilians. These tensions resulted in weakening the civilian bloc and led to significant splits within the FFC. In fact, one day before the coup, the FFC warned of what it dubbed a “creeping coup,” which reflects the growing gulf of mistrust between the coalition and the military. Also, Burhan took advantage of the public resentment against Hamdok’s government and the protests that took place a few days before the coup because of the deteriorating social and economic conditions. Finally, Burhan exploited the failed coup attempt led by officers within the Sudanese armored divisions on September 21, 2021, which fueled the already existing fears of an actual coup that occurred later on October 25.

A Regional Axis of Counterrevolution

The uprisings of the so-called Arab Spring have been facing a fierce regional counterrevolution that seeks to undermine and abort any democratic transition in the Arab world. Led mainly by the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, this axis of counterrevolution firmly believes that democracy is an existential threat that jeopardizes their rule and can lead to chaos and instability. For them, any calls for political change in the region should be countered and eliminated at any cost. Over the past decade, these countries have been heavily involved in the political conflicts across the region, from Yemen to Syria and from Egypt to Tunisia. They use their political, economic, financial, and diplomatic clout in order to influence the dynamics of the domestic uprisings and shape their outcome.

Led mainly by the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, this axis of counterrevolution firmly believes that democracy is an existential threat that jeopardizes their rule and can lead to chaos and instability.

The current wave of the counterrevolution began in Egypt in the summer of 2013 when it succeeded in unseating the late President Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first freely and democratically elected president. By pouring billions of dollars into Egypt’s ailing and fragile economy, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait could reverse the tide of the Arab Spring and help install then-Army Chief Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi to become Egypt’s new ruler. Since then, the entire dynamics of the region have shifted. Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad remained in power and is slaughtering and displacing millions of Syrians internally and externally. Libya and Yemen slid into a destructive civil war with the military, financial, and political involvement of the trio of the counterrevolution: UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. And finally, a slow-motion coup halted Tunisia’s democratic transition and put an end to the only success story of the Arab Spring.

Therefore, it is not surprising that these three countries, along with Israel, have been involved in varying degrees in the ongoing political crisis in Sudan. In fact, some of them played a key role in supporting the Burhan coup and provided him political and diplomatic support to counter and mitigate international pressure.

Egypt’s High Stakes in Sudan

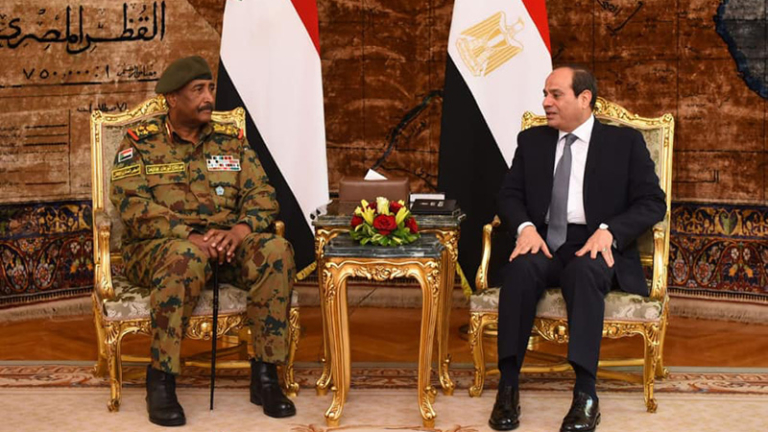

Egypt’s response to Burhan’s coup reveals the extent to which regional players can impact the political situation in Sudan. Egypt has neither condemned the coup nor called for the return of the civilian government; in fact, it played a key role in encouraging and supporting it. A few hours after the coup, Egypt’s foreign ministry issued a short statement on its Facebook page calling on all Sudanese parties to exercise “self-restraint and prioritize Sudan’s high interest.” More importantly, while Egypt’s regional allies—Saudi Arabia and UAE—called for the return of the civilian government, Egypt blatantly asked Burhan to dismiss Hamdok. According to the Wall Street Journal (WSJ), Abbas Kamel, the chief of Egypt’s General Intelligence Service, Khartoum before the coup where he met with Burhan and told him: “Hamdok must leave.” Furthermore, according to the same report, Burhan secretly visited Cairo one night before the coup and met with Sisi to secure his political support for the coup. After the coup, Egypt worked tirelessly to form a regional lobby that could provide political and diplomatic support to Burhan and to assuage the mounting international pressure on him to end the coup and reinstate Hamdok. Burhan finally had to comply under a new political agreement signed with Hamdok on November 21.

