Almost four years into President Kais Saied’s imposition of one-man-rule in Tunisia, his effort pivots around a process of “executive aggrandizement” that is designed, among other things, to subordinate the judiciary to the president. Saied began this judicial power grab in February 2022 by purging judges and reorganizing the judiciary. His efforts were bolstered by popular disillusionment with the political elite and by generational, personal, and ideological tensions in the judicial community. His assault also benefited from disputes between and within Islamist and secular parties over appointing a constitutional court that would have the right to judicial review and even conditional authority to impeach the president. Seeking to weaken any such body, in 2022 he replaced Tunisia’s 2014 democratic constitution with a new one that, among other problems, stipulated that the president appoints the high court’s judges. Saied’s move was not surprising. A former professor of constitutional law, Saied wrote the constitution’s most authoritarian articles. Henceforth, he was well positioned to use the courts as a tool of repression without fear of repercussions.

The good news, if there is any, is that some judges and prosecutors have resisted Saied. But others are enabling him, some out of loyalty, but most out of fear that unless they convict his critics every time the president concocts a conspiracy, they will be declared “enemies of the state.” Aware of the fate that befell some of their colleagues, Tunisian judges must sometimes choose between doing Saied’s bidding or tasting the arbitrary justice that they themselves have dispensed.

Kais Saied Wants to Make Tunisia Great Again

The dilemmas facing judges in Saied’s Tunisia are illustrated by the battle that erupted after a court on April 19, 2025 sentenced 40 people to prison for terms of up to 66 years. The list of the condemned—12 of whom were outside Tunisia and thus beyond reach—is a Who’s Who of the elite of lawyers, politicians, human rights activists, and entrepreneurs who flourished in the previous decade of Tunisia’s genuine, if wobbly, democracy. In a Kafkaesque “judicial process,” these men and women were charged not only with “conspiracy against the internal and external security of the State,” but also with a so-called crime that was as novel as it was vast: trying to “change the nature of the state.” In February 2024, a financial court sentenced former Speaker of the Tunisian Parliament and leader of the opposition Islamist Ennahda Party Rached Ghannouchi to three years in prison over accusations of receiving foreign contributions.

Saied is convinced that he is the sole interpreter of the people’s will.

This second vague charge telegraphed the fundamental issue at stake for Saied. He is convinced that he is the sole interpreter of the people’s will and thus that state and governing institutions belong only to him. Therefore, he sees any effort to defy his self-proclaimed ownership rights as an attack on the state itself. The most dangerous source of any such assault comes from a cross-ideological alliance of leaders—secular, Islamist, liberal, or socialist—that tries to defend the rule of law or the principle that parliament and especially the judiciary should check the power of the president. The charge of a vast conspiracy aims at crippling or preventing the emergence of any such alliance.

Saied, it should be noted, is not (so far) seeking to physically eliminate his imagined enemies (a step that would provoke an outcry and that is very unlikely given a 20-year moratorium on the death penalty in Tunisia). But he is trying to portray them as an alien political species, one that, as French scholar Vincent Geisser puts it, “incarnates…a conception of a Tunisian open to the multicultural world.” Saied’s insinuation of foreign contamination goes hand and hand with his assertion that the thousands of African migrants who came to Tunisia in the past decade are a dangerous “horde” funded by foreign powers as part of a “criminal plan to change the composition of the demographic landscape in Tunisia.” Using the whips of xenophobic nationalism, identity politics, and race baiting, it might be said that Saied is trying to “Make Tunisia Great Again” by tying any internal forces that he believes are undermining his rule to alleged foreign meddling.

Spring 2025 and the “Conspiracy” Cases

The accusation helps to explain the charges of prosecutors leveled in spring 2025 of a vast “conspiracy” (mu’amara) involving meetings of two groups of Tunisian political figures, one in Belgium and another in Tunisia. Some of these meetings did occur, but there is no evidence that the Tunisians who attended them were doing anything other than exercising their rights to free speech and association.

