After weeks of anticipation and political maneuvering, on December 26, 2018 the Israeli Knesset formally voted to dissolve itself, thus allowing early elections to take place seven months before the completion of the full four-year term provided by law. “The bill for the dissolution of the 20th Knesset,” according to the Knesset website, “passed by a vote of 102-2 in its third (final) reading.” It “also sets early elections for April 9, 2019.” The political editor of the Jewish Journal, Shmuel Rosner, writes that the campaign “is going to be short and fierce. Three months plus small change. Netanyahu has the edge, but legal troubles can complicate his situation.” Polls show 35-40 percent of Israelis preferring Netanyahu as prime minister, while 28-30 percent favoring the newcomer, former Chief of Staff Benny Gantz, for the job.

Election campaigns in Israel’s fractured coalition system are normally quite contentious and full of surprises. The 2019 early elections scheduled for April 9 are not an exception. Indeed, considering the fiercely competitive agendas, intense political environment, and irreconcilable differences between the candidates, the campaign promises to be a brutal bloodbath, even by Israel’s usually divisive and highly spirited standards. As the Knesset opened the starting gate, different candidates and party blocs were off at full speed jockeying for a favorable position in the race. The first victim of political cannibalism was former Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni of the Hatnuah Party, whose alliance with Labor was unceremoniously annulled on live TV by Labor Party chairman Avi Gabbay.

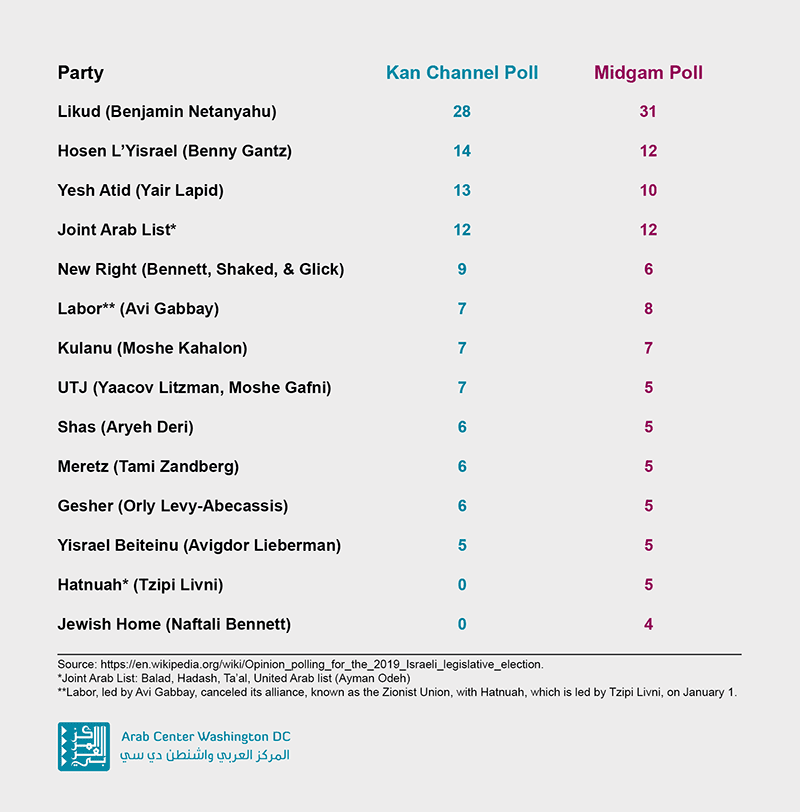

The 2019 Parliamentary Lineup for the 21st Knesset

Typical of all coalition governments, Israeli elections tend to be very complicated and crowded, requiring multiple political parties or blocs to cooperate and pool their resources together to form a coalition government that none can produce on their own. The following table lists the current lineup among existing political parties as of January 2, 2019 and their prospective seats in the next Knesset, according to two separate pollsters:

These poll results clearly indicate that Israel will remain governed by a political coalition on April 9. The most likely candidate to form such a coalition government would be the right-religious camp led by Benjamin Netanyahu, if it manages to attract a centrist party or two to join it as partners in securing parliamentary majority. The left—or whatever is left of it—may attempt to do the same, but it would face an improbable statistical challenge of winning a simple majority of 61 seats in the Knesset—something it cannot do without striking a deal with the Joint Arab List that comprises the main Palestinian Arab parties, a development that would not be tolerated by the current and predominantly racist public opinion in Israel.

