On May 6, Lebanon will hold its first legislative elections since 2009 that will rearrange the country’s political landscape. Under new rules and gerrymandering, these general elections will merely redraw the representation of powers of the same ruling class. They are expected to reinforce the alliances of the 2016 deal that elected General Michel Aoun President following nearly two and a half years of vacuum at the top of the executive branch.

The executive branch serves basically as an extension of the legislative branch’s power distribution.

The election law, adopted last June after a long impasse, is the blueprint for this popular vote. The redrawing of political boundaries reduced the number of electoral districts to 15, down from 26 in the 2009 elections. Several reform measures included in this electoral law were not enforced, including the magnetic card for voting; however, the use of official preprinted ballots for the first time ends a controversial election fraud tradition in Lebanon. Also for the first time in the history of Lebanese elections, voting will be held based on the proportional instead of the majoritarian system. Voters will have to select a list across sectarian representation, but they will also have the option to choose a candidate as their “preferential vote.” These changes were primarily meant to address the concerns by Christians regarding their ability to elect their own representatives instead of having the latter piggyback on lists led by Muslim candidates. The “preferential vote” allows minority Christian voters in predominantly Muslim districts (and vice versa) to choose their own representatives.

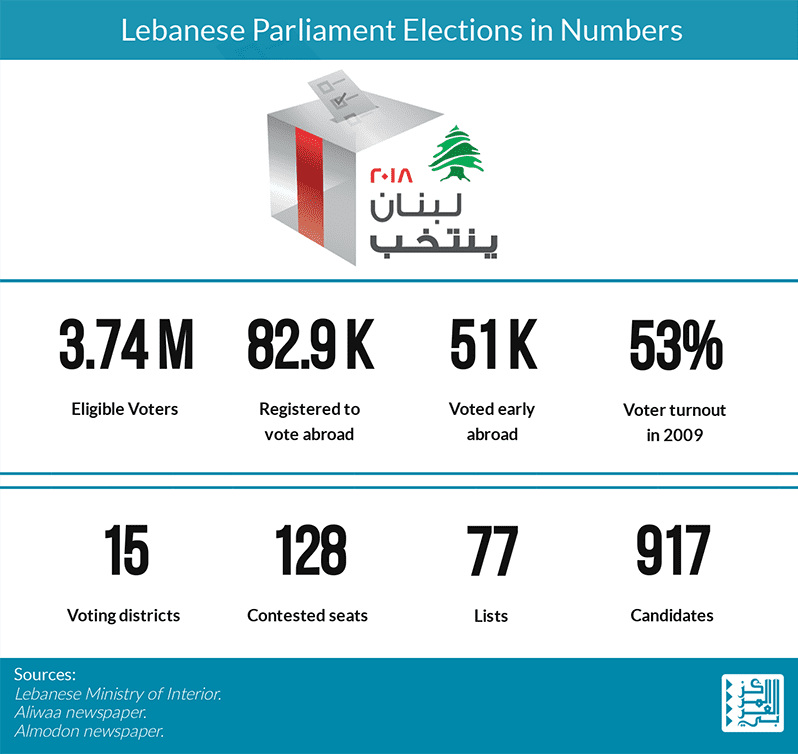

To be sure, these elections illustrate the extent of control confessional leaders have over the political system. In a sense, the parliament in Lebanon is less about legislative accountability; the executive branch serves basically as an extension of the legislative branch’s power distribution, which impedes the separation of powers and the system’s checks and balances. Sixteen of the 30 cabinet ministers are running as candidates for parliament, including the interior minister Nohad Machnouk who oversees the organization of these elections. Table 1 below illustrates the number of voters, districts, seats, and candidates in the upcoming elections.

Table 1:

Political Trends Influencing the 2018 Elections

There have been momentous changes in Lebanon and its neighborhood since the legislative elections of 2009. Regionally, between 2011 and 2013 as the uprising in Syria turned into a civil war, sectarian tensions increased between the Sunni Future Movement, led by Prime Minister Saad Hariri, and the Shia Hezbollah, led by its Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah, as the latter group joined the fighting next door in Syria. In 2014, these two major political parties began talks to contain these tensions, which stabilized the security and political situation in Lebanon. The Saudi Arabian king, Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, assumed power in January 2015 and two months later his son, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, launched a war in Yemen, ostensibly as part of a push against Iranian influence in the region, including Lebanon. This Saudi campaign reached its peak in November 2017 when Hariri was forced to resign in Riyadh, in an apparent attempt to replace him with a hawkish Sunni leader ready to confront Hezbollah.

The electoral alliances reflect the relationships among the ruling class, and the ambiguity of the regional situation.

