With Tunisia’s slide into autocracy accelerating every day, this hardly seems the best moment to undertake a frank assessment of its democratic experiment. To be clear, President Kais Saied bears the primary responsibility for breaking Tunisia’s young democracy. But a postmortem of the factors that helped set the stage for his July 25, 2021 self-coup is still necessary. After all, what Saied has done—with the backing of conspiracy peddlers on Facebook—is reflect and amplify many Tunisians’ disenchantment with the country’s political leaders. Precisely because his political project builds on this loss of hope, an accounting of Tunisia’s democratic experiment can help provide a point of departure for any future efforts by veteran and new leaders to revive and rebuild a pluralist democracy. Such a review can also suggest lessons for the West’s many governmental and nongovernmental democracy assistance organizations, some of which have been important, if junior, partners in what now seems like a dream deferred.

Power Sharing as a Temporary Cease-Fire

When Tunisia’s leaders created a constitution in 2014 and then held elections for the presidency and parliament, many Tunisians breathed a sigh of relief. But the power sharing experiment that emerged in the ensuing years did not secure a deeper commitment to a common vision of democracy. Instead, it constituted a temporary cease-fire between rival elites who could not agree on essential issues such as the boundaries between state and mosque, or the role of the state and private sector in an ailing economy.

The power sharing experiment that emerged in the ensuing years did not secure a deeper commitment to a common vision of democracy.

Despite their downsides, these kinds of power sharing agreements are not unusual in new democracies. Indeed, they are often a necessary first step in a longer process that begins with securing a minimal consensus on the rules of the game. This is the easy part. The challenge Tunisia’s leaders faced was to move from a consensus that required the agreement of all the key factions to a democracy in which elections would create a government that spoke for a reasonably coherent parliamentary majority and an opposition that would hold up a mirror to a government as it waited to contest a later election. But this shift never happened. Instead, the parliament provided the umbrella for a perpetual cease-fire between endlessly bickering rivals.

Institutionalizing a Brittle Consensus

While feuding elites drove these dynamics, the very institutions that they forged to channel their disputes ended up amplifying their conflicts. Few of these leaders seemed aware of this paradox or, at least, worried about its implications. The same was true for the western and regional governments that nudged Tunisia’s leaders to “cooperate,” as well as the legions of foreign advisors who came to Tunis to help rival leaders reach some kind of agreement. Getting to some kind of political deal was, in fact, a real accomplishment. Thus, all the players focused on their very real and immediate successes while ignoring some of the downsides.

Take, for example, Tunisia’s much-praised 2013–14 “National Dialogue.” Never in the history of any Arab state had political leaders negotiated the rules of the game for a transition to a genuinely democratic political order. But from the outset, the “Quartet” of four Tunisian NGOS that led the dialogue—especially the Tunisian General Labor Union, or UGTT—believed that one of its key purposes was to level a political field that it feared was tilted toward the Islamist-oriented Ennahda Party. Indeed, the UGTT was always ready to call for a national strike if Ennahda did not compromise. This kind of opportunistic logic is typical in many negotiated transitions. But in Tunisia it was not only all-pervasive; it was buried in an avalanche of celebration, best symbolized by the dialogue’s convenors being awarded the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize. That the dialogue itself had in some ways sustained rather than mitigated elite conflicts is not a message that many of Tunisia’s western supporters—especially those in the NGO world—wanted to hear.

The 2014 Constitution and the new electoral law were both designed to reduce each group’s fears that rivals would use elections and the parliament to impose their own policies.

Similarly, the 2014 Constitution and the new electoral law that leaders adopted at the time were both designed to reduce each group’s fears that rivals would use elections and the parliament to impose policies anathema to their basic interests. To mitigate such worries, the constitution gave ample power to the parliament, but still ensured a strong executive, which most secular-oriented forces sought in order to limit the power of Islamist groups. This system of what the French call “cohabitation” was really a system of “non-habitation,” one that ultimately relied on the personal authority of the president to arbitrate conflicts, thus injecting a major element of unpredictability and potential arbitrariness into the entire political system.

As for the electoral law, it was the product of hours of bargaining conducted with input from western experts. While some Ennahda leaders initially pushed for a first-past-the-post system that might have given them a majority, secular groups insisted on a type of proportional representation that would produce electoral pluralities, and in this way limit Ennahda’s parliamentary seats. Seeking to reassure its rivals, Ennahda accepted the proposed system, thus opening the door to a parliament that could not reach majority decisions on many crucial issues. Although the make-up of the 2019 Parliament was different from its predecessor, it was equally fragmented in ways that only recapitulated the assembly’s previous immobilism.

