In late July 2025, large-scale protests against electricity outages, economic deterioration, and general mismanagement by Yemen’s Internationally Recognized Government (IRG) erupted in Mukalla, Yemen’s fifth-largest city and capital of the eastern Hadramawt governorate. Although outside attention on Yemen typically focuses on the actions of the Houthi movement, rather than on other internal dynamics, such demonstrations are not uncommon. As often happens in IRG-held areas, fuel deliveries from Yemen’s hydrocarbon-rich interior to power stations in Mukalla were disrupted (in this case because suppliers restricted diesel deliveries due to unpaid debts from the local government), resulting in extended power blackouts. Angry protesters blocked traffic, including fuel trucks, on major roads around Mukalla until the IRG addressed their demands for improved governance.

While the protests died down by mid-August without any gains amid a mix of repression and improved economic conditions, the unrest is the latest example of how various actors in IRG-held areas disrupt hydrocarbon flows in order to gain leverage against the authorities, and of the IRG’s structural weakness in its ongoing civil war against Yemen’s Houthi movement. Plagued by political and military divisions, the IRG is unable to ensure the smooth flow of hydrocarbons within the territory under its control. The IRG is also unable to export oil outside Yemen due to the Houthi blockade on its oil terminals in place since 2022, a situation that has starved the IRG of funds. As a result, the IRG is forced to devote significant efforts to managing crises caused by blocked energy supplies, instead of meaningfully challenging Houthi power.

This dynamic has hindered the IRG’s ability to counter the Houthis and to create the conditions for a sustainable end to the Yemen conflict. International airstrikes such as the August 28, 2025, Israeli attack that killed the head of the Houthi-aligned government in the capital Sanaa have done little to impede the movement also known as Ansar Allah. A viable IRG is needed for leverage over the Houthis—and for a viable IRG, Yemen’s hydrocarbons need to flow.

The Internationally Recognized Government and Yemen’s Hydrocarbons

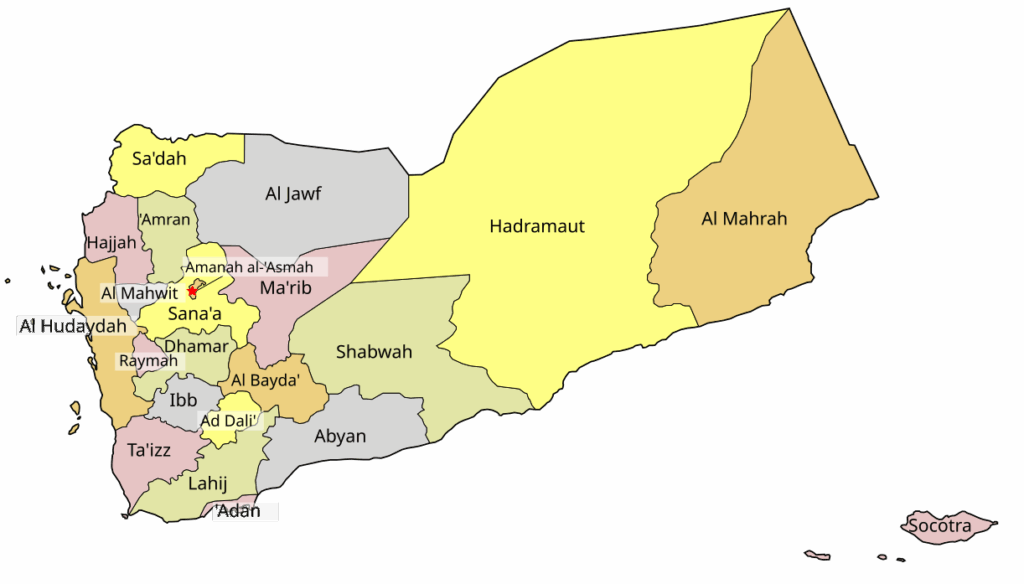

The interiors of three IRG-held governorates located along the border of the formerly separate countries of North and South Yemen are home to all of Yemen’s hydrocarbon resources. In the east is Hadramawt, a southern governorate that produces the majority of Yemen’s oil; to the west is Marib, a northern governorate that has less oil but produces all of Yemen’s natural gas; and in the center is Shabwah, a southern governorate that produces still less oil but contains many of the pipelines, terminals, and ports that handle Yemen’s oil and gas exports. Since their discovery in the 1980s, hydrocarbons have accounted for the large majority of Yemen’s exports and some 70-80 percent of its government revenues. The country’s oil wealth, however, has been unequally distributed, with the three oil-rich governorates historically receiving little direct benefit while well-connected elites have siphoned off much of the revenue. As a result, ordinary Yemenis have seen scant improvement in their daily lives despite the country’s resource base.

