Something odd is happening in oil markets. Demand is weaker than it has been in many years, yet OPEC+ is unwinding cuts and increasing production at a brisk pace. Some 2.2 million barrels per day of extra OPEC crude could return to the market by next September. As a result, prices—which had been sitting between $70 and $90 a barrel—have started to slip. Falling oil prices are coming alongside unprecedented Saudi investment in economic diversification, led by the trillion-dollar Neom project. The “breakeven” oil price needed to cover Saudi government spending has risen to $96 per barrel, which begs the question: why would Saudi oil market strategists approve a policy that reduces government revenue?

The answer lies in the complexity of the oil market. OPEC decisionmakers balance the economic welfare of member states with other factors, including geopolitical risk, the interests of importing states, and the competition between oil and substitutes like batteries. Diplomacy and geopolitics have lately gotten volatile, with wars in the Middle East and an unpredictable US president in the White House.

At the moment, the stars are aligned for a major shift in strategy. Even with the Saudi budget headed for a big deficit, eight countries of the OPEC+ cartel—Algeria, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Oman, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—are rolling back, or unwinding, cuts that are set to end in 2026. These countries have begun suspending cuts of some 2.2 million barrels per day (bpd) last April while the rest of the OPEC+ countries are continuing with theirs. Oil prices, and Saudi revenues, could well fall further.

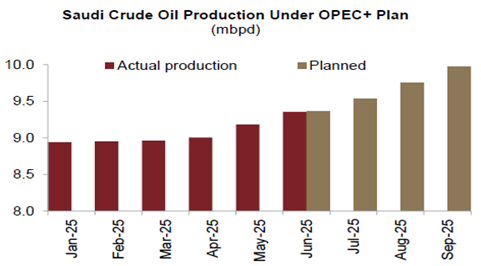

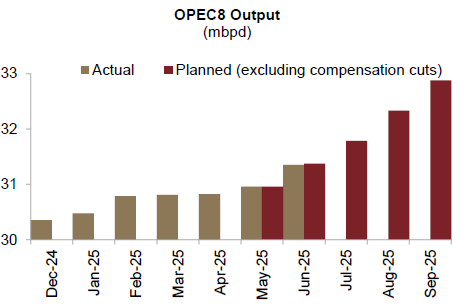

OPEC’s main eight members are ramping up production.

Quota Cheaters Lead by Example

What is the rationale for unwinding now? Perhaps the strongest reason is that OPEC’s hand is being forced by “cheating” member states that have raised production unilaterally. In other words, more oil would be coming to the market whether or not OPEC gives its blessing.

Kazakhstan, where production has increased by 400,000 bpd in recent months, is a case in point. Chevron has just finished a 260,000 bpd expansion of the Tengiz oilfield. The American oil major and the host government were obviously not eager for the project to languish. The Kazakh government had grown recalcitrant, ignoring its OPEC+ quota and even the cartel’s demand for “compensation” cuts as penalties for prior overproduction.

The UAE is another member chafing under OPEC’s restrictions and is finishing its own multibillion-dollar capacity expansion, moving from 3 million to 5 million bpd. Abu Dhabi’s oil production capacity now stands at 4.85 million bpd, but until recently the UAE’s quota restricted it to 2.91 million bpd; practically, the quota was idling 40 percent of capacity. The disproportionate penalty brought talk of the country quitting OPEC. Further quota overages have been documented in Iraq and Russia.

Untenable quotas meant group cohesion was fraying and the cartel’s remarkably resilient discipline began to falter. In one way of looking at the ongoing rollbacks, the cartel is simply getting out of its own way.

Twelve Days of Geopolitics

There are other factors at work as well. Israel’s June 13 attack on Iran—joined by the United States on June 21—triggered a 12-day war in the world’s most oil-rich region. Beyond the death and destruction caused, mainly inside Iran, the war created huge uncertainties in the oil market. Oil prices jumped from $64 to $79 a barrel. That $15 bump is relatively modest compared with what might have happened if Iran had tried to close the Strait of Hormuz and choke off the oil and liquefied natural gas exports that traverse it, which constitute roughly 20 percent of the global supply of each.

