The battle by the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) and their allies to retake control of the city of Mosul, while bloody and drawn out, now appears to be in its final phases. The central government is turning toward plans for mop-up operations in other areas still suffering from the presence of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

But beyond the question of Mosul and what follows in the immediate aftermath, more important issues still shadow the future of Iraq. These revolve around the same three unanswered questions that have vexed Iraqi leaders since 2003.

- First is the question of Iraqi national identity. Can the Shi’a leadership govern in a way that promotes consensus and acknowledges and accommodates the aspirations of Iraq’s ethnic and religious minorities?

- Second, can the Sunnis accept their minority status and work within the system to achieve political goals, rejecting the politics of entitlement, grievance, and violence?

- Third, can the Kurds accommodate their desire for greater autonomy within Iraq itself, maintaining strong influence in the capital while acknowledging that Baghdad has a legitimate and necessary role to play in the north?

All these pressing issues have been pushed into the background by the need for a semblance of unity and national purpose in the face of the ISIL challenge. Nevertheless, they are as difficult and vital as ever, 14 years after the invasion that overthrew the Saddam regime. After ISIL, the future stability of Iraq as a unitary state depends on the answers.

State of Disunion

Iraq’s political class has yet to break decisively with the politics of ethnicity and sect, which has plagued the country for nearly a decade and a half. Following a comparatively hopeful electoral cycle in the 2010 national elections, for which a number of electoral slates were formed across ethnic and ideological lines, Iraq’s politicians quickly relapsed into zero-sum politics and sectarian agendas. Currently, the internal political situation is little changed. No plausible strategy for “national reconciliation” among competing groups has been articulated, let alone implemented. Political infighting has made legislative progress on most key issues nearly impossible, and it heavily constrains Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s freedom of action.

Gridlock has been intensified by the run-up to national elections next spring; competing factions and personalities have little incentive to hand legislative victories to the prime minister or one another as they seek to advance their own political prospects. The prime minister, while favored for a second term by majorities in the southern and central governorates because of his successes against ISIL, faces challenges from former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, who is forming an electoral slate in anticipation of running for a third term, and potentially Iyad Allawi, another former prime minister. Thus, Iraq risks wasting another important opportunity for progress at a time when “[ISIL is] on the ropes, people [are] tired of fighting, and the economy [is] propped up by external assistance.” Yet many among Iraq’s key communities and power centers are looking ahead—to the next fight.

Sunnis and Kurds Making Their Calculations…

Among Iraq’s Sunnis, the situation remains unsettled. Riven by years of war and insurrection, the Sunni heartland—centered in Anbar, Ninevah, and Salaheddin provinces—is economically depressed and politically unstable. As many as six million of Iraq’s Sunnis have been internally displaced or rendered homeless in the struggle with ISIL since 2014. Much of the infrastructure remains in ruins, with little in the way of reconstruction assistance and humanitarian aid from Baghdad. Many Sunnis remain suspicious of and disaffected with the government, which is seen at best as unresponsive and incompetent, and at worst as a hostile foreign occupier kept in power by Iran and the Shi’a militias.

The question for many Sunnis, then, is how—if at all—to reset their relationship with the center after a devastating period of displacement, destruction and political disenfranchisement. Experiments in backing Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) in 2005 and ISIL in 2014 as a counterweight to the Baghdad government went badly awry. The likelihood of external support from the Sunni states of the Gulf for another round of armed resistance to the government is low. Internal political divisions among Iraq’s Sunnis remain significant. All these factors tightly limit the Sunni community’s options in its dealings with Baghdad. Sunni leaders will be under pressure to cut the best political deal they can and secure massive amounts of reconstruction aid, without appearing to knuckle under to Shi’a political leaders. This has proved an all-but-impossible task in the past.

The Kurds, too, will have choices to make after ISIL is defeated. Having played a critical role in stemming the Islamic State’s advance, the Kurds could choose to parlay that role into a better political-economic deal with Baghdad. However, at present the Kurds appear to have other ideas. As one senior Kurdish advisor said privately during a recent visit to Washington, negotiations with Baghdad to set the terms for eventual Kurdish independence are possible; the government’s feckless initial response to the ISIL invasion, and its persistent inability to manage a true national dialogue to achieve lasting solutions to bitter territorial, economic, and confessional issues, have intensified the desire of large majorities of Kurds to break away from Baghdad altogether.

The Kurdish Regional Government’s (KRG) two principal political parties, the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), announced plans in April for a referendum on independence later on in the year. As one KDP parliamentarian told Iraqi News, the Kurds have lost hope for the possibility of coexistence within a unitary Iraqi state, and that the referendum will result in a vote for independence. During the ISIL conflict the Kurds have vastly increased the amount of Iraqi territory under their control; the raising in April of the Kurdish flag over the city of Kirkuk, in a region that controls approximately four percent of the world’s known petroleum reserves, has intensified concern that the Kurds will lay claim to these territories as part of an independent state, or use them as a powerful bargaining chip for concessions from the central government.