Domestically, during the presidential vacuum between May 2014 and October 2016, structural shifts occurred in the alliances between Lebanese leaders. Hariri had long resisted the idea of electing Aoun as president, considering him Hezbollah’s candidate, while Aoun would not have had enough votes to win without Hariri’s large parliamentary bloc. Aoun reconciled with his Christian arch rival, Lebanese Forces leader Samir Geagea, and forged a strong bond with Hariri, which eliminated a major domestic barrier to his election. However, Saudi Arabia was not quite ready for a compromise with Iran and kept a veto on electing Aoun. With American and Iranian consent, the presidential deal ultimately passed and Aoun became president in October 2016. The synergy between Aoun and Hariri subsequently became clear and was reinforced after Hariri’s forced resignation last year. The United States and France intervened to preserve this presidential deal, prompting Hariri to rescind his resignation upon returning to Beirut.

Electoral Alliances and Predictions

The Lebanese elections will be held against this background. The electoral alliances reflect the complexity of the electoral law, the vulnerable relationships among members of the ruling class, and the ambiguity of the regional situation. It is safe to argue that the winners of 70 percent of the seats are likely going to be predetermined due to the confessional nature of the political system, so the competition will be reflected only in the remaining percentage.

There should be no surprises, for instance, in the Shia vote as the two main political parties, Hezbollah and the Amal Movement, are united in their efforts and will secure a combined number of 25 seats. The Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), currently led by President Aoun’s son-in-law and foreign minister, Gebran Bassil, should maintain the majority vote among Christian voters, though the Lebanese Forces political party is making headway. It is worth noting that nearly 12 years after their alliance, the only meaningful electoral partnership between Hezbollah and the FPM in the 2018 election is in the Baabda district (Mount Lebanon), a symbolic area where the two political parties signed a memorandum of understanding in 2006.

While electoral alliances vary from one district to another, depending on demographic and political factors, the most significant alliance is the one between the Future Movement and the FPM, which in effect is found in the most competitive constituencies in Zahle, Beirut, and North Lebanon. The new electoral law and the “preferential vote” encourage the candidates competing from the same sect to run against each other, which explains the numerous lists in important cities like Beirut, Zahle, and Tripoli. The 2018 elections are also witnessing a growing number of lists and candidates outside the mainstream ruling class, as activists and influencers are running for office and hoping to emulate the success of getting 40 percent of the vote during the 2016 municipal elections in Beirut. While they have successfully formed lists across Lebanon’s 15 districts, these groups and individuals (loosely defined under the civil society umbrella) remain divided in their platform and outmaneuvered by a ruling class with significantly better resources. Far from being effective in a confessional system, these efforts are the first serious attempt in decades to break the glass ceiling of the ruling class.

The two mainstream leaders who are expected to lose the most in 2018 as compared to 2009 are Saad Hariri and Druze leader Walid Joumblatt. The majoritarian system and the previous districting allowed them to have large parliamentary blocs that included Shia and Christian representatives. They are set to lose these seats on May 6. Hariri faces fierce competition in Beirut’s second district, where a high number of nine lists and 83 candidates are competing for 11 seats; however, he is expected to score a victory in his stronghold. Sunni rivals are also challenging Hariri’s candidates in Tripoli, in North Lebanon, where the Lebanese premier’s national leadership in the Sunni community will be tested (a high number of eight lists are competing, while the national average is four lists per district). The competition between Hariri and Joumblatt over seats became apparent in recent weeks, as the Lebanese premier removed1 Joumblatt’s candidate from their joint list in the western Beqaa, which led to friction between the two allies. As Joumblatt’s parliamentary bloc is shrinking, Hariri is prioritizing his alliance with the FPM instead.

If regional dynamics are meant to have impact on Lebanon, the country’s stability that has been assured since 2014 will be at risk.

The most likely outcome in this new parliament is a parliamentary bloc led by the Future Movement-FPM, which emulates the 2016 presidential deal, versus an opposition parliamentary bloc led by the Shia coalition and Joumblatt. These alliances are opaque and can shift depending on the issue at hand and the interests of foreign backers. Meanwhile, the election campaign rhetoric of these major political parties reflects their tactical approach.

Hezbollah has been emphasizing the unity of the Shia coalition, the religious obligation of voting, and the preservation of its resistance against Israel. Hariri is returning to some of the May 2008 rhetoric when the Future Movement clashed with Hezbollah in the streets of Beirut. The Lebanese premier has affirmed2 that those who are running against him and those who are staying home on election day are casting a vote for Hezbollah. Hariri and his movement are also calling out opponents known for backing the Syrian regime in the past. However, the ruling class candidates seem inclined to avoid political tensions and share a tacit understanding that election campaigns are about playing into the base before going back to business as usual on May 7.

The elections in Lebanon are being held in a volatile regional context as an Israeli-Iranian confrontation is looming, especially in light of President Donald Trump’s possible decision to scrap the Iran nuclear deal. If these new regional dynamics are meant to have impact on Lebanon, the country’s stability that has been assured since 2014 will be at risk no matter the election outcome on May 6. The 2016 presidential deal reinforced the international community’s decision to stabilize Lebanon regardless of regional dynamics. The political struggle between the Lebanese ruling class should remain within this context; indeed, Lebanon has experienced enough regional adventurism.