The passage of the September 25, 2017 referendum of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) on the independence of Iraqi Kurdistan has garnered much opposition inside Iraq, around the Arab region, in Turkey and Iran, and internationally. While Kurdish independence in northern Iraq or any other area where Kurds reside may not appear imminent, the referendum is clearly a harbinger of serious developments that will involve the Kurds and a number of countries around Iraq in the future.

In order to gain a general understanding of the referendum and responses to it from Iraq, the region, and the international community, Arab Center Washington DC (ACW) has asked its analysts a set of questions about specific countries’ stances on the issue, reasons behind those positions, and potential implications of the referendum’s passage. The following answers are a summary of their opinions, arranged in alphabetical order.

What can Turkey do, other than what it has already done, to deal with the implications of Iraqi Kurdistan’s approval of the independence referendum?

Mustafa Gurbuz, ACW Nonresident Analyst

Turkey had a long list of threats to use against the Kurds, from a complete economic embargo to military invasion; however, only a handful of measures have been taken against the KRG. Given that Ankara would like to punish the Kurdish authorities to get an upper hand in negotiations over Iraqi Kirkuk’s future, it is reasonable to expect the Turkish government to freeze the oil flow from Kirkuk or transfer custodianship rights over KRG oil to Baghdad for a temporary period. For a few weeks, Turkey may even go further and close the Habur border crossing with the KRG until a deal can be reached with its leadership. Yet, in the long run, Turkey would not punish the KRG financially since that would become harmful at home. Iraqi Kurdistan is Turkey’s third largest export market with an annual trade volume of $8 billion; it is also the second largest employer of Turkish contractors, with projects worth about $5 billion annually. Closing the Habur border crossing may have a crippling effect on the economy of Turkey’s Kurdish population in the southeast region. Such an outcome would hurt President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development party (AKP) vis-à-vis the pro-Kurdish parties. Despite playing the Turkish nationalism card for the upcoming 2019 elections—which will usher in Turkey’s new presidential system—Erdoğan would never risk losing millions of Kurdish conservative votes for his party.

Another factor that limits Turkey’s options are strategic realities. Weakening KRG President Masoud Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) would empower the Kurdish opposition parties that would prefer Iran over Turkey as a regional partner. More importantly, the KDP is the only Kurdish regional challenger to Turkey’s nemesis, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Competition between the two groups goes back to the 1990s when they engaged in open armed conflict. Thus, Turkey’s punishment of the KDP would only expand the PKK’s influence in Iraqi Kurdistan, especially in the Sinjar area where the KDP-PKK rivalry is at its peak. Although PKK leaders initially expressed their dislike for Barzani’s referendum idea, they chose to remain silent about it—they were even reluctantly supportive of it—when Ankara’s reaction to the KRG became increasingly negative. The PKK may also extend its influence in Turkey’s restive southeast if Erdoğan takes extreme measures against the KRG, portraying such steps as an all-out war on all Kurds.

What are the important reasons for Iran’s objection to the Iraqi Kurds’ referendum?

Imad K. Harb, ACW Director of Research and Analysis

It is hard to see how Iranian leaders can justify any Kurdish moves toward independence, in Iraq or elsewhere, without betraying their own nationalistic ethos and deep belief in the inviolability of their Islamic Republic. Iran even has its own experience with Kurdish separatism, when the Soviet Union helped establish a Kurdish state in Mahabad following the Second World War. It lasted for only a year and ended with Moscow’s abandonment and a brutal campaign of repression by Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. Both the shah and post-revolutionary leaders conducted ruthless operations against Kurdish nationalists and pursued and assassinated them abroad. While countries see the weakening of neighbors as a good geostrategic policy, Iran sees the Iraqi Kurds’ referendum move not as weakening a historical rival—Iraq—but as preparing the ground for a pan-Kurdish independent state that would also come at Iran’s expense. To Tehran, Kurdish secession in northeastern Iraq will lead to instability in its own northwest and, later, the region’s separation from the country. Further, the KRG’s referendum is seen as but a precursor of a much wider project that aims to unify all Kurds in a nation-state at the expense of other nation-states in the region, Iran included.

