The world today is facing an unprecedented crisis of human displacement. About one of every 95 persons is displaced from his or her home due to persecution, war, and climate degradation. According to the United Nations, 5.2 million Ukrainians have been made refugees in neighboring countries, of a total of some 11 million who have fled their homes since the beginning of the Russian invasion on February 24. The human toll will extend far beyond the immediate violence of the Russian invasion because those who suffer persecution and war are often condemned to endless diaspora where traumas are carried, deaths are mourned, and destroyed places are dearly missed.

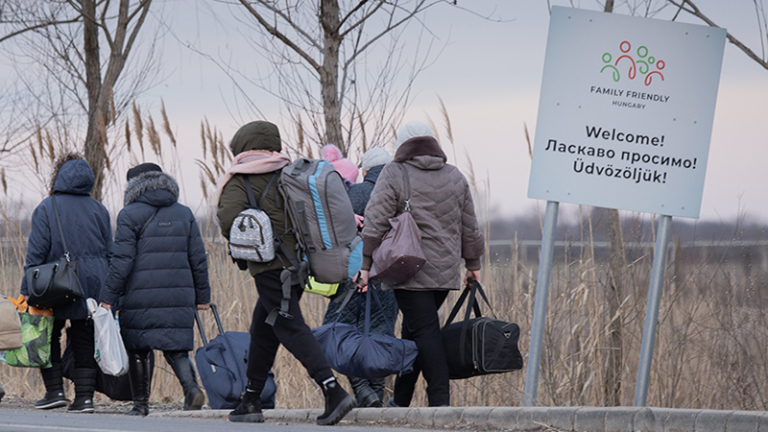

While all displaced people suffer these high costs of war, not all are offered the same respite. The Ukrainian displacement crisis has captured global attention, but it has also exposed the double standard in the treatment of those seeking refuge. Ukrainians are rightfully being welcomed, but their welcome is taking place across the very same borders where others—from Syria, Afghanistan, Eritrea, and Haiti, to name a few—have systematically been denied entry.

For the majority of the world’s displaced, to be forced to leave home is to contend with a global patchwork of unequal borders designed to exclude those who need resources and stability from countries that have it.

However, focusing only on this blatant racism misses the status-quo of exclusion that predates Ukrainian displacement. For the majority of the world’s displaced, to be forced to leave home is to contend with a global patchwork of unequal borders designed to exclude those who need resources and stability from countries that have it. To understand the global displacement crisis, and why countries in the South-West Asia and North Africa (SWANA) region are the epicenter of it, is to comprehend how histories of colonialism and presents of racism conspire to shape the permeability of borders.

Race, Colonialism, and Borders

Racism shapes possibilities for refuge. Media commentary on Ukrainian displacement made this mechanism clear. A Ukrainian politician, for instance, said the war was emotional because it involves “European people with blonde hair and blue eyes being killed.” An Al Jazeera journalist said those fleeing are “prosperous, middle class people” and “are not obviously refugees trying to get away from areas in the Middle East that are still in a big state of war…they look like any European family that you would live next door to.” A CBS News senior correspondent added “This isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan that has seen conflict raging for decades. This is a relatively civilised [sic], relatively European—I have to choose those words carefully, too—city where you wouldn’t expect that, or hope that it’s going to happen.”

These statements evoke the work of Palestinian scholar Edward Said who, more than forty years ago, wrote that in a postcolonial era, the West continues to portray itself as “civilized” against the uncivilized, primitive, brutal “Orient.” This portrayal, upheld in artwork, entertainment, and media coverage, serves to dehumanize, to make the lives of people in the “East” or “South” less meaningful, and their deaths less worthy of an emotional response. Before Ukraine, more than 80 million Black and brown displaced persons did not seem to warrant such a response, indicating that race determines whose lives are valued, and who is cast aside as a “refugee crisis,” a “scourge,” or a mass of “illegals.”

This devaluation of human life shapes the permeability of borders. Countries in Europe, as well as the United States, are complicit in the colonial legacies, foreign military interventions, and environmental degradations that refugees are fleeing. Yet, people show up at their borders to attempt to access the safety, economic resources, and possibilities that these countries have, but they are repelled—with walls, digital technologies, and police brutality.

Countries in Europe, as well as the United States, are complicit in the colonial legacies, foreign military interventions, and environmental degradations that refugees are fleeing.

They are also repelled with laws. At the United States southern border, Title 42, a public health doctrine, initially evoked by the Trump Administration and is kept up by Biden’s, was used to keep out hundreds of thousands of asylum-seekers. It was applied to Ukrainians too, until Customs and Border Patrol were told to use their discretion when it came to them. The European Union is building prison-like “Closed Controlled Access Camps” on the Greek Aegean islands to limit the mobility of asylum-seekers. While European countries argued that they could not handle the influx of refugees, they now offered blanket three-year residencies through the Temporary Protection Directive (TPD) to all displaced Ukrainians. This indicates that the issue with inclusion was never one of capacity, but of political will.

The Middle East as an Epicenter of Displacement

It is partly because of colonial history that countries in SWANA have become an epicenter of the global displacement crisis. The boundaries around states in this region were drawn by colonial hands. Palestinian displacement cannot be understood without looking at the British mandate. The Syrian civil war is a product of authoritarian repression originating in the French colonialists’ divide-and-rule strategy. Displacement is also fueled, along with violence in Iraq, by American imperialism—the so-called Islamic State, a key actor in these conflicts, was born in Camp Bucca, a US-run prison. Even the term “Middle East” has come under criticism for its colonial roots, with some activists and scholars preferring to use the decolonized SWANA instead.