Twelve days of war on Iran created a strong rationale to bring more OPEC oil to market.

Still, 12 days of the Israeli-American war on a founding member of OPEC created a strong rationale to bring more OPEC oil to market. The Trump administration was eager to prevent the war from bleeding deeper into oil prices and upsetting US producers. Keeping a lid on prices was the lack of any Israeli or American bombardment of Iran’s main oil export terminal at Kharg Island. Israel attacked oil storage sites and offshore gas production, but Iranian oil exports continued during the war.

Despite the United States joining the Israeli war, US enforcement of President Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” sanctions appeared to ratchet down after the ceasefire of June 24, 2025. Iranian oil was flowing to markets at the time of writing, with exports increasing slightly in July.

The Russia Question

Another factor signaling a loosening of OPEC quotas is the Trump administration’s threat to choke off some of Russia’s oil exports which have already declined modestly since its 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Russian oil has been all but displaced from embargoing Europe and now flows mainly to Asia.

As the second largest oil exporter in the world—shipping about 7.25 million bpd in June—the loss of Russian supply could create market havoc. Most Russian oil goes to China and India, followed by Turkey. Trump has imposed a 50 percent tariff on US imports from India, aiming to persuade New Delhi to cut its imports of 1.5 million bpd of Russian oil. US tariffs on Turkey were also bumped to 15 percent, perhaps in response to Ankara’s imports of 900,000 bpd of Russian oil. Clampdowns on Russian exports could have a big short-run effect on prices, another great reason for OPEC to raise production.

Of course, chasing Russian oil from India and Turkey would not bottle it up forever. Discounted crude oil would find its way to market, further bolstering the dark shipping fleet that evades tracking attempts. Even so, the potential for declining supply gives OPEC the opportunity to step up with additional production.

The Price War Is a Necessary Evil

Another reason to adjust OPEC’s focus from “price hawkishness” to “recapturing market share” is the necessity of periodically making such a shift. The fact that OPEC is sitting on so much unused production creates temptation for competing producers. High oil prices incentivize more investment in non-OPEC oil. And the onset of more non-OPEC oil negates the need to bring back OPEC’s idled production.

To prevent permanent loss of market share, OPEC periodically needs to reopen the taps and give high-cost producers “a good sweating,” as John D. Rockefeller once said, to limit their access to the market and impact on it.

Such increases—often called a “price war”—demonstrate that OPEC has a credible tool of punishment for either low-cost producers who do not consistently join in Saudi Arabia’s sacrifices (i.e., “cheaters”), or for high-cost producers who take advantage by ramping up output.

US shale production, with costs far higher than those of Saudi Arabia or Russia, has benefitted greatly from the kingdom’s constraints on oil production. Shale is first in the OPEC targeting line. The United States is already producing some 13.3 million barrels of crude oil per day—more than any other country in history. OPEC officials said they wanted their relaxed quotas to inject “a lot of uncertainty” into investment plans in the United States.

It is not just American oil. OPEC wants to deter ambitions everywhere. Big announcements of investments or new discoveries of oil in Brazil, Somalia, Suriname, and Namibia are also threats. By flooding the market and pushing down prices, OPEC can push returns on high-cost projects into negative territory or—better yet—discourage future investments by raising doubts about long-run prices.

Also, some OPEC members have been unable to ramp back up to their new production levels, which means that quota increases have not been met with corresponding crude flows. This suggests that Saudi strategists could allow further production increases among OPEC members with wherewithal to do so.

The Trump Factor

If OPEC wanted to make President Trump happy, raising oil production would be a good bet. The US president has also injected himself into the oil trade, providing policy favors to American oil companies that supported his campaign, while calling for OPEC to bring prices down. OPEC is now doing exactly that, which is great for US drivers, but not so great for US producers. One example of Trump’s oil price pressure came in April, just ahead of his May trip to Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE. While OPEC officials denied claims of appeasement, analysts suggested the claims might be valid.

Trump’s tariffs are one of the culprits of weaker-than-expected oil demand.