To appreciate the wider “logic” (or illogic) of the charges, consider the case of Khayam Turki, one of the key targets of the “conspiracy” indictment. A prominent liberal political leader since 2015, after Saied’s 2021 auto-golpe Turki hosted leaders from the various political camps at his home. Moreover, in April 2022 he allegedly met with a US Embassy Tunis political officer. In Saied’s imagination, Turki violated two inviolate red lines: he allegedly tried to topple the regime by forging a dialogue across the ideological divide, and did so in league with the United States. Seeking to assign nefarious purpose to the embassy meeting, prosecutors noted that in addition to the US political officer there were two other “officers,” one of whom, it was later learned, was a translator and the other a note keeper.

Saied is trying to tie any internal forces that he believes are undermining his rule to alleged foreign meddling.

To emphasize the idea of a foreign plot, prosecutors also claimed that the French intellectual Bernard-Henri Levy—whom prosecutors described as nothing less than the “the godfather of coups d’etat in the world”—and Vice-President of the World Jewish Congress Pierre Besnainou (himself of Tunisian birth) were involved. The assertion, one analyst writes, was “icing on the cake,” since, after all, what is a good conspiracy theory if it does not include a “necessary Zionist” or two? For his supposed sins, Levy was sentenced in absentia to 33 years.

The April 19, 2025, trial lasted less than a minute and was conducted without the presence of the accused, who for “security purposes” were allowed to watch from their cells via video (at least those imprisoned in Tunisia). The judges proclaimed the defendants guilty after many lawyers and visiting judges stormed out of the courtroom, protesting verdicts that they knew were a forgone conclusion, as leading human rights groups noted in separate statements and in a joint condemnation signed by 39 organizations. For these imagined crimes of talking with representatives of the embassy of a close foreign ally, Turki was sentenced to 48 years in prison.

Following this show trial, on June 20, 2025, a special “terrorism” court sentenced Moncef Marzouki—post-revolutionary Tunisia’s first president and the country’s first freely elected head of state—to 22 years in prison in absentia. (Seventy-nine-year-old Marzouki had fled to France after Saied’s coup, and was deemed an ‘enemy of Tunisia.”) The fate of Marzouki, who is unlikely to be able to return to Tunisia during the remaining years of his life, signals Saied’s resolve to silence political leaders from the 2011-2021 post-revolution period, and even more so, to signal that anyone defying Saied will suffer the same judicial fate of those convicted on April 19.

Judge Ahmed Souab’s Arrest Sparks Protests

Just a few days later, authorities arrested former administrative court judge Ahmed Souab on security charges. An outspoken firebrand and thorn in the government’s side, he had defended two defendants in the conspiracy cases, Ghazi Chaouachi and Ridha Belhaj. Beyond Souab’s assertion that the entire trial was a “farce,” what especially angered prosecutors was his claim, made a day before the verdict, that “knives are at the throats of not just the detainees but also the president of the judicial department about to make the ruling.” By daring to suggest that the presiding judge was as much a victim of state pressure as the defendants, Souab highlighted the fear-based nature of the justice system under Saied. Faced by his damning assertion, the state retaliated by levying terrorism-related charges against him.

This crass distortion fooled no one, as a video of the statement Souab had made standing on the steps of the court building, in the presence of many of his fellow judges and lawyers, was posted on Facebook. Angered as much by the state’s clumsy manipulation of his words as by the arrest itself, protestors assembled in downtown Tunis to demand Souab’s release. Over several days in late April and early May, the demonstrations grew, as several thousand protestors, including relatives and friends of the accused, protested the verdicts. Thus it seemed that the conspiracy trial and the government’s arrest of Souab sparked a wider mobilization of urban professionals, university students, and social activists against the president’s judicial assault. Several private online news outlets also echoed these protests, including Business News and The Kapitalist (both of which, as indicated by their names, have ties to the business community).

Saied’s Regime is Probably Not on the Path to “Auto-destruction”

This was not the first time that such protests have erupted in Saied’s Tunisia, and it is unlikely to be the last. Indeed, demonstrations have occurred over the last two years, most notably before and after Saied’s staged “reelection” in 2024, a vote that was held after the regime cracked down on the opposition. Protests also broke out after the arrests of those who were sentenced in the April 2025 trial. But the potential political significance of these protests hinges on three factors: a sustained momentum that mobilizes a wider swath of the urban middle, professional, labor and business sectors; a process of elite defection from within the regime itself, sparked by mass protest; and a readiness of the security forces to refrain from using deadly force against demonstrators. In, short, the protests must have the space and opportunity to spark what scholars have called a “cracking of the state.”

The prevailing mood is one of both apathy and anger, but also of little appetite to reinvent the dynamic that led to the 2011 “Jasmine Revolution.”

It seemed for a long moment that the spring 2025 protests might open the door to such a dynamic. That on April 20, 2025, some 45 leading university professors from faculties of law and political science signed a document denouncing the trial and the judges who presided over it hinted at the chances of a wider movement. The readiness of these professors, part of a huge public university sector whose members have a lot to lose not only in terms of salaries (which are modest) but more so in terms of status, to denounce the regime represents a challenge for the state itself of which they are a part.

Yet while some Tunisian analysts argue that Tunisia has been “seized by the rage of auto-destruction,” that conclusion seems premature. Thus far there is little evidence of a wider mass movement or significant defections within the judiciary or the security sector. Although any sudden event could change the equation of forces sustaining the status quo, the prevailing mood is one of both apathy and anger, but also of little appetite to reinvent the kind of dynamic that led to the 2011 “Jasmine Revolution.” With political leaders who have little traction with the wider populace in prison, and having retaliated against a judge who had the audacity to highlight the very potential of defection within the judiciary, Saied has little cause for concern.

Regional and Global Politics Favor Saied

The global and regional equation is also playing to Saied’s favor. Every day the Tunisian state-owned or dominated media is flush with horrific images of the Gaza war and Israel’s assault on Palestinian civilians, providing a useful if deeply disturbing distraction from Tunisian domestic realities. The US-Israel-Iran conflict plays a similar role, although it does not get quite the same amount of attention in Tunisia. Moreover, the glory days of Tunisia as a competitive democracy following the 2011 political uprisings have been forgotten on the international stage. The country plays little role in the geostrategic calculations of its neighbors or of regional and global powers.

Western countries that could, in theory, exert limited influence over Tunisia are dominated by political leaders who want to limit the impact of African migration from and through Tunisia to their own countries. This includes French President Emmanuel Macron and many of his European Union allies. Indeed, while the Biden administration raised (very occasional and mild) questions about the human rights situation in Tunisia, US President Donald Trump has advanced his own process of executive aggrandizement while dismembering the US government infrastructure of human rights and promotion and democracy aid abroad. A look at the Facebook page of the US Embassy in Tunisia shows its focus on sports, tourism, and other non-controversial issues. There is no hint of anything to do with Said’s authoritarian project, nor has the American ambassador or any other embassy official assailed Said’s authoritarian project, which is perhaps understandable given that he has used nationalist language against foreign powers to deflect assaults on Tunisia’s “sovereignty,” even as he has sustained decent relations with the United States.

How long Saied’s authoritarian project will endure is anybody’s guess. But a counter project to revive and re-define democracy and pluralist politics will be the work of a generation, which apart from finding new leaders must also bridge the identity divides that undermined Tunisia’s post-2011 decade of democratic experimentation. This is likely to take decades of struggle under the shadow of a repressive government, and with the looming possibility that a widening social crisis could spark a move in the security apparatus to seize power if Saied seems unable to respond to the challenge.

The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

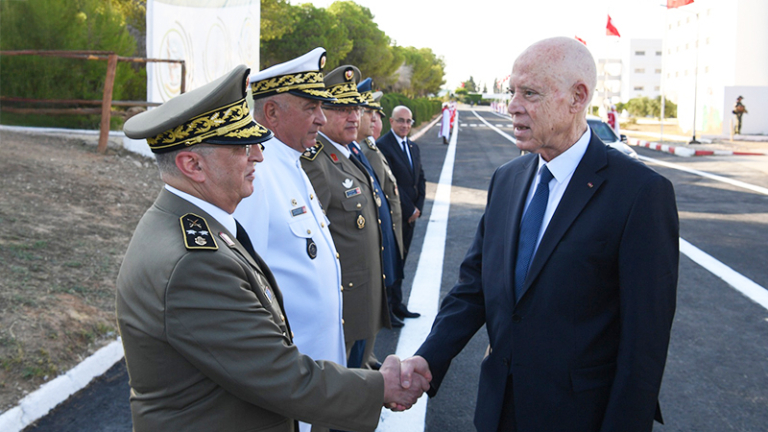

Featured image credit: FB/Présidence Tunisie