Civil society organizations, meanwhile, tended to recapitulate rather than transcend many of the divisions that marked the wider political and social arena. If competition over western funding— which was inevitable—sometimes exacerbated these identity dynamics, US democracy assistance analysts and organizations often displayed, at least publicly, a seemingly inexhaustible enthusiasm for NGO leaders, the majority of whom were secular and had lived or been educated, at least for a time, in western Europe or the United States.

Family, Personal, and Identity Squabbles

These and other institutional arrangements provided a powerful incentive for leaders to avoid rocking a power sharing boat whose passengers included leftists, ultranationalists, liberals, and Islamists of different stripes. The challenge facing all these leaders was to maintain their credibility with their own parties’ faithful while also remaining loyal to the ship of state. Managing this familiar dilemma was a full-time job, one that proved especially difficult in a context of intense elite divisions that were as much, if not more, about family and personal squabbles as they were about ideology or Islamist-secular disputes.

During the first couple of years of Tunisia’s new democracy these squabbles seemed manageable. Reports from Washington think tanks and democracy assistance organizations were mostly positive, or at least hopeful, underscoring a sense that Tunisia’s young democracy was experiencing natural growth pains. But by 2018, political infighting had intensified, thereby threatening to destabilize the already tenuous 2016 power sharing arrangement—known as the Carthage Agreement—between then President Beji Caid Essebsi’s Nidaa Tounes Party and Rachid Ghannouchi’s Ennahda Party.

These dynamics were only partly a consequence of long-standing disputes regarding the relationship between mosque and state. Indeed, the core problem was that rival elites in Nidaa Tounes used Islamist-secular conflicts to undermine their foes, thus further polarizing the political system. This toxic dynamic had already taken its toll two years earlier, when President Essebsi tried to groom his son, Hafedh Caid Essebsi, to assume leadership of the party. This effort not only sparked resistance at the upper echelons of the party, it also damaged Essebsi’s reputation as a leader who was above the political fray. That the very president who had been seen by many as a symbol of national unity was fostering a kind of secular sectarianism telegraphed for all to see that the highest position in the land was now just another weapon of political warfare. Moreover, with the balance of power now disrupted, internal power struggles in other parties intensified, as rivals debated how to best respond to Nidaa Tounes’s escalating conflicts and looming implosion.

In Ennahda, these debates pivoted around the fundamental question of the role of religion in the party’s political activities. During its October 2016 party congress, new rules were adopted that precluded MPs from holding leadership positions in religious organizations, and in other civil society organizations as well. This decision underscored the desire of some party leaders, including Rachid Ghannouchi, to signal that Ennahda was not pursuing an Islamist agenda. Essebsi reciprocated by giving the keynote address at the party’s congress, during which he praised Ennahda. But as challenges to Essebsi and his son escalated, the president retaliated by accusing his rivals of working with Ennahda to undermine him. He then declared the end of power sharing, a clear bid to isolate his enemies in Nidaa Tounes.

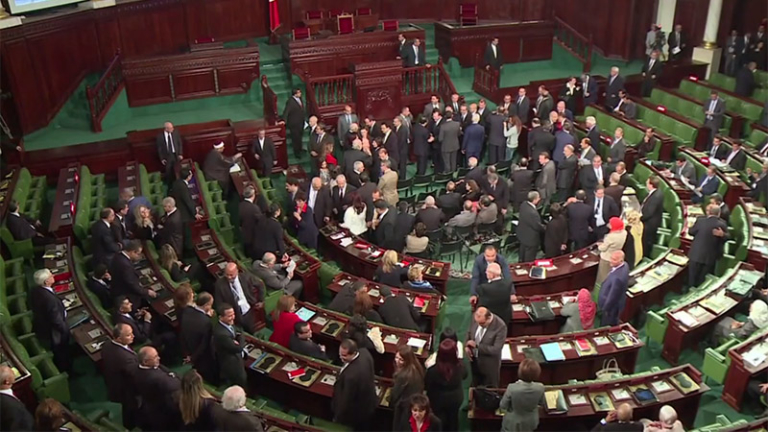

A Paralyzed Parliament Becomes a National Embarrassment

With his partnership with Essebsi in tatters, Ghannouchi faced increasing criticism from rivals in Ennahda, who accused him of making concessions to Essebsi for which he got nothing in return. Seeking to outflank his critics, Ghannouchi declared that he would run in the October 2019 parliamentary elections. Ghannouchi not only won, he was then elected speaker of parliament. His sudden rise to a leadership position sparked intense criticism in his party and some 100 resignations, not to mention intensified conflict in parliament, as his anti-Islamist rivals mobilized. In the ensuing year and a half, Tunisians were treated to televised images of MPs quarreling and even coming to blows.