Why Did Netanyahu Opt for Early Elections?

There are several reasons that convinced Netanyahu to pursue early elections in April. They include the shaky economy, his diminishing parliamentary majority resulting from the resignation of former Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman on November 14, the weak state of the opposition, and the potential launch of Trump’s long-awaited Middle East peace deal, all of which made the notion of early elections more appealing and advantageous to the prime minister. However, Yossi Verter, senior political writer and commentator for the Israeli daily Haaretz, insists that the multiple legal cases Netanyahu is facing pertaining to bribery, graft, and corruption served as the trigger that prompted the prime minister to seek early elections. “It’s the investigations, stupid,” he argues. Verter claims that “Once the State Prosecutor’s Office determined that Netanyahu ought to be indicted, the premier realized he was facing elections.” Frankly, Netanyahu, who still denies any wrongdoing, might have a point here; after all, facing parliamentary elections that he has a reasonable chance of winning is a more attractive option than the prospect of being reduced to a defendant facing potential resignation and/or jail time.

For Netanyahu, facing parliamentary elections that he has a reasonable chance of winning is a more attractive option than the prospect of being reduced to a defendant facing potential resignation and/or jail time.

The legal cases against Netanyahu are not new at all. Some of the charges leveled against him date back to 2014-2017 when he served as prime minister and communications minister in a previous government. However, what happened on December 19 prompted Netanyahu to take his potential indictment seriously by rushing his election gambit to avoid criminal charges. State Prosecutor Shai Nitzan made public at a conference in Tel Aviv that sufficient evidence exists against the prime minister to recommend his indictment for bribery charges in the three cases known as “Case 1000,” “2000,” and “4000.” The news was quite alarming for Netanyahu and his advisors once they realized that the state prosecutor and attorney general had no option or intention of dropping all three cases for fear of being accused of meddling in the elections. Netanyahu is clearly facing a serious legal situation with at least one potential bribery charge; this prompted him to advance the elections date, hoping to pressure Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit to postpone his indictment until after the elections.

Netanyahu is clearly facing a serious legal situation with at least one potential bribery charge; this prompted him to advance the elections date, hoping to pressure Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit to postpone his indictment until after the elections.

Although Netanyahu denies it, insisting that the “security of the nation is beyond politics, and the security of the nation is beyond personal concerns,” the prime minister feared that a public indictment on the eve of the elections would force him to resign—a prospect he would like to avoid at any price. Therefore, he felt more at ease putting his case before the voters instead of a judge in a court of law. In other words, Netanyahu sought protection from the law by appealing to voters. Former Director General of the Mossad Shabtai Shavit tweeted1 on January 1, 2019, that Netanyahu was overheard stating, “Whoever decides whether I will continue to serve or not, that is the voter and not the law.”

The Implosion on the Israeli Left

The Israeli left has been undergoing a political free fall for more than a decade; the party bloc has been reduced to a mere shadow of its former self. The current disarray in the center-left camp came to a head on January 1 with the awkward and surprising collapse of the Zionist Union as Labor split from Hatnuah. This rendered their separate challenge to Netanyahu insignificant, with some pollsters even doubting the ability of Tzipi Livni’s Hatnuah to pass the qualifying electoral threshold currently set at 3.25 percent of all eligible votes cast. The rift has far-reaching implications for the future of the parties involved and for the outcome of the upcoming elections. Subsequent poll results were quite unkind to both, predicting a steep drop by Labor to seven or eight seats only, placing it in sixth place in terms of the number of seats held in the next Knesset. If Hatnuah, led by Livni, manages to pass the threshold, it is forecast to win five seats, at best.

