While a positive development, the recent defeat of the so-called Islamic State (IS) in Raqqa, Syria, has added unforeseen complications to the Syrian crisis. The fact that Raqqa’s liberation took place mostly at the hands of Kurdish troops belonging to the US-supported Syrian Democratic Forces has thrust the prospect of ethnic conflict forward, since the Raqqa Governorate contains only a small Kurdish presence and is mainly Arab. Kurdish control also irks Turkey, which has cautioned the United States against supporting the People’s Protection Units; Ankara credibly fears that they have ambitions to form a Kurdish enclave on Turkey’s southern border. Russia does not seem too worried about these developments, and the United States is apparently unable to influence events related to the future of the Syrian regime; such a scenario ensures that confusion and instability in the region will continue for a considerable period of time.

While previously neglected by the Syrian government and media, Raqqa achieved notoriety after IS occupied and declared the city its capital in January 2014. The organization went on a killing spree of journalists, emergency management personnel, and local and foreign civilians, in the process awakening western public opinion and official interest. But the decisive factor was IS’s attacks in western cities like Paris and Brussels, which prompted a radical change in American policy toward Syria and a shift away from concentrating on the Assad regime and its crimes against Syrian civilians. Dealing with the Islamic State became the object of American political and military efforts aimed at eradicating the organization, with scant reference to the Syrian regime or to how to resolve the Syrian civil war.

Anti-Islamic State US Allies

The Obama Administration’s decision to forsake dealing with the political transition process in Syria and concentrate solely on destroying IS in Raqqa and elsewhere prompted heated debate in government circles about the type and identity of potential “allies” in the anti-IS struggle. This search had to be conducted without consideration of the opinion of the Assad regime; and that is in contrast to the case of Iraq, whose central government cooperated with the United States in its efforts to defeat IS in Iraq’s west and northwest. In the beginning, the United States tried to recruit and arm units of deserters from the Syrian army, but the idea failed when they refused to coalesce on defeating IS instead of the regime that was responsible for repression and the war in the first place.

The battle against IS began in 2014 when the organization attacked the border city of Ain al-Arab (the Kurds refer to it as Kobane) and tried to overtake it. The city had been under the control of the People’s Protection Units (YPG), long seen as the Syrian affiliates of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) since July 2012. The YPG defended the city with help from the American-led international coalition and succeeded in breaking the IS siege on it. But although it was a military victory, Kobane emerged as the cause for a breach of confidence between the United States, which aided the Kurds, and Turkey, which had great hesitation about supporting Kurdish military units aiming to establish their own canton on the Syrian-Turkish border. From its side, the YPG was a useful ally to the United States. On the one hand, its fighters were good and reliable, having received training and experience from their close association with the PKK. On the other hand, they were uninvolved in the fight against the Assad regime and thus could be used solely for fighting the Islamic State.

But this association was fraught from the beginning. Exploiting the situation on the ground and the Syrian regime’s neglect of its objectives, the YPG saw a strategic opportunity to expand the areas of Kurdish control in northern Syria beyond the three cantons—Hasaka, Afrin, and Kobane—over which they had gained control with the help of none other than the Syrian regime itself. By that time, the United States had prevailed upon the YPG to become part of what later became known as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which also included small contingents of Arab tribal fighters. This gave the impression that the Kurds were not the only friends of the United States in Syria.

US support for the YPG increased with Donald Trump’s election as president. Eschewing direct involvement in military operations, Trump gave American generals the authority to decide what is best on the battlefield in northern Syria. At the same time, they were to increase the number of aerial bombing runs against IS in Raqqa, and this led to a large increase in civilian deaths. What was important for the Trump Administration was a quick military victory over IS in both Syria and Iraq. Simultaneously, this led to an open dispute with Turkey, which had declared YPG a terrorist organization and tried to convince the United States to rely more heavily on Syrian opposition forces in liberating Raqqa.

Nonetheless, Washington insisted on its policy of arming and supporting the SDF which, after a five-month campaign, succeeded in liberating the city after occupying Tabqa and other towns surrounding Raqqa. The White House took credit for the victory, with President Trump announcing in a statement released by the White House, “The defeat of ISIS in Raqqah represents a critical breakthrough in our worldwide campaign to defeat ISIS and its wicked ideology. With the liberation of ISIS’s capital and the vast majority of its territory, the end of the ISIS caliphate is in sight.”

The American-Russian Dynamic

American efforts over the last few months to negotiate with Russia about Syria may have failed because of Russia’s insistence on the security and military aspects of the Syrian conflict instead of focusing on the process of political transition and Assad’s future. In fact, Russia has protected Assad over the years; the last such effort, the ninth of its kind, was when it vetoed an American proposal to renew the United Nations Security Council investigative commission charged with looking into responsibility for the use of chemical weapons, itself established according to an American-Russian agreement. Preliminary investigation by the commission found that the Assad regime was responsible for using these weapons in Khan Sheikhoun in the Idlib Governorate in April 2017. At any rate, it appears that the Trump Administration may have arrived at the conclusion that cooperating with Russia in Syria will not produce the necessary results—thus the seeming US abandonment of efforts to effect any change in developments there.

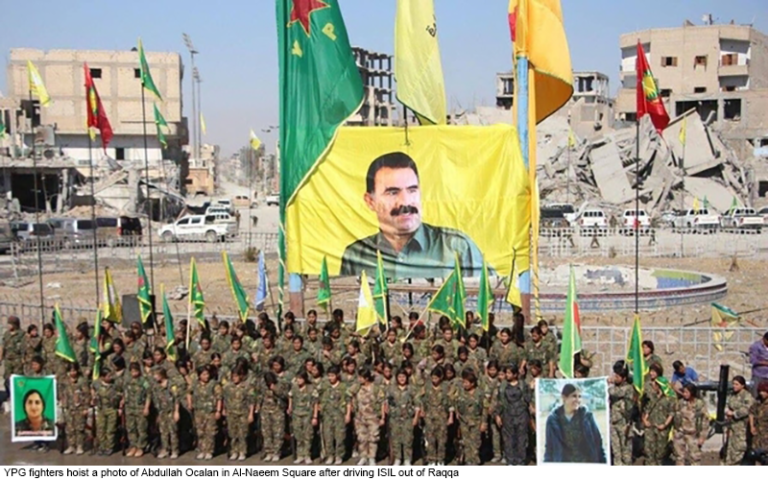

This American disengagement and dependence on the Kurdish YPG prompted Turkey––long a US NATO partner––to coordinate more closely with Russia, specifically at the Astana negotiations, whose seventh round will be held this week. As before, this round will concentrate on guaranteeing the establishment and protection of de-escalation zones in Idlib and on reaching agreement about procedures for exchanging information and releasing political prisoners. It further seems that Turkey is preparing to face the steps the YPG might take after controlling Raqqa and hoisting pictures of PKK imprisoned leader Abdullah Ocalan in the city’s main square. This last gesture riled Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his government but elicited a less persuasive response from the US Departments of State and Defense. Ankara is now waiting to see whether Washington will recall the weapons it previously gave the YPG to fight IS and what policies the YPG will pursue in administering—and perhaps trying to expand—the liberated areas.

At any rate, Erdoğan has asserted that the Turkish military will likely direct its attention to Afrin, which is controlled by the YPG—a potentially violent battle that would test the mettle of his forces. Simultaneously, because of Turkey’s doubts about American objectives in Syria, it is likely that Ankara will concentrate for at least the time being on strengthening its relations with Moscow, something that is clear from the current military discussion at Astana. The fall of Raqqa will most certainly deepen this cooperation at the expense of the United States and this, in turn, will expand into coordination for the future battle of Deir Ezzor to liberate it from IS. At present, there does not appear to be any Russian-American coordination for that battle, which means that northern Syria may see a division on the ground between an American-influenced zone around Raqqa (because of the YPG’s role) and a Russian-Turkish zone around Deir Ezzor, al-Mayadeen, and other areas in the oil-rich governorate. Indeed, this is a reminder of the “useful Syria” mantra voiced by Assad a few years ago.

The Post-Raqqa Period

The Raqqa battle was not as difficult as the one earlier in the year for control of Mosul. The United States increased its air operations in an unprecedented fashion, which resulted in the death of hundreds of civilians. Still, the civilian death toll received scant attention from observers and the media in the United States. Russia was quick to use the death tolls to disparage the American effort to liberate the city and to criticize the US-led coalition for bombing the Syrian city of Raqqa “off the face of the Earth.” Attention now centers on the post-Raqqa period since Syria’s map has become much more complicated and in need of an international political, diplomatic, and perhaps military involvement in the Syria crisis.

President Trump spoke of a new period during which the United States “will soon transition into a new phase in which we will support local security forces, de-escalate violence across Syria, and advance the conditions for lasting peace, so that the terrorists cannot return to threaten our collective security again. Together, with our allies and partners, we will support diplomatic negotiations that end the violence, allow refugees to return safely home, and yield a political transition that honors the will of the Syrian people.”

The US president thus knows that there is an urgent need for an American strategy in Syria after Raqqa, one that takes into account the security, military, and political aspects of the conflict instead of concentrating only on single pinprick operations like the raid on the Shayrat air base following the Khan Sheikhoun chemical weapons attack. Unfortunately, however, the administration does not seem to understand the negative repercussions from the absence of a comprehensive strategy—in the past and present. Instead, the United States has focused its efforts on defeating IS and neglected the Syrian opposition’s and Turkey’s calls for reliance on the Free Syria Army to achieve that goal. After the fall of Raqqa, the US approach of arming and supporting the YPG may allow the Kurds to try to secede, which, in turn, would lead to the dismemberment of the country. This contradicts the administration’s stated goal of preserving Syria’s unity and territorial integrity.

These developments have increased doubts among Turks and the Syrian opposition about US credibility and believability when it says that it will have a comprehensive strategy to deal with Syria. An important pillar of such a strategy is achieving a political transition that assures Bashar al-Assad’s departure. After all, this was Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s announcement, that “the reign of the Assad family is coming to an end.”

As things stand today, US support for the YPG has allowed the militia not only to occupy Raqqa but to announce its intention to add the city to what it calls the administrative districts it already controls, according to its unilaterally declared federal system. The federalism that the YPG’s political arm, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), declared is not suitable for Syria and will only lead to continued civil strife after the end of the battle against the Islamic State. It will also lead to disputes and probably open warfare between the Kurds and Syrian Arab tribes in Raqqa, where the Kurds constitute a very tiny minority.

The chiefs of the Arab tribes and clans issued a series of declarations complaining about the role played by the YPG in liberating Raqqa and criticizing the American reliance on them to the exclusion of others. Ignoring these calls will only complicate the peace process in the transitional period in Syria. The United States must participate in this process by pushing for a transition; it must also exploit its resources and diplomatic and political clout to assure battlefield successes, paving the way for a future Syria.

While news of the liberation of Raqqa from IS met with widespread approval among all Syrians, the Kurds’ control of the liberated city and its surroundings prompts serious questions about the future. Syria awaits an end to the war that has destroyed its cities and rendered millions of its people homeless, internally displaced, and refugees. The United States has the moral and political responsibility to ameliorate hardships and provide for an equitable and sustainable solution for the war in Syria.