What may have surprised Iranian leaders is the decision by political forces in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq—the Gorran Movement and the Islamists—to participate in the referendum after they had declared their opposition to the move. Kurdish leaders in that part of Iraqi Kurdistan are on very good terms with Tehran and had previously formed a balancing faction against Masoud Barzani, the president of the KRG. Their late decision to participate provoked fears in Tehran that it may no longer be able to count on its friends in Kurdistan and may indeed have lost its foothold in that part of Iraq, most likely in favor of Israel, which has supported Kurdish independence. There actually is no escaping the fact that Kurds in all the countries in which they reside have a desire to enjoy a degree of autonomy, a notion that makes Iranian leaders anxious as to when or how their own Kurdish community may feel empowered enough to challenge the central government’s objection to any form of Kurdish separatism. Already, the Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK) is active militarily against security forces and is supported by the PKK of Abdullah Ocalan, leader of the main power behind Kurdish nationalism at this time.

Why was Israel seemingly the only country to encourage the Kurds to hold a referendum on their independence from Iraq? What purpose could that serve?

Khalil Jahshan, ACW Executive Director

This important question has a twofold answer. The first is historical—i.e., pertaining to the old relationship between Jews and Kurds in Iraq. The second is political, stemming from the Machiavellian Zionist perspective on the status of minorities in the Arab world, including Kurds, Maronites, Shi’a, Copts, and others.

1. The waving last week of Israeli flags on the streets of Irbil was not a total surprise. Relations between Kurds and Jews predate the birth of the State of Israel in 1948. The tribal relationship between Iraqi Jews and some Kurds in Kurdistan during the early part of the 20th century was generally harmonious, particularly with the Barzani family. This bond served as a foundation for the emerging friendly relations with Israel in the 1960s and 1970s as most Iraqi Jews gradually emigrated to Israel. The State of Israel, supported by world Jewry, extended political and military support and advisors to the Peshmerga throughout their struggle for self-determination. The friendship was mutual as Masoud Barzani declared in 2005 in an interview with the Arabic Al-Hayat newspaper that it would not be a crime if there were relations between the Kurds and Israel since there are many Arab countries that do.

2. Indeed, the Zionist movement has, since its inception, favored dividing the Middle East into smaller ethnic or religious states to justify the establishment of Israel as a state for the Jewish people. First Israeli Prime Minister Ben Gurion and other Israeli leaders favored, for example, a separate Maronite state in Lebanon. For similar reasons, Israel has always endorsed an independent state in Iraqi Kurdistan. Such states weakened the potential of a strong and united Arab front to challenge Israel’s existence and regional hegemony. Benjamin Netanyahu expressed his support for Kurdish statehood in 2014 by describing the Kurds as a “fighting people that have proven political commitment and proven moderation, and they’re also worthy of their own political independence.” Ironically, he did not apply the same logic to the dispossessed Palestinians next door.

Israel might look awkward being the only country openly supporting Kurdish independence, but, according to Anshel Pfeffer of Haaretz, “Israel isn’t doing the Kurds any favors.” The Netanyahu government is in fact serving its own interests by legitimizing its own existence as a “Jewish state” and poking Tehran and Ankara in the eye by “creating a situation in which Iran and Turkey will find independence that much harder to stomach.”

How best can the United States deal with Iraq’s Kurds now that they have passed a referendum on independence that Washington opposed?

Joe Macaron, ACW Resident Analyst

Since the 1991 Gulf War, US intervention in Iraq has caused a chain reaction that emboldened Kurdish national aspirations. Most notable was the American-led invasion in 2003, which allowed the emergence of an autonomous Kurdistan region. For 14 years now, the United States has danced around that critical issue in a balancing act between the Iraqi central government and the KRG. The US approach to the September 25 referendum was no different. The stance of the administration of President Donald Trump on the referendum has evolved in the past two weeks, from “not support” to “not recognize,” while US efforts to mediate between Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi and KRG President Masoud Barzani have failed so far, both before and after holding the referendum.

