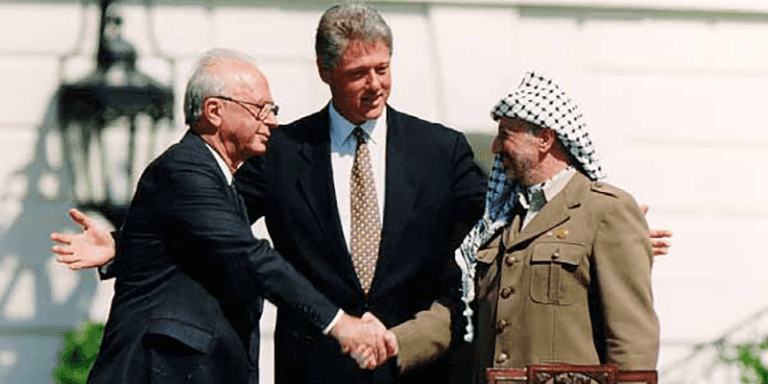

The Oslo peace process was initiated with an iconic handshake in the White House’s Rose Garden 25 years ago. Today, it appears to be dying of neglect and the Trump Administration’s repeated and misguided efforts to dismember it. On September 13, 1993, US President Bill Clinton, Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman Yasser Arafat, and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin gathered in Washington to mark the signing of the Oslo Accords; long before the handshake photo op, however, many political factors and conditions had set the stage.

Genesis of the Oslo Peace Process

The Oslo Accords signified a new dynamic where both the Israelis and Palestinians saw an interest in direct negotiations mediated by Washington. To create that condition, a number of changes took place. First and perhaps most important was the first intifada. The Palestinian uprising against Israel, which began in December 1987 and lasted for several years, featured organized protests and demonstrations as well as limited armed resistance. The military response by the Israelis focused the world’s attention on their repression of a stateless people yearning for rights that had been denied to them for decades.

For the Palestinians, this was a source of leverage. The world was changing, old structures were being dismantled, and the cold war was ending. Israel had a peace deal with Egypt, the Camp David Accords. Israel’s excuses not to make peace with the Palestinians were less compelling, and the uprising crystallized this reality. As South Africa was transitioning from an apartheid state to a democracy, Israel began to perceive sharply what costs international isolation might entail.

Israel’s military response to the first Palestinian Intifada focused the world’s attention on its repression of a stateless people yearning for rights that had been denied to them for decades.

But the intifada was a motivator not only for the Israelis but also for the Palestinian leadership which, prior to the Oslo Accords, was based out of Tunis and operating in exile. Having propelled the Palestinian cause onto the international agenda in the 1960s and 1970s, the PLO was now energized by a younger generation playing this role under Israeli occupation. To be sure, the struggle on the ground in Palestine began to take center stage. The Oslo Accords presented the PLO with an opportunity to reassert its leadership and get back into Palestine to lead the way forward.

Along with the intifada’s impact on the perceived costs to both the Israelis and to the Palestinian leadership, changing global and regional dynamics helped set the stage for the Oslo Accords. The days of great power rivalry dictating alliances and power balances in the Middle East were over. Washington had succeeded in displacing the Soviets from Egypt more than a decade earlier and Syria was greatly weakened as its patron regime in Moscow was transforming. The secret friendship between Israel and Jordan could not come out into the open; this meant that the threats from regional states to Israel, as they had been conventionally defined over the previous several decades, were significantly mitigated, if not eliminated. In a greater position of power than ever before relative to the Arabs, Israel had no reason not to give peace a chance. At least it could pretend to do so.

Just as the end of the cold war changed Israel’s incentives, so too did the first Gulf War shift enticements for the Palestinian leadership. PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat aligned himself with Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, whose invasion of Kuwait led to an international coalition confronting him, one that included a number of Arab countries. For Palestinians, the fallout was significant. Arab backing of the PLO was weakened and hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were evicted from Kuwait. Financial resources, which were once more readily available to the PLO from the Gulf states, were drying up, and this further limited the options of the Palestinian leadership.

Neither party arrived at the Oslo Accords under ideal conditions and neither agreed to participate fully willingly; rather, they perceived Oslo as the least objectionable of the options. At the time, however, the Palestinians had far fewer alternatives and were much weaker than the Israelis, which meant that the latter were poised to steer the situation in a direction that benefited them most.

The struggle on the ground in Palestine took center stage and the Oslo Accords presented the PLO with an opportunity to reassert its leadership and get back into Palestine to lead the way forward.

The communication exchanges that made the Oslo agreements possible, once they became known, indicated that the Palestinians recognized the state of Israel but that the Israelis only recognized the PLO. The PLO was also pushed to change its official documents over the years leading to the Oslo Accords. In fact, more was consistently asked from the Palestinians than of the Israelis.