Here the Kurds appear to glimpse an opening with the Trump Administration, which is well-disposed to the Kurds given their close cooperation with the US military and their effective role in the battle against ISIL in northern Iraq. The administration appears open at the very least to closer ties with the KRG and potentially to brokering a deal between Turkey and the Kurds. Whether Trump’s enthusiasm for the Kurds will translate into support for Kurdish independence in Iraq’s north is unclear (although many Kurdish politicians and analysts think so), but the administration appears willing to consider the possibility.

…And So Do Militias and Other Armed Groups

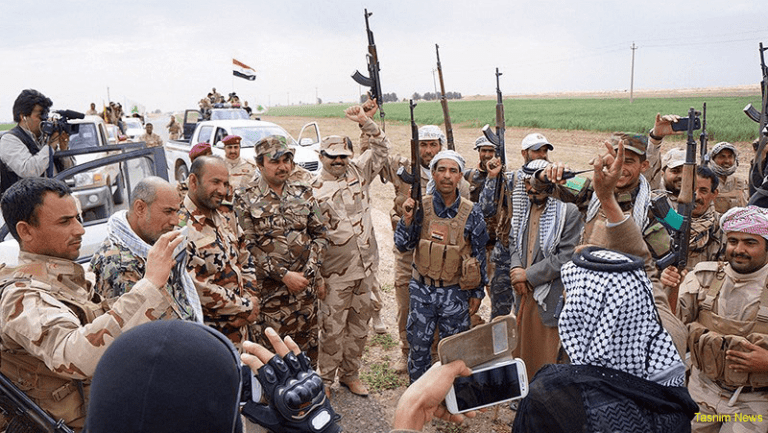

Complicating the political scene and security situation is the influence of the powerful Shi’a militias that Baghdad has depended on for years in its efforts to control the country, but particularly in the last two years as it has fought to overcome ISIL. Today’s iteration, the largely Shi’a Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF, or al-Hashd al-Sha’bi in Arabic) have been instrumental in assisting the Iraqi Security Forces in the fight.

The PMF recently has been brought under the Iraqi government’s legal control by the country’s new militia law. However, many of these units are directly backed by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Quds Force; there are fears that Tehran may seek to transform the PMF into a Lebanese Hezbollah-style state-within-a-state. With Iran’s collusion, the PMF will likely seek to consolidate their influence by leveraging their military gains—possibly by pushing back against renewed Kurdish assertiveness in Mosul and elsewhere. In addition, PMF leader Hadi al-Ameri is reported to be considering forming his own political bloc in anticipation of next year’s elections.

Tribal forces and criminal gangs are also challenging the government and the rule of law. By many reports, Baghdad has lost control over key portions of the country, including Basra and other parts of the south. These groups will spare no effort to maintain their lucrative spheres of control.

Abadi’s Choices: From Difficult to Impossible

Given this fraught situation, Abadi faces several key challenges that will loom large in the immediate aftermath of Mosul.

First, the prime minister can work closely with international donors to develop credible plans for the reconstruction of Mosul and other areas badly hit in the war against ISIL and for addressing the massive humanitarian crisis it spawned. This will be the government’s key test of credibility and competence, not to mention the extent of Abadi’s political capital.

Second, Abadi needs to pursue some sort of national reconciliation process, an effort to which he appears committed. This will be complicated by Sunni suspicions of the Shi’a-dominated central government as well as Kurdish maximalism. The unwillingness of many in the Shi’a political class to support meaningful concessions to the Sunnis and Kurds constitutes a major roadblock, too.

Third, Abadi would do well to forge ahead with his plans to combat official corruption, an intractable problem that he took on after his selection as prime minister in 2014. Corruption has been a drag on economic development and a major source of disenchantment with government, and must be addressed effectively if Iraq is to advance. But the effort has largely foundered in the last few years, despite well-crafted plans for different sectors developed by various government agencies.

Fourth, the prime minister can redouble his efforts to improve Iraq’s economy. Relatively high current levels of foreign assistance will help, but low oil prices and historic underinvestment in vital infrastructure create formidable obstacles to sustained economic improvement.

Fifth, it would behoove Abadi to continue the process of incorporating militias into the ISF within a clear chain of command, and/or divert their manpower into government-directed projects such as public works. He cannot make the mistake Maliki did by promising to employ and pay these forces (in Maliki’s case, the anti-AQI Sons of Iraq) and failing to follow through. Abadi must also consider how best to deploy the ISF to reestablish order in lawless areas. Progress here will go a long way toward rebuilding the trust of the Sunnis and enhancing Abadi’s electoral prospects.