A map of Yemen divided by governorate, with Marib, Shabwah, and Hadramawt located in the center and east of the country. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In a context of such inequality, Yemenis have come to recognize the value in targeting the hydrocarbon infrastructure to obtain concessions, with locals in Marib, Shabwah, and Hadramawt having blown up pipelines and blockaded oil fields to pressure the government for decades. The civil war between the IRG and Houthis, which began in 2014 when the Houthis took over Sanaa by force, exacerbated this tendency. Officially the successor to Yemen’s pre-2014 government, the IRG is a fractious coalition of anti-Houthi factions led since 2022 by the eight-member Saudi- and Emirati-backed Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), which is headed by Saudi ally Rashad al-Alimi. The PLC includes representatives of the United Arab Emirates (UAE)-backed Southern Transitional Council and National Resistance Forces, in addition to the Saudi-backed Islamist Islah Party. The IRG was forced to relinquish control of much of Yemen’s government infrastructure when it fled Houthi-controlled Sanaa for the southern city of Aden in 2015, where it is now based. IRG control on the ground in Yemen is only loosely exercised through its various factions and their associated armed groups, who often spend as much time fighting one another as they do the Houthis.

The division of Yemen between Houthi control (green) and IRG-aligned factions including the IRG itself, UAE-backed groups, and affiliated non-state armed groups, including the Southern Transitional Council (yellow), the National Resistance Forces (blue), and the Hadrami Elite Forces (gold). Source: Wikimedia Commons

This lack of centralized authority has forced the IRG to make concessions regarding the management of Yemen’s hydrocarbon resources. While all three hydrocarbon-producing governorates are ostensibly aligned with the IRG, local authorities in Marib, Shabwah, and Hadramawt were able to take advantage of the IRG’s weakness in the late 2010s to negotiate revenue-sharing agreements that provided them a proportion of oil revenues in exchange for permitting exports from their regions. Less officially, the proliferation of non-state armed groups ostensibly aligned with but not controlled by the IRG has led such groups to establish checkpoints throughout IRG-held areas and to impose extralegal levies on fuel transiting through their areas to raise funds for their operations.