Ghannouchi did not help matters when he met with Erdoğan in January 2020.

Ghannouchi did not help matters when in January 2020 he met with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Istanbul. The trip provoked stern criticism from President Kais Saied and outrage from many secular-oriented MPs who despised Erdoğan and his Islamist Justice and Development Party. Seeking to exploit Ghannouchi’s troubles, Abir Moussi, the leader of the Free Destourian Party, unsuccessfully pushed to impeach the speaker. When Ghannouchi then banned private security guards from entering the assembly, Moussi—who had previously claimed that she and her allies were facing physical threats from Islamist leaders—pulled a publicity stunt by taking her seat in parliament wearing a motorcycle crash helmet and a bulletproof vest. If the bizarre image of Moussi clad in a shiny white robocop outfit was meant to discredit Ghannouchi, her grandstanding only reinforced the view of many Tunisians that the national assembly was a national embarrassment. Underscoring the parliament’s decreasing legitimacy, only 41 percent of registered voters went to the polls in 2019, compared to 68 percent in 2014.

That Moussi’s theatrics unfolded at the same time that then Prime Minister Hichem Michichi announced that Tunisia would seek a $4 billion IMF loan was telling. One of the consequences of parliament’s incessant infighting was the inability of each and every successive government to secure majority support for any economic reform plan. As a result, government deficit spending skyrocketed while economic corruption proliferated.

The parliament’s paralysis stymied vital legislation on other key issues, such as appointing a Constitutional Court. As set out in the 2014 Constitution, once constituted, the court would have the right to judicial review. But precisely because the court would have wielded this power, MPs opposed the nominations of their rivals, thus repeatedly delaying the creation of the court. By the time some MPs realized the high price that they were paying for their incessant infighting, it was too late. Fearing that the court would be used against him, Saied vetoed a proposed law that would have streamlined the appointment procedures for the court.

All of this maneuvering unfolded against the backdrop of the stark failure of the public health authorities to address the escalating COVID-19 health crisis. Seeking to highlight the weakness of state institutions, days before his July 25 power grab, Saied announced that the military would dispense COVID vaccines. This clever move played into a widely shared view that the military was the only effective national institution. Thus, with very little public outcry Saied deployed soldiers to prevent MPs from entering the parliament, and then turned to the military courts to prosecute several of his critics. However illegal, unconstitutional, and morally repugnant these moves were, he advanced his autocratic project by exploiting mass disappointment with political leaders, whose petty battles appeared far removed from the daily struggles of many Tunisians.

The Limits and Paradoxes of Western Democratic Assistance

In January 2021, the International Republican Institute issued a report titled, “Tunisia Needs a Constitutional Court as Soon as Possible.” No one would contest this point, even if it came late in the day. But the more fundamental need is to question what US officials, policy experts, and democracy assistance activists could have actually done to break through the imbroglio of elite infighting that prevented the creation of the court. The answer is: probably very little. Underscoring this reality, when western experts advocated a reform of the electoral law that might have produced a legislative majority, they got few takers. Since each party feared that its rivals would benefit from such a change, in the run-up to the 2019 election there was no effort to reform the election law.

If fostering reforms in the political arena has proven tricky, finding allies to push for reforms in the security sector has proven even harder. This author, for example, flew to Tunis many times to facilitate projects designed to secure such allies. Tunisian colleagues were cordial, but despite millions of dollars being spent by European and US organizations, these and other efforts collided with deeply entrenched institutions and practices. Facing such realities, US officials and democracy assistance activists have chosen to work with those leaders who they presume have real power and resources. As in Iraq and Sudan, the power sharing deals that the US has promoted—and sometimes celebrated—ended up prolonging rather than overcoming conflicts. The United States has yet to figure out how to avoid this outcome by helping rivals to move beyond the limits of a fragile consensus that has undermined the legitimacy of the very elites it has backed.

This does not mean that the US should retreat from supporting democracy and human rights in the Middle East. But it needs to pursue this endeavor with both eyes open, rather than downplaying signs of trouble. At the same time, it must think carefully about how to protect its partnerships with colleagues on the ground. Dramatic steps, such as petitions calling for the sanctioning of a president or ministers, may feel and sound righteous. But they could also make life worse for democracy activists seeking to survive another day. The challenge is thus to grapple with this dark moment so that the quest for democracy can be renewed in the not-too-distant future.

The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

Fetured image credit: Présidence Tunisie