Unsurprisingly, Gabbay’s humiliating treatment of Livni was not well received by Labor Party members, whom he failed to consult. Jonathan Lis wrote in Haaretz that party activists blame Gabbay for ignoring vital “security and diplomatic issues,” which resulted in “the party’s drop in the polls.” Some critics within the party embarked on collecting signatures calling for his resignation without proposing a credible replacement as party chair, at this late stage in the game. Yossi Verter accused Gabbay of driving “a final nail in his party’s coffin,” thus fulfilling a decade-old prediction by the late Israeli novelist Amos Oz that the Labor Party had “completed its historic mission.” On the other hand, Gabbay blamed the breakup on Livni’s unwillingness to commit against joining a coalition government under Netanyahu’s leadership. However, they both failed to understand, according to a Haaretz editorial, that “Opposition parties that squabble and eat into each other’s electoral support serve Netanyahu and the right, which is united around one leader.”

The remaining parties deemed as left of center—the Joint Arab List and Meretz—will maintain their current power base, winning 12-13 seats and 5-6 seats respectively. However, their direct role in the next coalition government and overall impact on it will remain negligible due to their marginalization by the mainstream parties. Yet despite their vulnerability, divisiveness has even spread to the Arab parties. On January 8, Dr. Ahmad Tibi, a prominent Palestinian lawmaker representing Ta’al in the Knesset, requested to part ways with the Joint Arab List over seat allocation within the group. In addition, other members of the Arab coalition have opted not to run for office in April, including Dov Hanin of Hadash and Hanin Zoabi and Jamal Zahalka, both members of Balad. It is premature at this time to determine whether the Joint List will be able to win 12-13 seats in the 21st Knesset.

The role of the Joint Arab List and Meretz in the next coalition government and overall impact on it will remain negligible due to their marginalization by the mainstream parties.

Considerable Infighting on the Right

Acrimony and divisiveness are not limited to the leftist camp in Israel. Parties on the right are also maneuvering to improve their share of the spoils in the upcoming elections and beyond, should Netanyahu be forced to resign or not run for office altogether. Although Likud remains the largest party in the Knesset with potential to win more than a quarter of the Knesset seats in April, the most dramatic split thus far was taken by former Likudniks Ayelet Shaked and Naftali Bennett, two ambitious right-wing ideologues with no love lost for Netanyahu. After repeated denials of their intentions, Shaked and Bennett submitted their resignation from Habayit Hayehudi (The Jewish Home) and launched, together with Breitbart and Jerusalem Post columnist Caroline Glick, their new party Hayamin Hehadash (The New Right). Bennett portrays his new party as “still a right-wing party, but not extreme,” with a broader, slightly more secular and less pro-settler agenda than his earlier national-religious platform. The New Right is not forecast to supplant the Likud, but it could win six to ten seats in the 21st Knesset, enough to guarantee its continued role in the governing coalition under Netanyahu. These developments left the political future of Habayit Hayehudi somewhat unsettled, with the possibility of dropping to four seats in the next Knesset.

The division on the right is quite relevant as Israeli political analysts begin to view the April elections as “right vs. right” rather than “right vs. left.”

This division on the right is quite relevant as Israeli political analysts begin to view the April elections as “right vs. right” rather than “right vs. left.” As Gideon Levy recently wrote, in Israel “There’s no left, not even half a left. There is only a right, in different forms.” He described the current political system in Israel as “Right A versus Right B, a split in Right C, a possible merger in Right D, and a new glimmer of hope in Right E.”