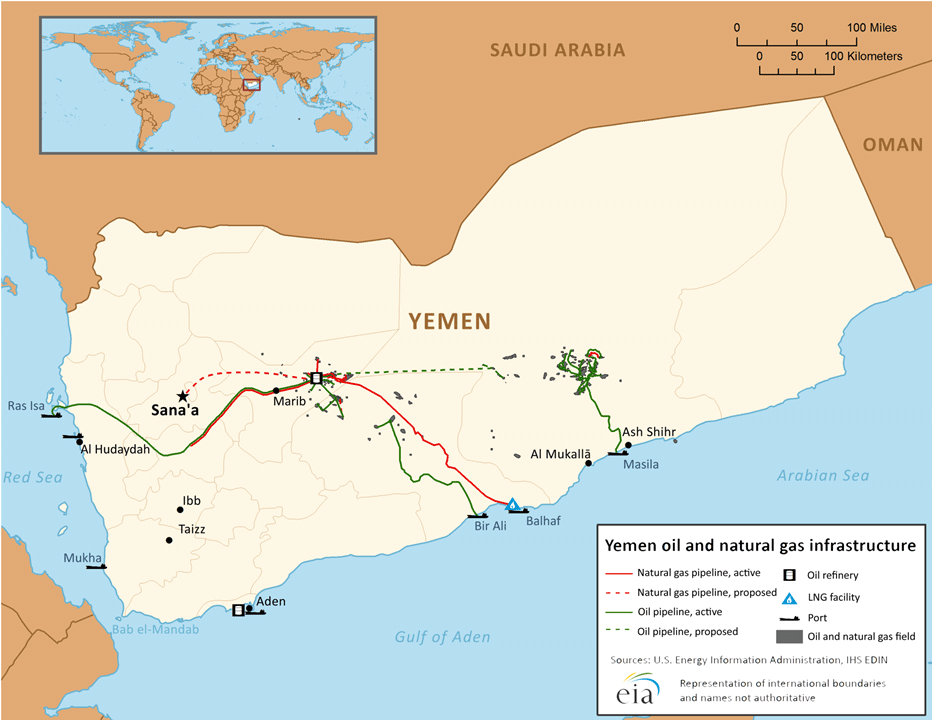

Yemen’s oil and natural gas infrastructure, showing concentrations of hydrocarbon deposits in Marib, Shabwah, and Mukalla. Oil and gas pipelines link these deposits to Yemen’s southern and western coasts. Since early in the Yemen conflict, only the oil pipeline connecting northern Shabwah with Bir Ali and central Hadramawt with Ash Shihr on Yemen’s southern coast have been operational. Source: US Energy Information Administration

The existence of multiple IRG-aligned armed groups in competition with one another has been a recipe for conflict over control of Yemen’s hydrocarbon resources. A separatist group seeking independence for formerly independent South Yemen, the Southern Transitional Council (STC) views the oil resources in Shabwah and Hadramawt as belonging to South Yemenis and has periodically attempted to bring them under its direct control. Since seizing control of Shabwah’s oil fields in clashes with Islah-aligned IRG military units in 2022, the STC’s main goal has been to take oil-rich central Hadramawt. This area remains dominated by Saudi-backed groups including Islah, which supports a united Yemen, and the Hadramawt Tribal Alliance (HTA), which advocates for Hadrami regionalism. Although armed clashes have been kept to a minimum, these disputes have repeatedly interrupted hydrocarbon flows from Hadramawt, where both STC-aligned groups and the HTA have attempted to blockade oil fields to pressure the IRG to take their preferred course of action.

The Houthis and Hydrocarbon Flows

Yemen’s IRG factions are not the only ones aware of the power of blocking energy flows. It is the IRG’s principal rival, the Houthi movement, which has wielded this tactic most effectively. A Zaydi Shia revivalist group that emerged in the 1990s, over the course of two decades of conflict the Houthis have evolved from a fringe insurgency in the mountains of northwest Yemen to the de facto rulers of territory where 70 percent of the Yemeni population lives. The Houthi movement claims that its main goal is to defend Yemen and the broader Middle East region from foreign aggressors like the United States and Israel, but its opponents accuse it of attempting to install a totalitarian theocracy. A member of the Iran-led Axis of Resistance, since October 2023 the Houthis have conducted drone and missile attacks against Israel and international shipping as part of a remote “blockade” to pressure Israel to end its assault on Gaza.

The Houthis’ original blockade, however, targeted the IRG, not Israel. Foiled in their military offensive to seize hydrocarbon-rich Marib from the IRG and attempting to gain leverage in subsequent negotiations, in late 2022 the Houthis began launching drone and missile attacks at international tankers attempting to load oil for export from terminals along Yemen’s IRG-controlled southern coast. Although the Houthi strikes did not directly hit any tankers, the threat of continued attacks alone has been enough to completely suspend the IRG’s international oil exports for the last three years. This situation has financially devastated the IRG, which has lost much of its revenues and has become critically dependent on aid from an increasingly reticent Saudi Arabia. While there is periodic talk at the United Nations of a peace deal that would see oil exports resume in exchange for Houthi-held areas receiving a portion of the revenues, these discussions have been left dead in the water over disagreements about the division of revenues (including STC opposition to South Yemeni oil being used to pay the Houthis) and international opposition to “rewarding” the Houthis for their attacks on Israel and Red Sea shipping.