It was because of this dramatic imbalance of power at the negotiating table that critics of the Oslo Accords foresaw disaster. Unlike the 1978 Camp David Accords, which turned 40 years old last September 17, the Oslo Accords were not being negotiated between two states. To wit, Soviet-backed Egypt’s ability to inflict significant costs on Israel, most demonstrably in the 1973 war, allowed the Israelis to view a negotiated peace agreement as an alternative to a costly war against an adversary they had to respect. In the Oslo Accords—with the Palestinians a much weaker and stateless people confronting Israel, a powerful state—the power dynamic was very different. Israel was not afraid of its Palestinian adversary at the negotiating table, so it did not view peace talks as a strategic alternative to a costly war. Instead, the accords provided a strategic opportunity for Israel to pursue war against the Palestinians by other means.

A Quarter Century of Morass

The Oslo Accords set up the Palestinian Authority (PA) as a mechanism to work toward the goal of self-determination for the Palestinian people, in line with UN resolutions 242 and 338, while not explicitly committing to statehood. Empowering the PA meant giving it some limited control over territory, starting in the first phase in parts of Gaza and in Jericho in the West Bank. With Oslo II, which followed in September 1995, a much more significant stratification was arranged: the creation of security areas A, B, and C. The Palestinian Authority would assume security and civil responsibility over Area A, which included major Palestinian towns and cities, as well as civil responsibility in Area B. The Israelis would have security responsibility in B and C as well as civil responsibility in Area C. The underlying principle—which doomed the agreement from the start—was the idea that Israeli security superseded the rights of Palestinians. This meant that the rights of Palestinians would only advance as long as Israel felt secure, thereby allowing the latter to veto progress in implementing the agreement at any time.

This became clear at several stages of the Oslo era. During the first term of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, he was able to exploit the definition of security zones in the Wye River redeployment agreement to make progress grind to a halt. He was later caught boasting about this on video.

Later, during the George W. Bush presidency, a revived effort to push for a Palestinian state was based on a document called the Roadmap for Peace; however, this plan maintained the same sequence of principles—Israeli security first, Palestinian rights second. Thus, it prioritized Palestinian Authority reform and elections ahead of everything else. Even though a total Israeli settlement freeze was a first phase obligation, it was never a deliverable that Washington imposed on the Israelis. At the same time, the Americans were fully behind the effort to both marginalize Arafat and force PA succession and elections.

In the Oslo Accords, the power dynamic was very different from that of the Camp David Accords. Israel did not fear its Palestinian adversary and did not view peace talks as a strategic alternative to a costly war.

So valuable was the security-before-progress principle to the Israelis that it was described as the rationale for their withdrawal of troops and settlers from Gaza in 2005. In a lengthy interview in Haartez in 2004, Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s advisor, Dov Weisglass, explained that the logic of the “disengagement” was to freeze the principle in time indefinitely. Terrorism, as he put it, had to be eradicated before there could be a political process; as long as it existed, there was an excuse not to move forward. Indeed, he stated that “The disengagement is actually formaldehyde. It supplies the amount of formaldehyde that’s necessary so that there will not be a political process with the Palestinians.”

In the years that followed, Israel’s siege policies in Gaza have constantly kept the territory on the verge of collapse, all but ensuring continued periods of militancy. No matter what the Palestinian Authority was doing in the West Bank, how many institutions created or new prime ministers appointed, and how deep the security coordination, so long as Israel could point to Gaza it could claim an excuse for not moving forward on the peace accord with the Palestinians.

The security-before-progress framework established by the Oslo Accords was flawed from the outset. What made it even more unviable was that the agreement allowed the application of that principle to the advantage of the stronger party at the table, Israel, instead of insisting that the security of both parties—including the weaker one, the Palestinians—was paramount. This incentivized exploitation instead of commitment and allowed Israel to increase its leverage and deepen its entrenchment in the West Bank, while relieving it of the costs of international opprobrium.

The (in)Decent Thing to Do

Some critics of the Oslo process declared it dead on arrival. Others, including early supporters, have come to the realization over time that the Oslo framework and its associated “two-state solution” have expired, even if they could not point to the exact moment of death. If the decent thing to do with a corpse is to give it a prompt and dignified burial, the opposite is what is taking place under the Trump Administration: dismemberment.

Since taking office in January 2017, officials in the Trump Administration have attacked and dismantled one element of the previous process at a time. They began by attacking the notion of a Palestinian state as a goal then moved on to legitimizing Israeli settlements, “taking Jerusalem off the table,” backing Israel’s demand for a Jewish state by failing to oppose the Nation-State bill, attempting to erase Palestinian refugees and, most recently, taking steps to marginalize the PLO by closing its office in Washington, DC and revoking visas for diplomatic personnel.

In a recent interview, President Trump’s son-in-law and advisor on Middle East affairs, Jared Kushner, said “All we’re doing is dealing with things as we see them and not being scared out of doing the right thing.”

Many would surely disagree with the Trump Administration’s approach, but this is the role Washington is playing now. Twenty-five years have passed since signing the 1993 Oslo Accords and the current White House is determining how to chip away at these accords and their remnants. Sooner or later, however, there will be a day when Trump and his administration will no longer be in power. Anticipating, planning, and preparing for that day—and how a just peace can be achieved—are likely the best options for those who want to make this goal an eventual reality.