Regardless of whether Trump influenced decisions in OPEC headquarters in Vienna, being seen as amenable to suggestions from the US president is generally a good outcome for OPEC. In May, after the president’s Mideast trip, the White House took credit for lower gasoline prices. Of course, lower oil prices mean that the grandiose promises made by leaders of the UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia for $2 trillion in investment in the United States look even less likely to materialize.

Further, Trump’s tariffs are one of the culprits of weaker-than-expected oil demand. The International Energy Agency (IEA) data show that, in the second quarter of 2025, the biggest declines in oil demand took place in countries targeted by US trade tariffs: China (hardest hit), Japan, South Korea, and Mexico.

Timing Suggests Brevity

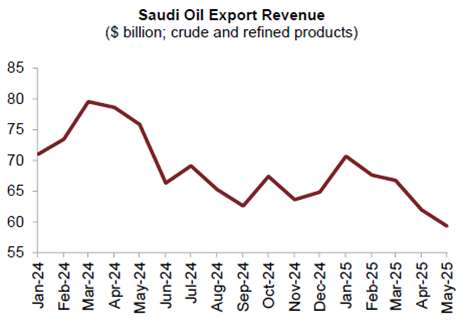

The timing of OPEC’s production increase is not ideal for Saudi Arabia’s capital investment programs. The kingdom needs more cash—not less—for its ambitions to create new economic sectors in tourism, real estate, mining, ports, and high-tech manufacturing. Declining oil prices mean those plans will have to be delayed or scaled back.

The fiscal needs of Saudi Arabia point toward a lukewarm embrace of OPEC’s current “market share” strategy and portend a return to maximized prices as soon as possible.

Saudi oil production is going up and oil revenues are going down.

Capital needs in the kingdom are immense. The cornerstone of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 is to diversify its economy beyond oil by attracting over $100 billion in annual foreign direct investment to fund massive “gigaprojects” like NEOM and Qiddiya. Moreover, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s (MBS) $1 trillion investment “promise” to the United States will require more oil revenues.

Riyadh has also had difficulty attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). Current trends have shown FDI flows to the kingdom increasing since 2017 but reaching only a fraction of the 2030 goal. For 2023, inward FDI reached $25.5 billion, or 2.4 percent of GDP, which was down slightly from the annual average of $30 billion in 2021-23.

As a result, Saudi Arabia has been forced to self-fund its economic transformation via bond sales and selling stakes in government-owned firms, including Saudi Aramco. The enormous scale of the Vision 2030 agenda—the center of which is building the city of NEOM whose cost is estimated at anywhere between $500 billion and $8.8 trillion—is beyond even the means of the kingdom’s sovereign wealth funds. This situation contrasts with that in the UAE and Qatar, where exports of energy commodities—relative to government outlays—leaves them with billions of surplus dollars earmarked for overseas investment, including in the United States.

One recent report said that the Saudi Public Investment Fund was looking to find ways to reduce investment outside the kingdom, including MBS’s $1 trillion commitment to the United States. Executives from international investment and advisory firms were privately questioning Riyadh’s ability to finance its commitment and viewed it as a headline-generating attempt to win the Trump administration’s favor.

All these negative news and conditions suggest that OPEC’s shift in market strategy will soon be reassessed.

Conclusion

For oil exporting countries, the belt-tightening required in reclaiming market share is partly offset by other benefits. OPEC’s actions to push down oil prices protects long-run demand for oil and maintains oil’s price advantage over alternate fuels and technologies. This is important in an era when prices on batteries and solar panels are declining so quickly that solar-powered vehicles could soon be cheaper to operate than gasoline-powered cars.

By contrast, Middle Eastern oil producers are sitting on proven reserves that can produce at current rates for 83 years on average. The figure for Saudi Arabia is 74 years. To prevent stranded reserves—unused production capacity—these countries need OPEC to promote oil’s attractiveness, even in the face of a worsening climate. Lowering prices is the most effective way, despite the short-term economic downside.

It is also the only way for the dominant oil producers in OPEC to scare off the threat of alternate supplies in the market. The Saudis have launched price wars many times before, most recently during the COVID pandemic in 2020, when Russia refused to cut production. It had fought a similar war in 2014, when OPEC members refused to act. This time around, the reasons are more diverse, but are just as compelling.

The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.