Finally, he can look for opportunities to effectively leverage the positive relationship with the United States to bolster security and stability. During his visit to Washington in March, Abadi discussed with Trump the possibility of building on the Strategic Framework Agreement (SFA) both countries signed in 2008, which set the terms for a broad range of military and civil cooperation. Moreover, he needs to decide on the future role of the US military in Iraq, including the possibility of a substantial leave-behind force after the current campaign in Mosul concludes. Negotiations are reportedly ongoing between Washington and Baghdad on this subject, despite denials from Abadi.

The question of an American troop presence is controversial, and some leaders of the PMF and the Sadrist movement have ruled it out. However, it would be welcomed by the Kurds and many Sunnis, who would view such a presence as a sign of America’s commitment to a stable Iraq and as a political check on the Baghdad government’s power. While denying that US “combat troops” will stay on, the prime minister seems to be trying to finesse the issue by saying some US troops will remain, but only in a role of providing “training, logistical support and intelligence cooperation and gathering.” Since all US troops (approximately 7-8,000) are currently considered “advisors” to avoid triggering a requirement for parliamentary approval of a foreign combat troop presence, Abadi’s formulation may be designed as a palatable cover story for the troops’ real mission.

Role of the United States Going Forward: Options for US Policy

So far, despite Abadi’s cordial visit to Washington and talk of continued military cooperation, there has been little indication that the administration is planning to ramp up its engagement in Iraq. There has been virtually no public discussion of any US plan to engage actively in repairing the country’s political divisions after the reconquest of Mosul, or of a strategy to actively support Iraq’s stability and security. The United States appears willing to help organize and partially contribute to the initial reconstruction and humanitarian effort, but has indicated it will remain focused primarily on the continuing counterterrorism effort. “As a coalition, we are not in the business of nation-building or reconstruction,” Tillerson told a meeting of the global anti-ISIL coalition in Washington in March.

The United States would do well to consider being a main actor in Iraq once more. The administration has a powerful motive—helping to restore regional stability, forestall a resurgence of ISIL, and blunt Iranian influence—as well as the political capital to do so, stemming from the military and logistical support the United States has committed to Iraq. This influence, however, is a wasting asset that will be squandered unless Washington acts to use it.

The United States needs to consider several policy options, which largely mirror those of Abadi, as follows:

- Reach an agreement with the Iraqi government on leave-behind troop levels sufficient to carry out an expanded train-and-equip mission, and provide robust logistical and intelligence assistance and air and troop support as necessary. While it is preferable to structure such support as a “non-combat” mission to avoid a possible “no” vote by Iraq’s Council of Representatives, the United States is advised to negotiate a Status of Forces Agreement sufficient to provide a firm legal and diplomatic basis for the mission.

- Work to assemble the resources necessary for the reconstruction of Mosul and the Sunni heartland, with a special emphasis on resettling Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). This can done within the framework of the global anti-ISIL coalition. The United States should also assist Iraqis to develop detailed political and security arrangements for Mosul following the ouster of ISIL, and serve as the principal intermediary to deconflict Kurdish and ISF units in disputed areas, as it has in the past.

- Engage with Abadi on using the Strategic Framework Agreement, signed by Iraq and the United States in 2008, to establish wider and deeper bilateral relations.

Over the longer term, the United States could also help Iraq develop a political compact to manage the divisions stemming from the 2003 invasion. This must include practical discussion of the devolution of central powers to the governorates—some form of federalism, in other words, as provided for in Iraq’s constitution—and working arrangements on equitable control over and distribution of national resources, principally petroleum revenues, but also central government budget support to the governorates. National reconciliation has proved a highly elusive goal in Iraq, and the levels of mistrust, bad blood, and turbulent politics will make the task that much harder. Still, an American presence at the table has been instrumental in getting the parties to work together, however grudgingly, on many issues.

Dangers of American Inaction

The administration must avoid the tendency to define its mission in Iraq narrowly and simply react to events. The temptation to do so may be overwhelming once the Mosul fight is finished and Iraq has slipped once again from US headlines. The administration may be more than happy to let Iraq go its own way as long as Iraqi claims on American military, diplomatic, and financial resources are held to a minimum.

But inattention risks leaving Iraq wide open to the machinations of its neighbors, especially Iran, which will be looking to capitalize on the defeat of ISIL to cement its own influence in the country, in particular through the agency of the militias Tehran supports. Iraqi actors themselves, once united in the fight against ISIL, will scramble to advance their own interests by any means possible, including violence. This will further fracture Iraqi society and politics and pose heightened risks to Iraq’s stability, especially from remnants of ISIL and future extremist groups that will try to take advantage of the chaos. A renewed American commitment to Iraq, in concert with responsible Iraqi parties, is critical to encouraging a better outcome.