Levy indicated in the same article that most Israeli political leaders are former Likudniks, including Tzipi Livni, Avi Gabbay, Avigdor Lieberman, Ayelet Shaked, Naftali Bennett, Moshe Ya’alon, and Moshe Kahlon. And regardless of their current party affiliation, Levy argues, “Right, center, supposed left—they all came out of the Likud. And that’s no surprise—the right was their home and it remains their home.” Levy’s perspective might sound too radical or farfetched for some; however, his assessment of the current political map in Israel is borne by how various parties have handled a number of issues where interparty differences were and remain negligible, such as war and peace, relations with the Palestinians, and the recent racist bill that was passed, the “Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People.”

The Center Jockeying for Position

As practiced in the past, the center parties will once again play the kingmaker role in the upcoming parliamentary elections. The key actors in the coalition formation phase following the April elections will be Benny Gantz (Hosen L’Yisrael), Yair Lapid (Yesh Atid), and Moshe Kahlon (Kulanu). Former Chief of Staff Benny Gantz is forecast to win up to 14 seats in the new Knesset, which makes his new party, Hosen L’Yisrael, the second largest bloc in parliament. It is anticipated that both Likud and Labor will court Gantz as a key partner in the governing coalition expected to emerge in April or May.

As the prospective winner on April 9, Likud will face several options if asked by President Reuven Rivlin to form the next Israeli government. The Likud leader would have three options:

- One option is to seek coalition partners among potential national-liberal allies and minimize dependence on the religious right. His choices would include the likes of Gantz (12-14 seats), Lapid (10-13 seats), Kahalon (5-7 seats), Bennett/Shaked (6-9 seats), and Lieberman (5 seats). This “secular” coalition has the potential to give Likud a majority of 65-75 seats in the Knesset.

- A second option would maintain the traditional alliance between Likud and the religious right camp, including the remnants of the Jewish Home (5 seats), Shas (6 seats), United Torah (7 seats), Gesher (6 seats), and the New Right (6-9 seats). That combination could under certain circumstances give Likud the minimum 61 seats it needs to form the next government.

- The third option is the most likely one to be pursued by Likud. It is essentially a blend of the first two options, whereby Likud would pick and choose potential coalition partners from both camps, i.e., the secular and the religious, to maximize the size of its parliamentary majority while simultaneously minimizing the political compromises it must make to secure the participation of some of the small or marginal parties.

Netanyahu’s Prospects as the Longest Serving Prime Minister

Benjamin Netanyahu is not a very popular politician at this juncture in his political career; indeed, according to the News Company poll, “52 percent of Israelis do not want to see Netanyahu carry on to another term.” However, he remains ahead of his next competitor in the polls. According to The Times of Israel, “Only one-third of Israelis, 34% to be precise, want the PM to return to his post after the April ballot, but that’s still well ahead of any other candidate.” All indications, however, point to a Netanyahu victory on April 9, mostly due to a politically marginalized left and a divided center-right coalition. Only one factor stands in the way of Netanyahu surpassing David Ben-Gurion as Israel’s longest serving prime minister: a quick indictment by Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit prior to the elections.

All indications point to a Netanyahu victory on April 9, mostly due to a politically marginalized left and a divided center-right coalition.

Netanyahu and his Likud colleagues were aware of this possibility before opting for early elections. Their strategy over the past few weeks has been to intimidate the attorney general to prevent him from issuing his decision before or during the elections. According to the Jerusalem Post, “Netanyahu said in a personal conversation that even if an indictment is brought against him during the elections, he’s not going anywhere, and the trial will be held during his term as prime minister.” To be sure, Netanyahu has always been Israel’s ultimate political gambler and once again, he is placing his shaky political future in the hands of the Israeli electorate, which he has manipulated repeatedly and quite successfully in the past. In the final analysis, however, Netanyahu’s fate lies in the hands of the attorney general who will personally decide whether and when to indict him.

1 Source is in Hebrew.

2 Photo credit: Flickr/Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung