In June, Jordan’s King Abdullah II appointed a 92-member commission, headed by former Prime Minister Samir Rifai, and charged it with creating a plan to modernize the elections in Jordan and the laws governing political parties. The commission is to submit its proposed laws to the king by November, after which they would be discussed and passed by the government and then taken to a vote in parliament. While the king did not make any specific recommendations, the commission could very well initiate an ambitious ten-year plan that could result in a constitutional monarchy, after a little over two decades of the monarch’s accession to power. The longest reigning current Arab leader, the king has learned that what is needed to make change is more than a mere decree from the palace or a well-written directive. Indeed, the king has published seven discussion papers that have largely gone unnoticed. What is required is a mechanism that can attract public buy-in.

Many may see this latest effort by King Abdullah as yet another exercise in obfuscation and fake reform without any intention of carrying out meaningful political change in the kingdom. But there are at least two facts that contradict such thinking. First, the size and composition of the Royal Committee to Modernise the Political System points to the seriousness of the effort. The commission is truly representative of the political, religious, ethnic, and ideological mosaic of the Kingdom of Jordan. Second, neither the government, the palace, nor the security services have interfered in the committee’s work so far or attempted to control the outcome of its deliberations. The commission includes Islamists, leftists, pan-Arabists, conservatives, liberals, genuine democrats, and tribal leaders. Many of the members have thick security files and have had plenty of visits to the mukhabarat (Jordan’s powerful intelligence service).

Naysayers are plenty, and with good reason and evidence. Previous reform efforts have failed to produce real change. Defenders of the king say he was always a reformist but his opponents hobbled and derailed the process. This time around, it appears there is more serious effort from the top of the pyramid and the process seems to be moving in a positive direction. According to members of the royal committee, the discussions have been serious and genuine and have sought common ground. Perhaps Rifai’s presence and role—he is a friend and confidante of the king—provided the commission members with the confidence that Abdullah has a genuine desire for reform.

Why Now?

Some argue that the “sedition” case of April 2021 and the sudden popularity former Crown Prince Hamzah has garnered from a wide range of Jordanians are a major impetus for the change at this time. The argument is if King Abdullah plans to pass the baton to his son, Hussein, he must prepare the groundwork necessary for the succession. A serious and open power-sharing mechanism must be set forth to allow the young crown prince to be able to rule in the capacity the people eventually choose. But for this to take place, there have to be laws that undergird the process of political development in the country—and specifically, one law that governs free elections and another that regulates political parties.

A serious and open power-sharing mechanism must be set forth to allow the young crown prince to be able to rule in the capacity the people eventually choose.

The process that was instituted by the new commission allows it to produce agreement on the text of the two basic laws for elections and parties, which will then get the king’s blessing and the approval of the current government headed by his confidante, Bisher Al-Khasawneh. Then, with enough votes in the current parliament, it would be approved. In a sense, this would amount to a self-inflicted wound for current parliamentarians who won their seats according to a different and soon-to-be abandoned formula.

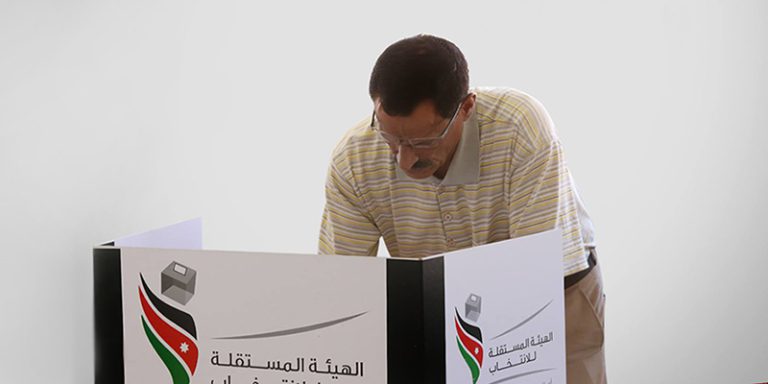

On more than one occasion—and when confronted with a national policy dispute—the king has insisted that for major decisions, change must come from the bottom and up. In fact, the Jordanian version of the Arab Spring in 2011 provided an opportunity for change. The king welcomed the peaceful protests and the Jordanian police was even filmed1 distributing water bottles to demonstrators. Constitutional reforms were made, although they were relatively moderate; these included the formation of a constitutional court—albeit restricted in who can appeal to it (the government, the parliament, or the courts)—and an independent elections commission.

But the small gains of the Arab Spring have quickly evaporated as the intelligence service’s power grew, in part because of the internal and external threat from the so-called Islamic State. Jordanian authorities are apprehensive about the reach of the organization, especially because of the current economic challenges facing the country.

Proposed Changes

The current law regulating political parties did little to encourage program-based parties that would compete for parliamentary seats and a chance to govern. Forty-nine parties are currently registered in Jordan, but only the Islamic Action Front—an affiliate of the Muslim Brotherhood—has succeeded in making a dent in the political landscape. Political parties are not allowed to operate on college and university campuses and the security services often harass party members and their benefactors. Without national parties, the electoral law, which is based on the principle of one-person, one-vote, produced loyal individuals, most of whom wanted to reach parliament so that they could improve their own positions and provide perks to their families and close friends.