The question of why Egypt supports Burhan’s coup is paramount and helps explain Cairo’s position on the current crisis in Sudan. First, Egypt has no interest in civilian rule, let alone a democratic one, in Sudan. Sisi’s regime, which itself came to power through a military coup in 2013, will not allow any democratic transition to unfold on Egypt’s southern or western borders with Libya. For Sisi, this is an existential threat that cannot be accepted or tolerated. Since the toppling of Bashir in 2019, Sisi has been keen to prevent civilians from taking over the country and provided political and diplomatic support to the Sudanese junta.

Second, Khartoum falls within the parameters of Cairo’s national security because Egypt views Sudan as part of its geostrategic depth and its only gate to Africa. Therefore, it is crucial for Egypt to have a collaborative—if not submissive—government in Sudan where it can exert influence and guarantee full support. Importantly, only the Sudanese military is able to provide Cairo with such political leverage since any civilian-elected government would not allow Sudan to become a mere puppet of Egypt.

It is crucial for Egypt to have a collaborative—if not submissive—government in Sudan where it can exert influence and guarantee full support.

Third, the issue of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) is vital for Egypt and it cannot be resolved without securing Sudan’s full and unequivocal support. According to the WSJ’s report, Egypt was displeased with Hamdok’s position on GERD “because of his openness to Ethiopia.” The GERD issue is critical for Sisi’s regime stability and legitimacy as Egyptians blame Sisi for jeopardizing Egypt’s water security after signing the Declaration of Principles with Ethiopia and Sudan in March 2015. In addition, Egypt’s military has developed strong relations with its Sudanese counterpart over the past two years, which could strengthen Egypt’s position vis-à-vis Ethiopia. Therefore, Egypt counts on Sudan’s unequivocal support on the GERD issue, one that can be guaranteed only under a military rule.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia

In the past, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have invested heavily in Sudan both during the era of former President Omar al-Bashir and after his removal from office in 2019. In 2015, Bashir joined the Arab Coalition forces and provided military support to the Saudi-led war in Yemen. After he left office, Emirati and Saudi support to the Sudanese junta not only continued but increased significantly. Noticeably, Abu Dhabi and Riyadh have developed a special and strong relationship with Burhan and Hemedti, providing them with massive political, financial, economic, and diplomatic support in order to secure their loyalty and subordination. Therefore, when Burhan staged his coup on October 25, both countries had similar responses but did not clearly condemn the coup. They followed Egypt and called on Sudanese parties to practice self-restraint and de-escalation.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia believe that a civilian government in Sudan might result in losing Sudanese political and military support not only for the war in Yemen but elsewhere in the region.

Clearly, the UAE and Saudi Arabia would not like to see moves toward democratic rule in Sudan. This is because they, along with Egypt, represent anti-democratic forces; in order to protect their strategic interests in the region, they must fully control the regime in Khartoum. The UAE and Saudi Arabia believe that a civilian government in Sudan might result in losing Sudanese political and military support not only for the war in Yemen but elsewhere in the region—and particularly in Libya, where both countries are involved and support the warlord Khalifa Haftar. Furthermore, losing Sudan means missing a strategic advantage in the Horn of Africa where both countries, along with Israel and Egypt, are attempting to exert control. Abu Dhabi and Riyadh are also wary that an elected government in Sudan might shift gears in its policy toward other regional players such as Turkey, Qatar, or Iran, and this could affect their interests. Finally, both countries, along with Egypt, are aware of the growing public sentiment among Arab youth, particularly in Sudan, against counterrevolutionary policies in the region; they believe that only the military can suppress this sentiment and prevent its spread across the region.

Israel’s Fear of Losing Sudan

Since the removal of Bashir from office, Israel has tried to develop special relations with the Sudanese junta, which became the de facto ruler of the country. Using its political leverage with the Trump Administration along with the financial clout of the UAE, Israel succeeded in dragging down Sudan to join the list of Arab countries that normalized ties with it. Therefore, during the past two years, Israeli officials have developed a special relationship with Burhan and Hemedti, both of whom seem to be enthusiastic about normalization with Israel in exchange for political and economic gain. Since Burhan’s coup, Israel has been closely monitoring the situation in Sudan with hopes it would not affect the normalization process between the two countries. Despite the announcement of normalizing relations between Khartoum and Tel Aviv, an official agreement is yet to be approved and signed by them. Not surprisingly, an Israeli delegation that included members of the Mossad intelligence service visited Khartoum a few days after the coup in order to assess the situation and to make sure it would not affect the normalization process. Moreover, the United States asked Israel to use its ties with Burhan to end the coup, a sign of how much influence Israel has over the Sudanese junta. Clearly, Israel fears that the Burhan coup could harm, or at least slow down, its normalization ambitions either with Khartoum or with other Arab countries.

Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan’s coup reveals the complexity of regional dynamics in the Middle East and North Africa and the ways they impact the situation in Sudan. It is also another testament to the fact that the Arab Spring remains a key threat to authoritarian regimes in the region and their allies, who continue to stand ready to do whatever is necessary to stop nascent moves toward political change and democratization.