The concerns in Washington are that the ongoing crisis is becoming a distraction from the final stretch of the war against the so-called Islamic State (IS) and will hinder efforts to stabilize the recently liberated areas. Presently, the US approach provides a public message of delegitimizing the referendum and reiterating Iraq’s territorial unity, while rejecting any measures that could isolate or threaten Iraqi Kurdistan. However, there is no weight behind that approach if the US president does not become personally involved by conveying a clear view on where Washington stands. Since the Trump Administration might not have the capacity to prevent the crisis from escalating, it has no option but to utilize all available diplomatic tools to convince both Abadi and Barzani to negotiate without preconditions. If the situation further escalates, Washington might have to take sides, which risks further weakening its influence across Iraq and the region. The US Administration has the right approach, yet the referendum crisis should be higher on the president’s priorities and should be integrated into US calculations as the White House shapes its Middle East policy.

What generally has been the position of the international community regarding the Iraqi Kurdish referendum for independence, and why?

Marcus Montgomery, ACW Junior Analyst

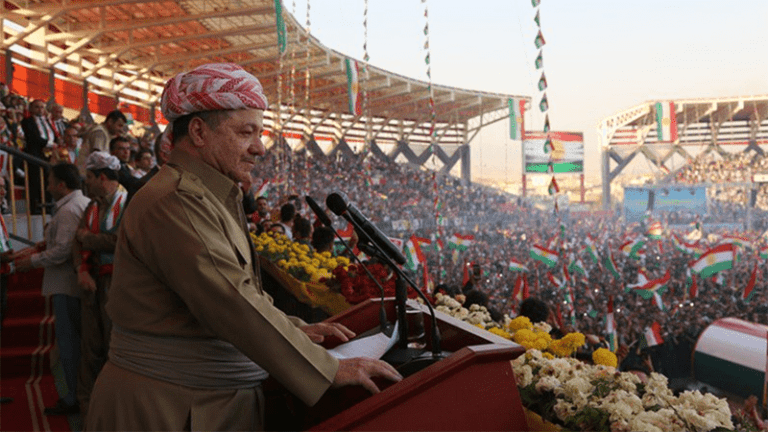

Rarely does the international community agree on anything, but the world’s major powers were united in their opposition to the recent Kurdish referendum on independence. Israel aside, every major nation and multi-state organization urged Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani to forego the independence vote and, when he carried forth anyway, they denounced the effort. Although united in opposition, the reasons each country holds vary greatly.

For the United States, its allies in the European Union—namely Germany, France, and the United Kingdom—and the United Nations, the major fear of destabilization in the already volatile Middle East is the driving force behind their opposition to the vote. Kurdish forces in both Iraq and Syria have been instrumental in combatting the Islamic State, and the US-led anti-IS coalition fears that Iraq’s response to Kurdistan’s vote could disrupt the progress being made against the terrorist group. Additionally, there are concerns about the stability of Iraq moving forward. While there is some worry about a violent clash between Baghdad and Irbil, western powers are primarily concerned about the political survival of Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, favored by the United States, who is eyeing national elections in 2018. Observers of Iraqi politics say that his electoral success would be greatly diminished if his record against IS is offset by the secession of roughly one third of the country.

On the other hand, countries like Russia, China, Iran, Turkey, and the states that make up the Arab League are concerned with other side effects of the referendum. It is disingenuous to say these countries do not fear the disruption of anti-IS efforts, because they certainly do. But many of these demographically diverse states are more worried about the rise of nationalist separatist movements. Turkey and Iran—with their large and often restive Kurdish populations—have legitimate reasons to oppose the creation of an independent Kurdistan on their borders. But, Russia, China, and Arab League member states like Morocco and Bahrain also have populations that could use the Iraqi Kurds’ efforts as inspiration for seeking their own greater autonomy or political power.

