On May 15, 2018, Palestinians commemorate 70 years of their Nakba, the catastrophe of dispossession and homelessness that unfolded when the state of Israel was established and hundreds of thousands were expelled from historic Palestine to become refugees in neighboring countries. Confronting their current situation and rectifying the mistakes their leadership has made since that time are challenging hurdles that Palestinians must overcome to effectively bring the Nakba to an end. A united Palestinian front that speaks to all segments of Palestinian society is the only path toward viably challenging the policies of a significantly stronger Israeli state.

The Nakba’s Start

In the spring of 1948, as the British mandate of Palestine was ending, a decision by the United States to reconsider its position on the so-called United Nations Partition Plan (Resolution 181 of November 1947) was causing anxiety among Zionist leaders on the ground. In effect, Washington was practically backing out of a commitment to establish a Jewish state in Palestine. Zionist leaders thus decided to shift the fight from communal attacks to full blown conquest operations of Palestinian lands. Their aim was not simply to defend territory where the Jewish population lived, but to acquire and hold territory by conquering Palestinian populations and the villages and towns in which they lived.

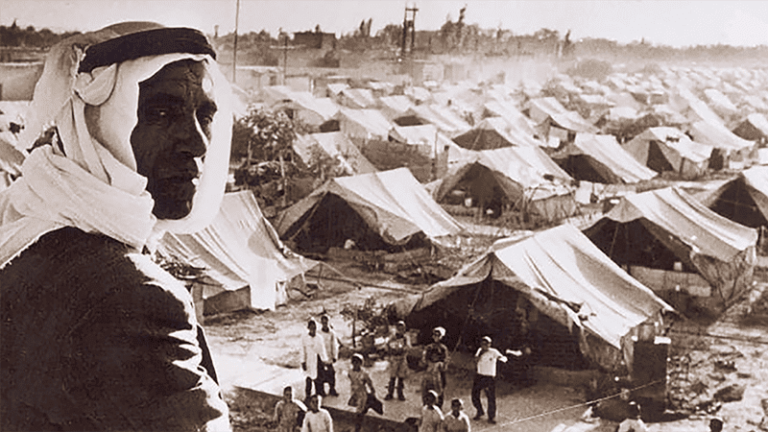

From November 1947 through May 14, 1948, 250,000-350,000 Palestinians became refugees, many streaming into Jordan and Lebanon, after Zionist militias depopulated the largest Palestinian population centers. All of this took place prior to the declaration of the Israeli state and the subsequent entry of Arab national armies into Palestine the following day. By the time the final armistice agreement was signed in 1949, at least 750,000 Palestinians had become refugees, with approximately 530 Palestinian towns and villages depopulated by Zionist forces.

Making Ethnic Cleansing Permanent

After this period, the Israeli state issued a series of measures aimed at making permanent the new demographic reality on the ground. Palestinian refugees who attempted to return to their homes in the early years after 1948 were often shot as the military was charged with preventing them from returning. In these formative years of the Israeli state, hundreds of Palestinian villages were razed as part of a policy of preventing refugee return. It was also during this period that the Israeli state began to promulgate laws aimed not only at cementing the demographic inversion created by the war but also at confiscating properties of the refugees who were denied return.

Some of these state decrees included laws on citizenship and nationality as well as the “law of return,” which permitted Jews living anywhere in the world to immigrate and become citizens of the new Israeli state. In contrast, other laws defined as “infiltrators” those who had resided in the land but had become refugees. Thus, by facilitating the in-migration of Jews from around the world and preventing the return of non-Jewish residents, the Israeli state affirmed its intention to structure the country’s demographics in a very specific and discriminatory way.

Once it became clear that Palestinian refugees would be denied return, new laws were created to confiscate their property. Land laws determined that “absentees”—people who were not present on the land to claim their property—would have their land confiscated by the Custodian of Absentee Property, who would then dispense of it in a way that suited Jewish interests. The fact that the state itself was ensuring that these “absentees” were absent only because the state was denying them return did not prevent what became a land laundering system for effectively seizing the vast majority of the land. It was at this formative stage of the state and its relationship with the Palestinians that the principle of taking Palestinian geography without Palestinian demography, and using legalistic maneuvers to do it, was consolidated. That is not, of course, where it ended.

The Continuing Nakba

The process of expropriating Palestinian land did not stop after 1948. What followed over time, both inside the new Israeli state and in territory it would later occupy in 1967, was an extension of this very same process across time and space. For example, demonstrations by Palestinian residents of Sakhnin and Arrabeh, in present-day Israel, against Israeli land confiscation in 1976 were met with brutal force as Israeli officers shot and killed several demonstrators; Palestinians called this seminal event Land Day. Of course, in territory Israel occupied in 1967, its policies took a similar though expanded form, building illegal settlements in areas deemed closed military zones.

As this process accelerated over time, it led to the current situation where Israeli settlements dot the entire West Bank and dominate the hilltops as well as the land, water, and mineral resources that surround Palestinian villages. Together with the civilian as well as military infrastructure that comes with them, which are routinely off limits to Palestinians, the matrix of settlements creates a vise-grip on Palestinian life in the West Bank and in East Jerusalem. From Gaza to Jerusalem to the southern Naqab desert region, where Palestinian Bedouin citizens of Israel are being forced from their land, the blueprint has been the same since 1948: take the land, expel Palestinians and concentrate them elsewhere, and use brute force to quell resistance to the project.

Gaza’s Message

For the last several weeks, Palestinians in Gaza have been participating in weekly protests, risking their lives before Israeli military snipers who have orders to shoot. Dozens have been killed so far and 5,511 injured. The dismal humanitarian conditions in the besieged Gaza Strip are well known; for Palestinians who have been living in Gaza under a tightened siege for over a decade now, it is easy to understand how they might feel that the world—or that other Muslims, Arabs, and even Palestinians—have forgotten them. Thus, it would have been entirely understandable if the protests in Gaza focused solely on the unique plight of Palestinians there, demanding an end to the siege, access to the sea, and free movement outside the Strip’s open-air prison.

That was not the approach the protest organizers chose, however. Instead, the protesters chose to put forward a pan-Palestinian message. They started their protest on Land Day on March 30, and they aim to continue their protests until May 15, the date Palestinians mark as the beginning of the ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Under a Palestinian flag and calling for a right of return for refugees, the key message from the Gaza protests is a single demand of unity. This message, being delivered on the 70th anniversary of the start of the Nakba, has never been more timely and important.

Ending the Nakba?

For years, Palestinian aspirations have centered around ending the Nakba that began in 1948 and continues in various forms. During this struggle, a strategic shift on the part of the Palestinian leadership led Palestinians into a “peace process” that was mediated by Washington, with the ostensible aim of producing an independent and sovereign Palestinian state. Often described as “pragmatic,” this approach has actually weakened the Palestinian national movement dramatically: it was seen by many as inherently relinquishing the interests and claims of the Palestinian diaspora, refugee communities, and Palestinian citizens of Israel. The result has been the fragmentation of the Palestinian national movement precisely at the moment when Israel was becoming stronger.

On April 29, 2018, the Palestine National Council, the highest body of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), began its 23rd ordinary meeting to confront a variety of issues that needed urgent attention. The leaders of the PLO, including the chairman, Mahmoud Abbas, are older, out of touch with the vast majority of their populations, and desperately lack legitimacy. Among Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, approximately 70 percent want Mahmoud Abbas to resign—and this is the segment of the Palestinian population where he can potentially claim the most legitimacy.

Even this effort, however, was tainted. Based in Ramallah, where Palestinians in Gaza and many elsewhere are unable to attend, the convening was structured to effectively lean in one direction. Political movements spanning from the Islamist Hamas and the traditionally Marxist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine boycotted the event. Once again, a Palestinian event that could have presented an opportunity to create legitimacy was doomed to merely reshuffle the leadership of one primary faction, Fatah.

Ending the 70-year Nakba will require Palestinians to think outside the box of the long-running and virtually moribund peace process that has constricted their political movement and trapped them in an unending cycle. Protesters in Gaza sent a message to the world, but they are speaking to all Palestinians as well. The question remains as to whether the Palestinians who needed to hear their message are actually listening.