The commission was off to a bad start when two of its members were forced to resign and their resignations were accepted by commission head Rifai.

The commission was off to a bad start when two of its members were forced to resign and their resignations were accepted by commission head Rifai. It began with the accusation of one member, Oraib Rantawi, of disloyalty to the Jordanian army. Rantawi, a Jordanian of Palestinian origin, has a daily column in which he compared the decision-making mechanism of the late Yasser Arafat with that of the current Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas. One of his examples was the Battle of Karameh in 1968 when the Israeli army was repelled during an attempt to enter the East Bank town of Karameh. Rantawi was criticized by army loyalists for failing to mention the role of the Jordanian army in that battle. And despite a long explanation by Rantawi and praise of the Jordanian army, the attacks on him on social media continued and he finally had to resign.

Another member, Professor Wafa Abu Khadra, made a comment on her Facebook account about the cruelty of slaughtering and sacrificing sheep during the al-Adha religious celebration. Islamists were up in arms and attacked her commitment to the tenets of Islam. She, too, had to resign. Opponents of the royal commission also started to dig for dirt on other members to discredit them. The chair of the commission and the prime minister finally intervened publicly and even provided discreet bodyguards to some of the targeted members. The deliberations were allowed to continue.

Some might argue that the attacks on the commission are probably the best proof that what members were telling the press included an element of truth, that the commission was given a free hand and that they were making groundbreaking changes. Independent local media quoted and even published entire drafts2 of the committee’s deliberations, which it permitted. Various members of the commission spoke to the local press about the direction that they were taking in their discussions.

It was decided that a constitutional monarchy would be instituted within a decade, and in that framework the nationally elected members of parliament would form a government. This is compared to the current order in which the king has the constitutional power to appoint and fire a government. The election subcommittee approved3 an election law that, among other things, provided the following: 1) gradually increasing party representation in parliament; 2) forming national and local lists; 3) lowering the eligible age for candidates to 25 (from 35); 4) requiring a threshold of 3 percent for winning seats; 5) cracking down on dark money that corrupts elections; and 6) continuing the quota for women and minorities.

The political party4 subcommittee made it illegal for anyone to hinder the work of parties in universities. It raised the number of minimum registered members to 1,000 in order to be licensed, among them 20 percent women and 20 percent youth. It also shifted the registration of parties to the Independent Election Commission instead of the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Political and Parliamentary Affairs and made it a crime for any party to show support to a terrorist or to a takfiri party or movement that espouses extremist political and social views.

Questions of Representation

One of the reasons for the decade-long changes appears to be the biggest stumbling block in the entire reform effort: the demographic equation. The current parliamentary seat distribution greatly favors rural areas that have a high East Bank and tribal population, while the much larger numbers of major city dwellers are Jordanians of Palestinian origin who have been granted fewer seats in comparison to their size. For example, the ratio of voters to the number of seats in the large cities of Amman and Zarqa is many times higher than that for the Bedouin communities and the southern town of Tafila.

Amer Bani Amer, the director of Hayat Center whose RASED program has been studying the seat distribution for years, told the author that some changes regarding this issue will take place: “While we were unable to make huge changes in this area, we overcame a number of problems where clear gerrymandering was taking place.” Amer, who is the rapporteur for the election law subcommittee, said that in some districts the imbalance was fixed by combining districts like in Zarqa and Amman without losing representation.

These changes will not fully address decades-long biased seat distribution; however, combined with the increase in national votes, where all Jordanians will have an equal chance to compete, this built-in bias can be gradually addressed.

The Road Ahead

When the current process began, few people had the confidence that it would spur any changes; they felt that in the end, it would fail. These recommendations, which will be delivered to the king and will still need to go through the parliamentary process, provide hope that Jordan might be moving in the right direction. The effort will no doubt face obstacles along the way. In the unstable Middle East, no one can predict whether a small country with limited resources could make a democratic leap to a constitutional democracy. The fact that the royal commission has given this process ten years and has provided a detailed roadmap to get there shows that this is not merely wishful thinking, but that it has the seriousness of a new strategy.

The effort will no doubt face obstacles along the way. In the unstable Middle East, no one can predict whether a small country with limited resources could make a democratic l leap to a constitutional democracy.

Will this process work and turn the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan into a constitutional monarchy, like the United Kingdom or Sweden? Based on all indications so far, a wide-ranging representative group of Jordanians has reached consensus to take a confident leap of faith in that direction. The question still remains, will this be the bottom-up process that the king desires?

Daoud Kuttab, an award-winning Arab journalist, runs the Community Media Network in Amman, Jordan. He is the former Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton University. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC or its Board of Directors.

1 Source is in Arabic.

2 Source is in Arabic.

3 Source is in Arabic.

4 Source is in Arabic.