What are some important complications from a Kurdish referendum on independence from Iraq?

Abdulwahab Al-Qassab, ACW Visiting Scholar

There are intra-Kurdish, domestic Iraqi, regional, and international implications to the referendum on independence. The Kurds cannot really claim to be unified about the issue. The Sulaymaniyah bloc, which decided to participate in the poll only one day before it was held, cannot be assumed to always support Barzani because of disputes over his corruption, monopolization of power, illegitimacy, and subversion of the Kurdish constitution. But what is really serious is the response of the central government, which rightly considers Kurdistan to be an integral part of Iraq and rejects any separatism. Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has in no uncertain terms ordered the KRG government to surrender control over the Irbil and Sulaymaniyah airports, which will cut the region off from the rest of the world. The government has also cooperated with the Turkish and Iranian governments to close their border crossings with Iraqi Kurdistan and have issued orders for the cessation of all oil exports from there.

There also is a serious problem with how the disputed territories under the military control of the KRG, through the Kurdish Peshmerga, will be handled. Different ethnic communities live in those areas (Arabs, Turkmens, Yazidis, Christians, Assyrians) and they have not approved the referendum. Additionally, the Iraqi constitution, which the Kurds were instrumental in writing and approving, contains no provisions for conducting secession referenda and prohibits separatism. What this points to is a certainty of armed conflict to dissuade the Kurds from secession, a situation whose outcome no one can predict. On the other hand, it is hard to imagine that any regional neighbor will approve Kurdish separatism—certainly not Turkey or Iran. Neither is there any reason to think that the international community is going to oppose the Iraqi government in its demand to ignore the referendum’s result. The UN Security Council actually voted unanimously to reject the referendum. What indeed is required now is a return to reasonable thinking about how best to maintain Iraq’s unity and territorial integrity so that the country can deal with the numerous political and economic problems it faces.

The Syrian Kurds have already taken steps for autonomy in Syria. How does the passage of the referendum in Iraqi Kurdistan help them?

Radwan Ziadeh, ACW Senior Analyst

While many Syrian Kurds may look positively on the results of Iraqi Kurdistan’s referendum, they may not enthusiastically seek to conduct a similar poll for independence from Syria. The main reason for that are intra-Kurdish political dynamics that have been on display since the start of the Syrian war in 2011. More specifically, there are ongoing rivalries between the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the Kurdish National Council (KNC). The PYD has close relations with the PKK––whose leader, Abdullah Ocalan, is imprisoned in Turkey—and holds wide sway over Kurdish areas, while the KNC includes numerous smaller parties that have close ties to Masoud Barzani but lacks the decisive military power on the ground. The PYD’s influence in northern and northeastern Syria is commensurate with the strength of the Kurdish Protection Units (YPG)––the main force within the Syrian Democratic Forces––which has been able to anoint itself the main Kurdish fighting force on the ground. Needless to say, Ocalan and Barzani stand on opposite sides of Kurdish politics.

While the KNC has welcomed the Iraqi Kurdish referendum and its results because of its relationship with Barzani, the PYD has been more circumspect about it—although it declared that it will defend the Kurds wherever they lived against Turkish and Iranian threats. It is noteworthy also that the PYD, aided by the YPG, conducted its own “referendum,” on the same day as that of the Iraqi Kurds, to approve the establishment of a so-called “Rojava [Western Kurdistan] Legislative Council,” which would govern the three Syrian Kurdish areas of al-Jazeera, Euphrates, and Afrin within a “federated Syria.” Indeed, while the PYD is following in the footsteps of Iraq’s KRG and hopes to have autonomy for now for the Syrian Kurds, the conflictual nature of the Ocalan-Barzani relationship makes it difficult for the two leaders to seek a joint project on pan-Kurdish independence. That is why Syria’s Kurds will hold off for the time being on seeking independence from a unified Syria.