The lack of resources available to displaced people from the region, and the impermeability of borders around it have resulted in a situation where the majority of people who are displaced never leave their country of origin. There are an estimated four million Yemenis, six million Syrians, and one million Iraqis who are displaced within their own country. The majority of those who do leave (nine in ten) are likely to remain in countries that are immediately proximate to their own—meaning that they also never leave the region. Turkey, Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon, countries that face their own infrastructural challenges, are tasked with facing the humanitarian crisis of displacement. Lebanon, for instance, a country with a population of 6 million, is embroiled in its own devastating financial crisis but continues to host approximately one million Syrian refugees.

Turkey, Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon, countries that face their own infrastructural challenges, are tasked with facing the humanitarian crisis of displacement.

Within these countries, refugees have become politicized and marginalized. In Turkey, the mood toward Syrian refugees has reportedly shifted over the last eleven years of the war, with many voters wanting them repatriated. Syrians in Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon, are often unable to obtain work permits, are subjected to hate crimes, and have limited access to health care. Education is a huge concern for refugees: in Jordan, for instance, a recent report showed that rates of enrollment in secondary school for Syrian students hover between 25 and 30 percent. This means that a whole generation of Syrian children are being denied a basic human right, and a crucial tool for building prosperous, dignified futures.

International Non-Governmental Organizations in the region have long asked wealthier countries to contribute to alleviate this humanitarian crisis. And while there have been contributions, they fall drastically short of the need, particularly for long term educational and health care programming. Given that most displaced people will remain in countries of immediate refuge indefinitely, there’s a real need to support the countries receiving them. But as conflicts rage on, more should be done to provide safe channels for people to move to countries where their legal status is secure and basic needs are fulfilled. Globally, however, these channels are increasingly narrowing and closing, turning the legally sanctioned pursuit of refuge into a hostile, and sometimes deadly, maze.

Refuge Denied

For those who want to secure new beginnings and dignified lives—where they can have legal status, work jobs that offer economic returns, access health care, and procure an education for their children—the solution is often to continue traveling in pursuit of refuge. In doing so, they find themselves knocking on the doors of the very same countries whose foreign policies have subjugated either them or people like them, and whose domestic policies are patterned by the same racism that facilitated those foreign policies. These journeys are marked by the brutality of border denials, but also by racism in the domestic sphere for those who do get in.

Specifically, there are two legal avenues for permanent solutions to displacement. One is resettlement, where countries, after a process of vetting, offer displaced people legal status and admit them. Another is asylum, where after what is often a very dangerous journey over land and sea, a refugee shows up in a new country and applies for legal status. For the vast majority of the world’s refugees, both avenues have been virtually shuttered in recent years.

Resettlement is a rare solution, offered by less than thirty countries and available to less than one percent of displaced people each year.

Resettlement is a rare solution, offered by less than thirty countries and available to less than one percent of displaced people each year. The United States led globally on the number of people resettled each year from 1980 until 2017, when the program was dismantled by the Trump Administration that was motivated specifically by anti-Muslim and anti-Syrian sentiment as well as the racist idea that Syrian refugees were trojan horses for terrorism. The program, however, was not reinstated by the Biden Administration. Even while committing to welcoming 100,000 Ukrainians through a mix of humanitarian parole and resettlement, the Biden Administration has only, to date, admitted less than 9,000 people through resettlement despite a commitment to admit 125,000 by the end of this fiscal year (September 30). This leaves millions of people in countries of immediate displacement in the lurch.

The denial of refuge is also true of the European system, which this author has observed last fall as part of research for a new project on borders. In 2015 a million people took boats across the Aegean, and were able to make it into countries in Europe, due to a temporary suspension of the Dublin Regulation (which would have required them to stay at the European periphery). Since then, however, these countries have closed their doors to new arrivals. Today, anyone attempting to journey to Greece, across the Aegean Sea or through the land border at Evros, experiences pushbacks. Greek authorities, with the help of Frontex (European Border and Coast Guard Agency), break migrants’ boat engines and, against international law regulations, pull them back into Turkish waters.

Refugees also live in prison-like conditions when they arrive on Greek shores. They are housed in European Union-funded “Closed Controlled Access Centers,” which are holding camps from which they cannot exit except with a temporary permit. On Sundays, they are disallowed from leaving because Greeks supposedly “deserve a day for themselves.” These camps hold Syrians, Iraqis, Palestinians, Sudanese, Eritreans, and Afghanis who arrived at different times but under similar circumstances of displacement.

When refugees arrive in the United States, Canada, or Germany, they still have to contend with systems that see them as outsiders.

When refugees arrive in the United States, Canada, or Germany, they still have to contend with systems that see them as outsiders. In the United States, Syrians who settled in Connecticut in 2015, were the targets of inflammatory rhetoric and travel bans. In Germany, they were expected to conform to notions of leitkultur, or “leading culture,” one that German Minister Thomas de Maizière defined by not shaking hands across genders and not wearing Burkas —practices that some Muslims observed. In this way, systematically, even when they’re offered legal protection, refugees from the Middle East, and from elsewhere in the world, are not made to feel welcome. Their potential as human beings, their skills and abilities, their hopes and aspirations for themselves and their children often go unheard.

Watching the welcome of Ukrainians at the same borders where others have been denied entry is an invitation to imagine what is possible when refugees fleeing atrocities and wars are seen as human beings. Looking at migrants from a humanitarian perspective and finding the political will to include them as equals will undoubtedly ease the impact of the devastation they experienced. By the same token, host countries gain morally and materially by welcoming refugees as human beings crossing borders and deserving assistance instead of as security risks or burdens on national treasuries.