Since October 2016, the Iraqi government, supported by the US military, has waged one of its most difficult battles to regain the important city of Mosul. The previous government of former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki had opted to leave the city without a fight three years ago, when Maliki ordered three Iraqi army and security divisions to withdraw, leaving their brand new heavy armaments to the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). This was a questionable decision for which neither Maliki nor any of his commanders were held responsible or accountable. It is still not clear if there will be an open and public investigation. What is known is that 35 high-level political and military leaders, including Maliki, have not paid for the dismal Mosul failure of 2014. Indeed, nine of those have already fled the country and rumors abound about a cover-up.

The Mosul Decision

After three years, the Haider al-Abadi government decided to proceed with plans to regain the largest Sunni Arab city in Iraq, and its second largest city overall. The United States extended both technology and advice to the Iraqi military and security forces along with the needed air cover and support, without which the aim of regaining the city would have been very difficult.

The complications that previously faced the operation to regain Mosul continue to impact the military and humanitarian situations. The role of the Shiite militia, the People’s Mobilization Forces (PMF), is still perceived with apprehension by the Sunni population of Mosul and the surrounding tribes. Simply, they are not welcomed in the region because of the history of persecution, killing, and suppression of the local Sunni population of Diyala, Tikrit, Ramadi, Jurf Al-Sakhar, Fallujah, Baiji, and others. People from these areas have complained about a strategy the Shiite forces have pursued before and are afraid that they will repeat: to stay behind until ISIS resistance ceases and then to sneak behind the security forces to start their aims of destroying the infrastructure, persecuting the population, looting, and preventing the local population from returning.

The complications that previously faced the operation to regain Mosul continue to impact the military and humanitarian situations. The role of the Shiite militia, the People’s Mobilization Forces (PMF), is still perceived with apprehension by the Sunni population of Mosul and the surrounding tribes. Simply, they are not welcomed in the region because of the history of persecution, killing, and suppression of the local Sunni population of Diyala, Tikrit, Ramadi, Jurf Al-Sakhar, Fallujah, Baiji, and others. People from these areas have complained about a strategy the Shiite forces have pursued before and are afraid that they will repeat: to stay behind until ISIS resistance ceases and then to sneak behind the security forces to start their aims of destroying the infrastructure, persecuting the population, looting, and preventing the local population from returning.

After much regional and international—including American—pressure on Haider al-Abadi, the government decided not to give the PMF a role in regaining Mosul as before. Instead, they were entrusted with the role of regaining Tal Afar, a mostly Turkmen city to the west of Mosul with a mix of a Sunni majority and Shiite minority. The PMF militia members have vowed revenge against what they call ISIS; but to the Sunnis that means they themselves are the targets. Turkey has intervened and expressed its opposition to any role for the Shiite militia, vowing to prevent a “massacre” planned by the PMF in the city against the Sunni Turkmen and Sunni Arabs.1 The Turkish factor should be taken into consideration whenever the Mosul question is raised because Turkey has made it clear that any targeting of Sunni Turkmen in the city will face a drastic reaction on the part of Turkey.2

In fact, Mosul as well as the Sunni Arab population of Iraq have been victimized both by ISIS, which calls them apostates, and the Shiite sectarian politicians, who hold them responsible for the martyrdom of Imam Hussein 1,350 years ago. The failure of the Iraqi government to part with these illogical claims and slogans makes its mission in Mosul complicated and difficult. In fact, the people of eastern Mosul welcomed the security forces until it became clear that the PMF were going to be involved, so they rejected their participation. The same is to be expected on the western side of the city.

Facts on the Ground

The following are important considerations in the Mosul operations:

- The American presence on the ground now encompasses not only a role of advice and consultation but as fighting forces on the battlefield. This increase in American involvement has direct impact on the rules of engagement. A series of tactical directives were issued to meet these developments. More advisors were embedded with the Iraqi forces to guide Iraqi tactical commanders, which resulted in closer coordination, more flexibility, and less bureaucracy.

- The Iraqi air force has started to take a more active role in targeting ISIS in western Mosul.

- There are one million inhabitants on the western side of Mosul who will undoubtedly suffer casualties from ongoing operations.

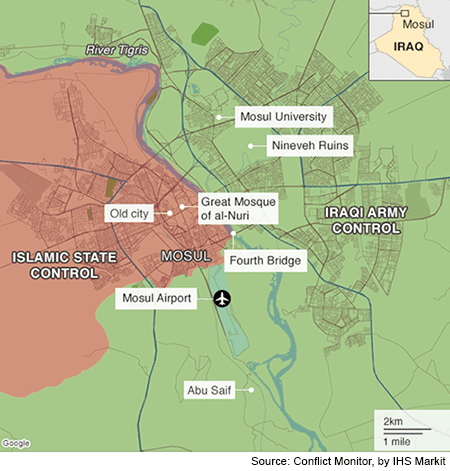

- City streets in the western side are narrower and may not facilitate the movement of armored vehicles, which may limit the tactical edge of the armed and security forces.

- The western side of Mosul is a strategic communication center which opens the field westward toward Raqqa, ISIS’s stronghold in Syria, the Kurdish-held part of northeastern Syria, and Mount Sinjar with its Yazidi population. The Baghdad highway begins in the western side.

- The main airbase at Qayyara in northern Iraq is only 30 miles or so south of Mosul, while the civilian airport and the old Mosul air base are located on the southern reaches of the city.

- The Iraqi ninth division, which was tasked with leading the advance and storming Mosul from the south, succeeded in regaining a couple of villages and the airport area on the southern fringes of the ISIS-occupied city. The division succeeded in occupying the airport and the Ghuzlani military cantonment. The division is expected to face more resistance from ISIS until the organization decides to disengage, by which time the battle for Mosul would end.

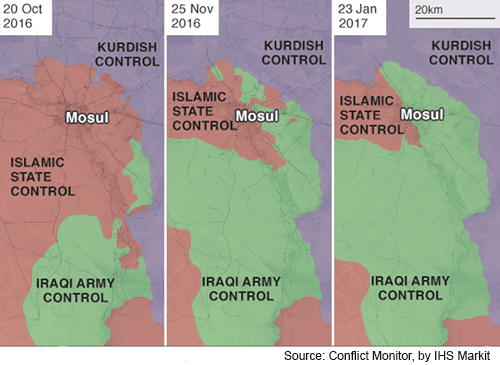

- One scenario is that ISIS chooses to disengage from Mosul and continue to fight in and around Tal Afar up to the Syrian border after it secures a corridor for its retreat. The alternative is to continue fighting to the last soldier. The maps herein show how the Iraqi forces expanded their area of control over Mosul on the eastern and western sides of the Tigris. It is thus important to maintain the thrust and concentration of power over the weak areas; this may give Iraqi security forces an edge over ISIS which, after all, may decide to disengage if an escape route were to open.

- In this case Tal Afar and its surroundings will witness the final battles on Iraqi soil against ISIS. This battle will most likely be a direct dogfight between ISIS on the one hand and the Shiite militia and their Iranian mentors on the other.

- Iran’s direct involvement in the battle for Mosul through the PMF will serve its double aims of 1) gaining a foothold in Tal Afar, where the Shiite minority may be given assistance to dominate the city, and 2) securing a strategic axis that links it to the eastern Mediterranean through Iraq. This latter goal has added one more factor to the accumulated Turkish-Iranian differences over Iraq and the strategic role of both countries in the Middle East.

The battle for Mosul and its consequences will not end the violence nor the differences over the future of Iraq as a state, the relationship between the Sunni population of Iraq and the central government, the issue of disputed territories between the central government and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), and the future of Islamic fundamentalist movements and militias, both Sunni and Shiite, which would like to decide the future of the country.

The Humanitarian Factor

The Iraqi people are victimized by the prevailing powers no matter what their affiliation, but the fact that a real war is underway in the Iraqi Sunni areas since the invasion of 2003 and occupation of the country made these the most affected parts from a humanitarian point of view. At least 11 million people, mostly Sunni Arabs, live in these areas and all were severely victimized by the occupation powers, the insurgency, Al-Qaeda in Iraq, the Iraqi government’s security forces, the Peshmerga, the Shiite militias including the PMF, and ISIS, which treated them as apostates to persecute and kill.

As for the present ongoing battle for Mosul, which is populated by more than two million people, suffering is prevalent. The United Nations estimates that no less than 175,000 people fled their homes since October, when the battle to regain the eastern side of the city was raging. Until now no more than 30,000 have managed to return and it is unknown what the destiny of the rest will be like considering fears from the PMF. On the western side of the city, where 800,000 live, the picture is grimmer. The population is the most victimized in this massacre that spared no homes, no bridges, no universities and educational establishments, and no infrastructure. It is indeed feared that a predesigned plan is afoot to render all the cities of the Arab Sunni areas uninhabitable.

1 There were many statements and counter statements about the role of the PMF in Tal Afar among Turkish officials. It is important to note that the commander of the PMF, Hady Al-Amiri, and his deputy, Jamal Al-Wakeel (known as Abu Mahdi Al-Mohandas), both have Iranian citizenship and are members of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC).

2 Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Prime Minister Binali Yildirim, and Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs Mevlut Cavusoglu expressed Turkish sensitivity regarding Mosul, Tal Afar, and Sinjar.