The Need for a Viable IRG

Since the start of the Houthi oil blockade in 2022, IRG-held areas have experienced something of a financial apocalypse, as the IRG has been unable to reliably pay salaries or to obtain foreign exchange from exports to support the value of the Yemeni currency, the rial. Under these dire conditions, power outages such as those seen in Hadramawt are frequent and have served as a catalyst for protests rooted in simmering discontent against the IRG. Due to the Houthis’ blockage of exports, IRG-held areas produce excess hydrocarbons, but fuel deliveries to cities such as Aden and Mukalla have still been constantly interrupted by a never-ending parade of protest movements, tribes, unions, and militias seeking to disrupt hydrocarbon flows to get their due amid the tumult.

The IRG’s inability to secure hydrocarbon flows is critical to understanding its continued weakness in the Yemen conflict. Lacking the political unity to resolve internal disruptions and the military capabilities to defend itself against the Houthi export blockade, the IRG has in turn been forced to devote much energy to managing the crises created by these disruptions instead of challenging Houthi power. The IRG’s weakness was vividly illustrated in its response to the Operation Rough Rider US bombing campaign against the Houthis that took place during March-May 2025. Despite years of lobbying for US intervention against the Houthis, the IRG was essentially a bystander during the 2025 operation, with analysts dismissing its ability to coordinate a ground campaign to take advantage of the situation.

The IRG’s continued weakness presents a problem for countering Houthi power or bringing about a sustainable end to the Yemen conflict. A decade’s worth of Saudi, US, and Israeli airstrikes against the Houthis have shown they do little to impede or even to influence the movement while causing considerable harm to civilians. In contrast, the two occasions that the Houthis have negotiated substantial ceasefires—the 2018 Stockholm Agreement and the 2022 truce that has halted most Houthi-IRG fighting in Yemen for the past three years—came following their 2018 and 2022 defeats in Hudaydah and Marib respectively by a briefly united IRG. In light of this reality, a stronger and more united IRG is needed to constrain the group. The fiscal viability of the IRG requires unconstrained hydrocarbon flows—and its popular legitimacy depends on using hydrocarbon revenues equitably.

The IRG’s continued weakness presents a problem for countering Houthi power or bringing an end to the Yemen conflict.

As a first step, the United States, Europe, and the Saudi-led coalition supporting the IRG should help its factions reach a durable political settlement that would allow the various IRG-aligned non-state armed groups to be integrated under a single command, permitting the removal of extralegal levies and reducing the chance for intra-IRG armed conflict over Yemen’s oil resources in return for allowing fuel flows. Reaching such a settlement will not be easy—previous attempts to unify UAE-backed, STC-aligned groups have notably failed—but may be feasible with further PLC restructuring. The United States and its allies should also press for an end to the Houthi blockade on IRG oil exports, whether by helping the IRG to develop a plan to counter Houthi attacks, by reaching a settlement with the Houthis that would not overly disadvantage the IRG, or by pursuing both approaches in tandem.

Once the obstacles to hydrocarbon flows are removed, IRG leaders and their international supporters must focus on ensuring that revenues are distributed efficiently, equitably, and accountably. Local communities’ readiness to disrupt hydrocarbon flows reflects their concern that they would otherwise see no benefit from these resources, as well as from their anger over the IRG’s corruption and incompetence. Governments supporting the anti-Houthi coalition, therefore, should increase investment in institution-building and anti-corruption programs in IRG-held areas. In the longer term, allied governments and other donors should facilitate meaningful dialogue among Yemenis on the equitable distribution of the country’s wealth and resources.

Conclusion

After more than a decade pursuing short-term military solutions in Yemen, the international community should now develop a long-term strategy based on a better understanding of Yemen’s politics and economy. Instead of getting caught up in questions of whether Israeli airstrikes can kill enough Houthi leaders to affect the group’s behavior—such attacks deliver mostly symbolic blows—the international community should focus on helping to resolve some of problems that have prevented the IRG from becoming an effective counterweight to the Houthis. While the short-term objective of stopping Houthi attacks on Israel and international shipping would be better served by halting Israel’s genocide in Gaza through a ceasefire—a previous iteration of which completely ended Houthi attacks on shipping and Israel—the long-term solution of building a credible alternative to the Houthi movement must center on restarting hydrocarbon flows and on transforming the IRG into a more viable governing partner.

The views expressed in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

Featured image credit: FB/Yemeni PLC